After the award ceremony, Mykhailo Guida told the media that he had already sent one of his mentees for rehabilitation to Germany, where he had an artificial limb put on.

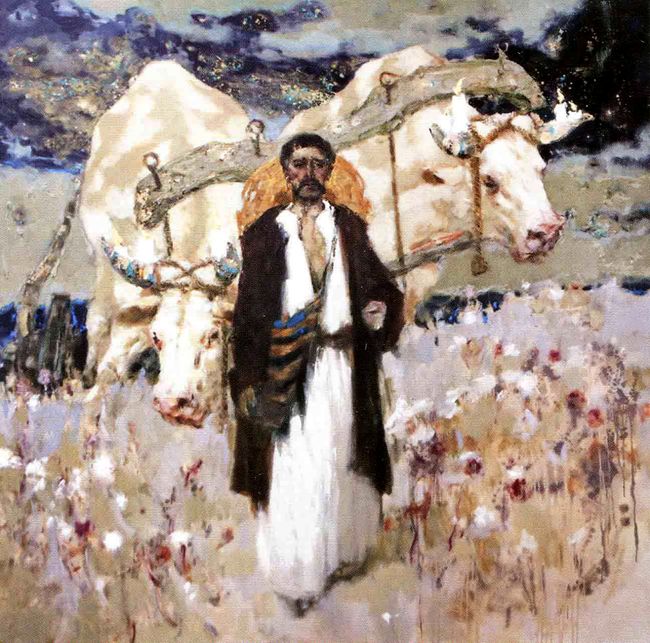

As is known, the artist has won the Shevchenko Prize in the “Fine Arts” nomination. In the opinion of Ukrainian art critics, his painting cycle “In the Same Space” (which comprises such high-profile pictures as Warm Autumn; After the Ball; The Beginning: to Victory!; The Bathing of Horses; The Chumak Road; Serhii Parajanov; Near a Spring Well; and Easter Day) not only have made a considerable contribution to the treasury of contemporary Ukrainian fine arts, but have also gained immense popularity in the countries that know very well and highly appreciate the talented artist’s oeuvre. Incidentally, Guida is one of the first to open up the European, Ukrainian, and Kyivan schools of painting to the Chinese. He, a master of the portrait, is gentle, sensitive, vulnerable, refined, and elegant in every touch of his paintbrush to the canvas.

You were born in Kuban and educated in Kyiv. You teach at the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture. Your surname, Guida, is very colorful. I wonder if you have traced its etymology.

“I am Guida on my father’s side and Chupryna on my mother’s. These are Cossack family lines. My great-grandfather, Demian Doroshenko, headed a local department of education in the Russian Empire times. As an inspector, he supervised Kuban Cossack schools that educated the future elite of the Kuban Cossack Army.

“As for the surname Guida, my colleague Oleksandr Fedoruk, Doctor of Art History, a professor at the Academy’s Department of the Theory and History of Art, helped me clarify its etymology. The name is based on the Turkic word ‘guid’ – a piece of outer menswear that somewhat looks like our zhupan – which spread during the Tatar-Mongol invasion. Interestingly, the surname Guida occurs today not only in the Krasnodar region, but also in Transcarpathia which the Asian nomads reached in the 13th century.”

You graduated from the Kyiv Institute of Art in 1982 and were admitted to the League of Ukrainian Artists a year later. It was a flying start in your artistic career.

“Let me reveal a little secret. The League of Artists wanted to admit me when I was still an art institute student – at least Tetiana Yablonska, the then head of the League’s painting section, suggested that I prepare admission documents. She was surprised that I was still a student who hadn’t yet defended his diploma thesis. Maybe, many people, first of all, artists and art critics, took quite a positive view of my active participation in Ukrainian and USSR exhibitions which displayed some of my first paintings. They marked an original manner of painting and the content of my works. So, I filled the ranks of Artists League members a year after graduation from the Institute of Art.”

THE CHUMAK ROAD

When did you feel a desire to try yourself as easel painting instructor?

