A little over 70 years ago the third mass execution of inmates in the Solovky special-purpose prison (Rus.: STON) since the beginning of the Great Terror took place on the archipelago in the White Sea. According to decree no. 303 of the special troika of the NKVD Directorate for Leningrad oblast, on Feb. 17, 1938, 198 people were executed. One in five of these prisoners was a native or resident of Ukraine.

UNSOLVED MYSTERY

A total of 1,620 inmates were killed as a result of two earlier punitive operations that were carried out in Karelia in 1937 (between Oct. 27 and Nov. 1-4) and on the territory of Leningrad oblast (Dec. 8). A memorial was established on the site of the first execution in the Sandarmokh ravine near Medvezhegorsk in Karelia. As the Russian researcher Aleksandr Cherkasov has written, the condemned prisoners were “processed” for execution in three barrack rooms. In the first one, a member of Mikhail Matveev’s firing squad brigade “identified” the prisoner, stripped him down to his underwear, and searched him. In the next room the prisoners were tied up. In the last room the bound prisoners were stunned by a blow to the back of the head with a wooden mallet.

Then, 40 prisoners at a time were loaded onto a vehicle and covered with a tarpaulin. Guards sat on top of this pile, which was driven to the Sandarmokh ravine. If some of the unconscious prisoners came to, the brigade members would “calm” them down with a blow of their wooden mallets. On this day in early November it was cold, dark, and desolate at the execution site, located more than a kilometer from the highway. The half-dead people were thrown one by one into large prepared pits. Matveev personally shot each one in the head. This is how 1,111 out of 1,116 Solovky condemned prisoners were killed. Owing to various reasons, four prisoners were sent to other prisons, and one died before the execution.

The possible site of the second mass execution (509 prisoners) — the waste ground of Koirankangas — has not been officially recognized, although searchers from the St. Petersburg branch of the Memorial Society found several pits containing the remains of people who were shot at the Rzhishchev testing ground in Leningrad oblast.

Researchers hope to find the final stopping-place of prisoners who were tortured to death according to decree no. 303 on the Solovetsky Archipelago. They expect to find it there because the White Sea is covered with ice in winter, so it was a problem to convoy 200 people under escort to the Karelian coast. However, the theory of the “island execution” has not been confirmed by any evidence, so the mystery remains unsolved.

Decree no. 303 covers 53 pages of dense typewriting and was signed on Feb. 14, 1938, by the special troika of the NKVD Directorate headed by Mikhail Litvin. Litvin was a Jew born in the Transbaikal region, who had been a Bolshevik since 1917. Despite his lack of education, he was an experienced party apparatchik. In March 1933 he was appointed to head the cadres department of the Central Committee of the Communist Party (Bolsheviks) of Ukraine, and in 1936 he was promoted to the post of second secretary of the Kharkiv oblast committee of the CP(B)U. From October 1936 he headed the cadres department of the NKVD of the Ukrainian SSR. Litvin’s further career advancement led him to the post of head of the 4th (secret- political) department at the GUGB NKVD of the USSR (May 1937), and in January 1938 he became the head of the NKVD Directorate for Leningrad oblast. Within a few months the 46-year-old state security commissar, 3rd rank, would commit suicide by shooting himself.

The same troika included state security Major Vladimir Garin (also known as Ivan Zhebenev), who was born in Kharkiv into a priest’s family. He became a Cheka in 1919. At one time, he served in Podillia together with Leonid Zakovsky (Genrikh Shtubis), later becoming his deputy in the NKVD Directorate for Leningrad oblast. The third member of the troika was the Leningrad oblast prosecutor Boris Pozern (also known as Zapadny, Stepan Zlobin), who was born in Nizhnii Novgorod. He was a party worker and Sergey Kirov’s comrade-in-arms. Pozern was executed by firing squad in 1939 and rehabilitated in 1957.

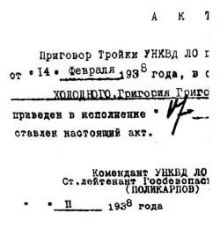

There is no information about the way the execution in Solovky took place. Acts stamped “absolutely secret” would have been signed by state security Senior Lieutenant Aleksandr Polikarpov, the commandant of the oblast NKVD Directorate. But these documents with the name of the “regular executioner” in the letterhead were signed by a higher-ranking person, state security Major Nikolai (Luka) Antonov-Hrytsiuk, who had been dispatched to the White Sea region from Moscow to carry out the sentence in the third prison stockade of the STON convoy. In his time, this former counterintelligence officer with a lengthy term of service (since 1920) had served on the territory of Ukraine: in Kyiv, Konotop, and Kharkiv. In the late 1920s he was transferred to Rostov-on-Don. He was later transferred to Kabardino-Balkari. In 1937 he became the deputy head of the 10th (prison) department of the NKVD of the USSR and its head in July 1938. Antonov-Hrytsiuk was prosecuted and executed in 1939. He was rehabilitated in 1955, during the “Khrushchev thaw.”

WHOM THEY WERE KILLING

What do the yellowed NKVD documents say about our fellow countrymen whose life ended in the White Sea region? The political prisoners sent to the Solovky special-purpose prison camp had been sentenced for counterrevolutionary crimes — “nationalistic, terrorist, insurgent, espionage, sabotage, Trotskyite, wrecking, and fascist activities” — during the Great Terror. To further this goal, this list of crimes fabricated by operative workers of the STON was padded with stereotypical phrases about the “sins” of the condemned: “Maintaining their counter-revolutionary positions, they continue to engage in counterrevolutionary activity among the prisoners.”

