On a Sunday morning, buses with Polish tourists keep pulling up, one by one, at the entrance to Lviv’s Lychakivske Cemetery. Cheerful and smiling, with candles and flowers in hand, they walk, in groups or singly, to the Polish Eaglets memorial to honor the memory of those who fought for Polish statehood in 1918-20. Looking at their venerable attitude to their past, you can’t help but ask yourself: how many Ukrainians who come to Warsaw know that there is an Orthodox cemetery, Volia, there? Have they visited the section where fighters for Ukraine’s freedom and independence lie buried? Did they light a candle of memory at the grave of artist Petro Kholodny, the UNR’s minister of education?

According to The Encyclopedia of Ukrainian Studies (for no mention is made in A Dictionary of Ukrainian Artists), Petro Kholodny Sr., “a prominent impressionist painter with an inclination to lyricism and a neo-Byzantinist,” was born on December 18, 1876, in Pereiaslav, an ancient town of Cossack glory, to the well-known national intellectual family of the Kholodnys (his grandfather and father were the burgomaster and the mayor, respectively). And his ancestors in the maternal line were icon-painters. “The Ukrainian elements dominated overwhelmingly in the town, and a small group of Russian officials was totally alien to us, and their life was not interesting,” the artist recalled later.

In the last two years of being a Kyiv high school student, Petro Kholodny also attended evening classes at Mykola Murashko’s painting school.

After graduating from Kyiv University’s Natural Sciences Department, he began to teach at a technological school’s physics department in 1898 and was appointed principal of a Kyiv commercial school in 1906. Petro combined teaching with art – he painted to his own satisfaction. “Maybe, Kholodny wouldn’t have attached too much importance to this predilection if a friend of his had not sent two of his pictures to a Kyiv exhibit without the artist’s knowledge in 1910,” Professor Roman Yatsiv says. These artworks unexpectedly attracted favorable comments both in the press and among professional artists. Petro Kholodny began to paint intensively – in the next few years he created the canvases Ivasyk and the Witch, Wind, and A Gray Day, studying at the same time the techniques of icon-painting and Ukrainian traditional painting. He reminisced later: “I took deep satisfaction in the pictures Mamai and A Cossack Has a True Soul. My maternal ancestors were painters, and some of their works still remained at home. My awareness grew step by step on the basis of this material. When the war broke out, I clearly knew what I needed. I formulated it half-jokingly for myself as follows: I must find the grindstone [for paints. – Ed.] of my ancestors.”

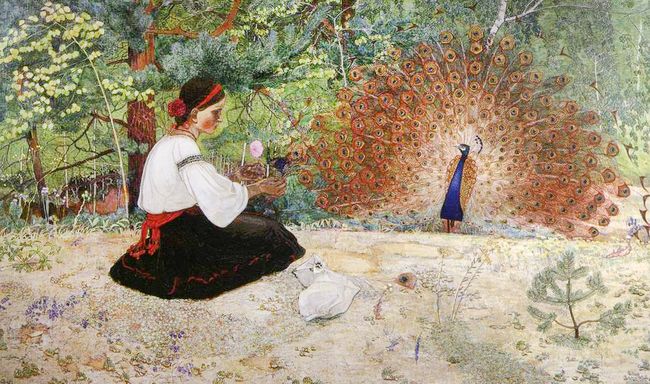

This was confirmed by the 1916 picture A Girl and a Peahen, an impressive canvas full of the poeticized refinery and artistic sensitivity of Ukrainian art nouveau. By this work, the artist immediately positioned himself as one of the leading national symbolists esthetically related to the most outstanding artworks of that period, including pictures by the Austrian Gustav Klimt.

In the years of the revolution and Ukrainian statehood, Kholodny worked at the Public Education Secretariat of the Ukrainian Central Rada and as a deputy minister at the Directory of the Ukrainian National Republic. In November 1920 he, the UNR minister of public education, emigrated to Poland together with the government and the army. The artist documented the whole journey from Kyiv through Zhytomyr, Vinnytsia, Proskuriv, and Kamianets-Podilsky in oil studies and pencil sketches. In Tarnow, at a camp for interned UNR army officers and men, Kholodny “delivered lectures on the current situation and prospects in national art, painted portraits of generals, government ministers, senior and ordinary Cossacks, as well as a series of landscapes.”

In 1921 the artist moves to Galicia – first to Mykolaiv and then to Lviv. Here, on the initiative of the artists who emigrated from eastern Ukraine, he organizes and leads the Society of Promoters of Ukrainian Art, and takes an active part in artistic events and exhibitions in 1922-27. The artist painted the portraits of his contemporaries M. Yunakiv, M. Bezruchko, V. Silsky, M. Omelianovych-Pavlenko, Otaman Yu. Tiutiunnyk, Colonel M. Paliienko, D. Vitovsky, O. Huliai-Hulenko, writers V. Samiilenko and Yu. Romanchuk, the Rev. Yosyp Slipyi; a number of female portraits, as well as historical compositions such as Leaving the Castle, Prince Ihor’s Campaign against the Cumans, and Oh, the Rye in the Field.

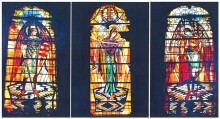

At the same time, the artist also works in the domain of sacral art – icons and stained-glass windows of the Dormition Church in Lviv, an iconostasis and murals at the Holy Ghost Chapel of the Lviv Theological Seminary, a number of icons at the parish churches in the villages of Radelychi, Kholoiv, Borovychi, and Zubets. These works combine the Ukrainian art tradition and Byzantine iconography with the expressive coloristic techniques of folk art.

The ordeals of life and hard work undermined the artist’s health. He agonized over having to live apart from his kinsfolk. According to Professor Yurii Teliachy, a researcher of Kholodny’s life story, “in the 1920s he declined the official invitation to return to Soviet Ukraine and said he would only do so together with the UNR government and army.” The artist died on June 7, 1930, in Warsaw. In the words of Stepan Siropolko, Petro Kholodny was buried “at the Wolskie cemetery in a zinc coffin, taking into account the likelihood of transferring the dead body to his native land in the future.” The obituary published on July 1, 1930, in the New York newspaper Svoboda said the artist had “died wishing to be buried in Lviv which he liked as much as his faraway Kyiv.”

In 1931 the National Museum of Lviv staged a posthumous exhibit of about 350 Kholodny’s works. A considerable part of these works were destroyed or retouched as “ideologically harmful items of nationalist art” during the Soviet occupation of Lviv.

In conclusion of the article on the Ukrainian statesman and a talented “well-known and, at the same time, unknown artist” and his impact on the Ukrainian cultural process, I would like to quote Professor Halyna Stelmashchuk, the author of the monograph Ukrainian Artists in the World (Lviv, 2013): “As far back as 1916 he (Petro Kholodny) began to apply the old icon-painting technique in religious and lay compositions which he deliberately vested with some stylistic features of the Byzantine tradition, transforming the latter in the spirit of the contemporary nouveau art. Therefore, in addition to Mykhailo Boichuk and Oleksa Novakivsky, Petro Kholodny was one of the founders of the Ukrainian national style in figurative art known as ‘neo-Byzantinism.’”