On October 3, the date of this anniversary, the British Library’s European Studies Blog published an article on this unique artist. The material was illustrated with selected reproductions of the publications preserved in this prestigious library. The article soon drew attention of numerous readers, which could be seen from the numbers of shares. Thus Europe remembered again the old glory of one of the most brilliant representatives of Ukrainian Modernism, devoted promoter and author of topical esthetic ideas of his epoch, inveterate enthusiast of the development of cultural and artistic life in the interwar Lviv.

A lot was written about Pavlo Kovzhun even in his lifetime. He was born on October 3, 1896 in the village of Kostiushky in Ovruch County, Volhynian Governorate. In 1911 (when he, in his own words, felt “a conscious Ukrainian”) Kovzhun began studies at the Kyiv Art College. Among his teachers he named, besides the village educator F. Panasenko, also renowned artists such as Mykola Murashko, Ivan Selezniov, and Anna Kriuher-Prakhova. In the four years of his studies he, then just a boy, became a nationally conscious man as he visited secret gatherings with the participation of Hnat Khotkevych, Mykola Lysenko, Petro Kholodnyi, Ivan Steshenko, Leonid Zhebuniov, and Maksym Synytskyi. Moreover, he edited Holos Yunaka (“The Voice of a Youth”), an underground magazine of the “middle-schooler” union, which he also headed.

At 17 Kovzhun took part in his first joint exhibit of Ukrainian artists in Poltava. At that time he felt most confident in drawing. He was interested in Late Modernism and new developments in European arts, first of all, Futurism.

At this early stage in the development of Kovzhun’s style in drawing one could discern open, formal periphrases of works by Heorhii Narbut, at the time by far the most influential book graphic designer in the entire Russian Empire. Yet the budding artist would not stop at that stage in his quest. He admired the Lithuanian symbolist painter Mikalojus Konstantinas Ciurlionis, got closely acquainted with Pavlo Tychyna, Hnat Mykhailychenko, Anatol Petrytskyi, Robert Lisovskyi, Les Kurbas, and Pylyp Kozytsky. In 1914, together with poet Mykhail Semenko, he founded Ukraine’s first “leftist” art society and was planning a trip to Paris. But in 1915 he was drafted to serve in the Russian army. There he got military training as warrant officer and at the same times led a secret Ukrainian society. Soon after that he was sent to the front, got wounded (twice) in the Carpathians, and eventually returned to Kyiv.

What followed could be seen from his chronological war-time notes: “With the start of the revolution, which caught me at the front, I was supposed to be tried by a court martial for the Ukrainization of my regiment. However, I was able to fully Ukrainize the 26th Artillery Corps where my regiment then belonged; there I published the first military paper at the Romanian front, Kozatska Dumka (“The Cossack Thought”), of which over 30 issues (three times a week) were brought out. I was the military spokesman of the Central Rada’s mission to Romania.” On one of his returns to Kyiv after a bad illness, Kovzhun became active on the artistic front. And again, he is caught between Kyiv and the front. “I have been through typhus, uprising, working simultaneously, when it was possible, in Ukrainian press, and carried out various painting commissions for the army and government. I have been in emigration from the day when the Ukrainian army was interned.”

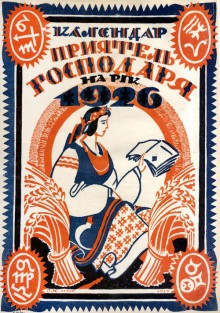

From the camp for interned troops of the Ukrainian People’s Republic’s Army in Pykulychi late in 1921 Kovzhun moves to Lviv to remain there. “Together with other artists and architects I share the joy of the victory of the greater Ukrainian artistic culture over the provincial Galician culture,” will Kovzhun write later as he explored the city’s cultural space. He began with working together with local publishing houses, encouraging their owners to improve the esthetic standards of Ukrainian printed periodicals and books. Having established contact with Galician artists (Mykola Holubets, Mykhailo Osinchuk, Mykola Fediuk, Olena Kulchytska, and Ivan Krushelnytsky among others), he initiated the foundation of the Society of Ukrainian Artists (HDUM). Together with local artists and his colleagues from Central Ukraine Kovzhun was trying to energize the exhibitions in Lviv. He takes up responsibilities of managing various events.

At the society’s first exhibits viewers were impressed with the scale of his quest into the sphere of formal plasticity which inspired the author, whose goal was to merge the national tradition with major trends of European Modernism. Further on, the inveterate Volhynian only increased his activities.

The list of Kovzhun’s Lviv works over a little less than two decades would alone take up too much space. Undoubtedly, it should also be extended with a list of more than 100 items long: publications in books and periodicals, notes on reports made in Berlin in the late 1930s, and a dozen of painted (in cooperation) churches. One of his greatest merits was the organizational establishment of the Association of Independent Ukrainian artists (ANUM), the most active mainstream professional organization of artists of nationwide renown in the first half of the 20th century.

Thanks to no one other than Kovzhun, in the 1930s the modern Ukrainian graphic art triumphed in European cities like Prague, Berlin, and Rome. Due to Kovzhun’s great international clout reproductions of Ukrainian graphic art appeared on the pages of most prestigious professional periodicals: the Polish magazine Grafika, the Czechoslovakian magazine Hollar, and the German monthly Gebrauchsgraphik.

Today his graphic gems make researchers admire his refined authorial style, which merged the most recent developments in art and the echo of the national neo-baroque tradition. On May 15, 1939 death of pneumonia put an end to Kovzhun’s brilliant artistic progress when the artist was 42. In fact, it was total physical exhaustion in all aspects of his artistic, public, and cultural activities. Kovzhun left us a great example of a true Ukrainian and European. Also, he left us his legacy of overcoming fire and passion.