An analysis of the lists of condemned indicates that nearly all Ukrainian prisoners arrived in the camps between 1932 and 1936. Every second prisoner’s original death sentence had been commuted to a 10-year term of imprisonment. Every fourth “counterrevolutionary” had a higher education. Some Ukrainian-born prisoners were ethnic Russians, Jews, and Poles. The agronomist Volodymyr Drazhkovych, who was born in Odesa, was registered as a Circassian, the Crimean laborer Heorhii Ionidis was a Greek, and the Evpatoria-born lawyer Zakhar Habai was a Karaim. The Georgian Galaktion Kipiani, who worked as a wine maker at the Shustiv Plant, was arrested in Odesa.

In his memoirs the Solovky inmate Semen Pidhainy mentions a prisoner who was executed in February 1938: “Semen Semko, the former rector of Kyiv University who later headed the Ukrainian Central Archives Directorate, lived in the small monastery of Filiton. We ran into each other as old acquaintances. He immediately said that he was not surprised to see me in Solovky: he said I had been on this path long ago when he was the rector and I was dismissed from the university. But he was thinking about the reasons he was here with me.”

Pidhainy told Semko that he (Semko) was also in Solovky “according to the law” because: “a) he is a Ukrainian; b) a former member of the Ukrainian Socialist Revolutionary Party, who later joined the CP(B)U; c) he did not want to dismiss me from the university and only did it under pressure from the special department; d) he knows of several cases of this kind that took place in the university, and finally, when he was the head of the Ukrainian Main Committee on Methodology and later of the Ukrainian Central Archives he always led a Ukrainian line.”

FOR WHAT CRIMES WAS THE HIGHEST DEGREE OF PUNISHMENT HANDED DOWN?

Ivan Haievsky, a student at Moscow University, who was born in Chernihiv oblast, the scholar and educator Hryhorii Kholodny, and head of a municipal bank in Artemivsk Mykola Zaiets (Zaiats in the NKVD documents) also found themselves in the White Sea region for “Ukrainian-nationalistic” and “espionage-terrorist” activity. The archival investigation case on Zaiets includes reports on his service as an ensign in the Ukrainian Sich Riflemen and membership in the Ukrainian Military Organization (UVO). The information note included in his criminal case states: “He is trying to prove that all the processes underway in the Soviet Union are nonsense and that the government organizes them to its own advantage.” This was grounds for execution by firing squad.

In October 1937 the jailors wrote the following information notes about the workers Fedir Halishchev from the Kharkiv region and Mykhailo Kulytsky from the Odesa region: “Halishchev harbors hostility to the Soviet government. He expresses his terrorist intentions against the leadership of the AUCP(B) and the Soviet government, he speaks about enemies of the people with compassion. He expresses his sabotage intentions to burn down the Solovky prison.” Kulytsky was said to have violated the prison regulations and for “maintaining his views.” Both were sentenced to execution by firing squad.

During his imprisonment in Solovky a peasant from Poltava oblast named Ivan Lushpan, who had participated in the armed defense of the Ukrainian National Republic in the 1920s, “recounted that he joined the collective farm with the goal of corrupting it. He is militantly hostile.” Lushpan was sentenced to execution by firing squad.

A former Petliurite named Kuzma Kozlov, who was a member of a collective farm in Kharkiv oblast, “proved to be an implacable enemy of the Soviet government. He engages in slanderous conversations.” He was sentenced to execution by firing squad.

The Polissian peasant Mykola Kostruba (Kostrub — in some documents) expressed “his malicious hatred of the Soviet government, he does his designated work negligently...he tried to organize a group refusal to work, saying: ‘Let’s not go to work, then they will give us more bread and food.’” He was sentenced to execution by firing squad.

Ihor Hrytsai from Odesa, who was accused of espionage without justification, “expressed his hatred of the Soviet power, discredited the leaders of the AUCP(B) and the Soviet government. To be shot.”

Tymofii Kushnir, a loader from Vinnytsia region who was accused of espionage without justification, “while in Solovky, [he] is engaged in counterrevolutionary activity, he praises life in Romania and curses Soviet laws.” He was sentenced to execution by firing squad.

The worker Fedir Vorobiov from Kharkiv region (a “saboteur” and “wrecker”) “is spreading abominable slander about the leadership of the AUCP(B) among the prisoners.” He was sentenced to execution by firing squad.

Among the other executed prisoners were the lawyer Fedir Averchenko, the government official Oleksandr Babenko, the forester Oleksii Parkhomenko, the peasants Hryhorii Pshenychny, Yakiv Shkidchenko, Andrii Omelian, Oleksandr Dvorakivsky, Maksym Krotsiuk, Semen Kucheruk, Hryhorii Khyrny, Omelian Melezhek, and Fedir Yaremenko. To them and the many other victims of political terror we say: may their memory be eternal!

Yuriy Dmitriev and Vasilii Firsov from Petrozavodsk, as well as Anatolii Razumov from St. Petersburg and Olga Bochkariova from the town of Solovetskoe, have been trying to locate the site of these mass shootings. After arriving on the archipelago (and before that — in Karelia), this reporter had an opportunity to learn about some of the results of their searches. Unfortunately, the findings near the former monastery of Isakovo do not give the researchers any grounds for optimism. The answer to the question of where the butchers hid the bodies of nearly 200 prisoners who were shot on Feb. 17, 1938, has not been found.