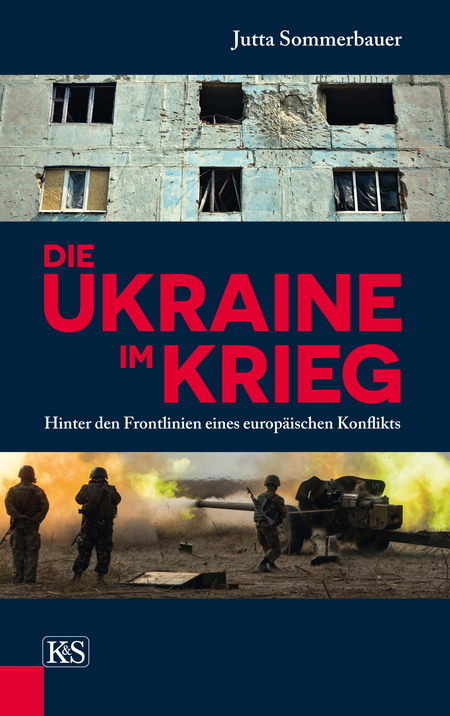

In recent years, Jutta Sommerbauer has been actively covering events in Ukraine for Die Presse, one of the most influential Austrian publications. Her book Ukraine at War (Die Ukraine im Krieg) was published there recently, covering life in the occupied territories, refugees, soldiers’ everyday lives and psychological traumas, as well as personal stories from her trips to eastern Ukraine. It offers a thorough explanation of the situation in Ukraine for the German-speaking audience along with the historical “background” and a depiction of contemporary political realities. These materials are rather exceptional in the Austrian media space. The Day discussed with the author the process of writing the book, the discourse of Ukraine and why many Europeans still see post-Soviet countries as “somewhat Russian.”

You have been covering Ukrainian themes for a long time, starting in 2011. How did you happen to become interested in Ukraine?

“Actually, the reason is simple. We in Die Presse have regional specialization, and our international politics section tasked me with covering the post-Soviet space. It is not only Ukraine and Russia. For example, I covered Bulgaria and Romania for a long time. I spent five years in Bulgaria, worked there as well, went on frequent trips across Europe. Thus, I had some knowledge of the language and experience already, and then just started digging deeper.”

What was the impetus for your decision to write a book about Ukraine?

“I have been traveling a lot in Ukraine over the past two years. In fact, I covered the events of the Euromaidan, the annexation of Crimea, and the war from the very beginning. I empathized with these events at many levels. Subsequently, I felt a need to collect all the material and organize it so that the information was available in a more integrated version. On the one hand, I used my earlier work for the book, on the other hand, it was also the impetus for me to resort to in-depth research which is not always possible in the daily coverage of events. For example, humanitarian topics, the state of civilian population and personal stories are often neglected. It was also a reason to stress some points, find out details, and make the overall picture clearer. This clarification was needed to counteract the ‘Kremlin-friendly’ interpretations of the situation and the dominant opinion which still prevails in Austria. In my opinion, we have failed to understand correctly many things, and some important points were missed. It was important to put some counterpoint to it.”

When talking about the dominant opinion, do you mean the media discourse, or rather the public opinion?

“I mean general trends that are prevalent among the population and in certain political and economic circles. In spite of everything, the media are more critical in their approach to the situation, but if you look, say, at comments sections, or most popular stories – it is eye-opening.”

How would you evaluate this media discourse? What themes get the most coverage?

“The basic problem is that Ukraine is unknown for most people.”

Was or is?

“Was. The situation is changing. But generally, people do not know much about you. What happened in the past 25 years, what changes has your country experienced? Many people still keep in mind the old picture of the Soviet Union and the countries that were formerly part of the USSR are still seen as ‘somewhat Russian.’ It sounds funny, but it is true. Austrians do not realize what the public mood is in Ukraine now, and how much stronger has the national identity become. The theme of Ukraine occasionally made it into the public space during the Orange Revolution and when Viktor Yushchenko was being treated here. People know several soccer clubs as well, I guess, but no more. I am convinced that there is a need for explanation.”

What aspects of the war in Ukraine do you cover in your book?