“When I was an institute student. I occasionally drew from life in the classroom before classes. My instructor Viktor Shatalin approved this in general, still making some corrections. Then all my classmates began to draw. Besides, I even delivered lectures to younger students at the institute administration’s request, although I was still to receive a professional degree. It is perhaps at that time that I saw that I could combine artistic work and teaching.”

Tell me please about the cycle “In the Same Space.” It comprises heroic-theme pictures, such as Ivan Mazepa Meets Charles XII, Koliivshchyna Rebellion, Haidamakas, and The Beginning. What made you turn to the Ukrainian people’s historical past, when glorious victories were very often accompanied by ignominious defeats?

“Maybe, it is because Cossack blood flows in my veins. These works did not emerge all of a sudden. They were preceded by rather a long preparatory period, when I drew dozens, if not hundreds, of sketches. I gradually saw which expressive means I could use to portray one figure or another.”

AFTER THE BALL

What was your idea of portraying the figure of Ivan Mazepa, for no authentic portraits of this famous Ukrainian hetman have survived?

“When I began to paint the picture Ivan Mazepa Meets Charles XII, I was aware of the fact that the surviving engravings depicted a different person. In all probability, it was a generalized character imagined by previous centuries’ artists. So the spectator can see no other than my idea of this military leader on the canvas. It is my own vision of his image. If you look attentively at the pictures you mentioned, you will notice that they show no details in the attire, interior, and landscape. Instead, there is a certain emotional explosion caused by what you have seen, the statement of a concrete historical event that sealed the people’s fate.”

Your oeuvre comprises a lot of portraits, landscapes, and genre pieces connected with your sojourn in China, where you taught painting at higher educational institutions and staged solo art exhibitions for several years in a row. What made you develop a liking for Orientalism?

“It’s pure chance. It all began with a business trip to China with Anatolii Haidamaka at the invitation of a company. We were to design the interior of a trade house located in China’s free economic area. Later, at the invitation of some higher specialized educational institutions, I taught painting at Zhejiang Pedagogical University and at Hangzhou’s University of Science and Technology.”

I wonder how you adapted to China.

“I’d been interested in the Orient since I was a student. I was keen on Chinese philosophy, particularly the teaching of Confucius, studied the literature, art, and mythology of ancient China. Already a mature artist, I discovered an interesting pattern. Our European painting is three-dimensional, while in China and Japan it is two-dimensional. For this reason, these countries’ painters tried to master the dimension they didn’t know – in other words, to bridge the two continents. Or take, for example, Edouard Manet, Van Gogh, or Gustav Klimt, who brought Oriental motifs to European painting. Therefore, the Chinese art environment was not alien to me – on the contrary, I found comfort in teaching art to students.

“In general, the Chinese have the same scale of values as the ordinary Ukrainian has: family, education, work, material wellbeing, moveable and real estate, health, recreation, etc. But there is also a major difference between them and us. Unlike a Ukrainian, a Chinaman never envies anybody and is content with the little. This may be the result of being brought up in the traditions of thousands-year-old Chinese philosophy. Likewise, a governmental official or a successful entrepreneur will not take the available resources outside his territory to enrich the population of other countries.”

And, finally, many of our art critics spotlight the gallery of prominent Ukrainians you have created in the past few years. It includes the portraits of Les Kurbas, Bohdan Stupka, Serhii Parajanov, Raisa Nedashkivska, et al. What do you think is the most difficult in this genre of visual arts?

“There are different kinds of portraits. For example, the artist can paint a study portrait very fast, for he does this from life. There can also be a life portrait that takes several sessions to paint. And there is also an artistic portrait, a picture-style portrait. In my view, the latter type is the most difficult for an artist. I can’t remember how many portrait sketches of Parajanov I had to make until I finally decided on how to express his image. Everybody notes that I managed to convey his appearance and, what is more, his character in the portrait. To tell the truth, I always paint portraits from memory, not from life. This helps avoid any tiny details that could thwart the main idea of an artwork.”