“I offer a brief historical retrospective of what has happened to Ukraine since the onset of independence in my book. It deals with current events, the Euromaidan, Crimea, the war in eastern Ukraine as well, of course. I tried to explain political developments, but also to explore some individual fields. I mean mostly my stories are about civilians, internally displaced persons, soldiers returning from the war. I also wrote about everyday life in the breakaway territories and the local media situation.”

Who were your interviewees?

“Euromaidan activists, battalion commanders, civilians, psychologists, families who fled from Donetsk and now live in Lviv, soldiers returning from the war. I also spoke with pro-Russian activists to learn about their stance. Also, I interviewed journalists who had to flee from the Donbas and so on...”

What were your personal experiences during these travels across Ukraine?

“I am an ‘outsider.’ This has its advantages and disadvantages. Of course, sometimes it is easy to find interlocutors, because people are interested, they want to explain certain things to a foreigner. On the other hand, there are some very high expectations as to my influence as a European journalist, my ability to convey some specific messages to the whole of Europe, to our politicians. I write texts and get them published, but that does not mean I have a global impact. Also, when foreign journalists come to Ukraine, their nationality is important. It seems to me that Austria’s reputation is not very good. I mean, all these stories of ‘friends of Vladimir Putin,’ oligarchs, business dealings have slightly harmed our reputation. Therefore, we face a slightly different attitude compared, say, to Polish journalists.”

Did you feel it?

“Sometimes it was a topic for discussion. On the other hand, when it comes to Crimea or the separatist-controlled territories, it is an advantage because Austria has not attracted too much attention. I think Americans or Poles find it a little harder to move there freely.”

What were the difficulties you had to endure while collecting material?

“I think I had issues in common with all journalists arriving in a foreign country. It is harder to understand the situation for us than for resident Kyiv-based reporters. We have absolutely no contacts at the start, and have to seek them out slowly. It takes time.”

Have you ever been in a dangerous situation in the east of Ukraine?

“Fortunately, I have not.”

Tell me, what was the Austrian public’s response to your book?

“The book was published just before an anniversary of the Euromaidan and I must say that it did attract much attention. However, I found people’s response somewhat unusual, as some journalists wrote that book was about ‘a forgotten conflict.’ I see it as definitely untrue, because I know that something happens in eastern Ukraine every day. However, for media consumers in German-speaking countries, this conflict is something that has long faded into the background. No one knows what is happening there. Is it war or peace? The media coverage has been shrinking. New texts appear only when it is an anniversary of some event or many people die in some incident. Government crises in Kyiv make it to the news as well. But what about the reforms or the Minsk Agreements’ implementation? This has been lost from sight a little. For the most part, the response to my book was positive.”

Were there no attacks by pro-Russian activists?

“No, there was only one case of an ‘anti-recommendation’ regarding my book. And even then, its authors did not even read this book, but just took an excerpt from another review. It was nothing major.”

What information about Ukraine is Europe lacking, in your opinion?

“We are lacking basic coverage of Ukraine. Other crises have surfaced which are more directly impacting every European. For instance, they include the refugee crisis in Austria, Britain’s exit from the EU, terrorism. I lack information about actions of the Ukrainian government, the state of civilian population, but also some positive stories. What changes are occurring in your society?”

You visited Donetsk and other occupied territories lately. Are the military there open for contact?

“I have received an accreditation, it means that I may go there ‘legally’ and talk with everyone I meet. I could not hold the conversations I wanted, for many of the ‘republican’ leadership were busy at the conflict resolution talks in Minsk. But generally, people are open for contact. Of course, they are not as open as with Russian journalists, but still... They see me as a ‘mouthpiece’ of their ideas. Also, I saw clearly that they were putting a lot of effort in building up their ‘statelet,’ concerning bureaucracy, etc.”

What is your personal sentiment, are you more positive or negative about coming developments?

“I have a rather bleak view of it all. Because fighting is reigniting, the Minsk Agreements’ provisions are not implemented, and it seems to me that there is no willingness to compromise. I think that there will be no escalation, but the war will keep going in this limbo state.”

What Ukrainian themes do you intend to cover in future?

“I have a lot of ideas. It is getting harder for me to get my newspaper’s support for travel to Ukraine. The interest is decreasing. But it is personally very important for me. I will continue to write about your country.”