We often complain that Ukraine lacks spiritual role models in Ukraine. But do we often realize that true and non-fallacious spiritual role models have always existed and will always exist under an indispensable condition: society must see and support these people, meet them halfway, and follow their example? This means making spiritual efforts, sometimes difficult and painful, and improving yourself. It is hard work, for nobody will ever bring you on a silver platter the heritage a moral authority has created in torments, sufferings, and inner struggle. It is an illusion, to say the least. The way to Taras Shevchenko and Lesia Ukrainka, Ivan Franko and Oleksandr Dovzhenko, Vasyl Stus and Andrei Sheptytsky, Lubomyr Husar and Josyf Slipyj is not so simple.

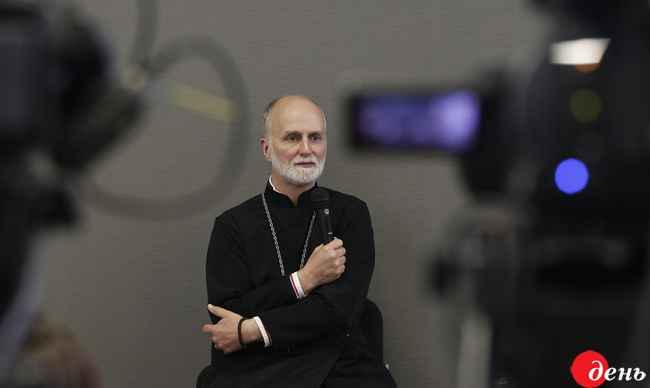

It is the spiritual exploit and exalted service to the Lord and his own people of Cardinal Josyf Slipyj (born Yosyf Kobernytsky-Dychkovsky, February 17, 1892 – July 7, 1984), Major Archbishop of Lviv, Primate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church, that a meeting with H.E. Borys Gudziak, Bishop of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Eparchy of Paris, at the Ukrainian Catholic University’s Kyiv Center was dedicated to. This event was really necessary, informative, and meaningful, for it was about one of the 20th-century Ukraine’s greatest moral authorities (millions of our people are only beginning to be aware of the magnitude of Cardinal Slipyj’s personality), while Bishop Gudziak had a privilege to know the zealot personally in the last years of his life, when the cardinal was about 90. Knowing that too little time was left to carry out his plans, he tried not to waste even a minute.

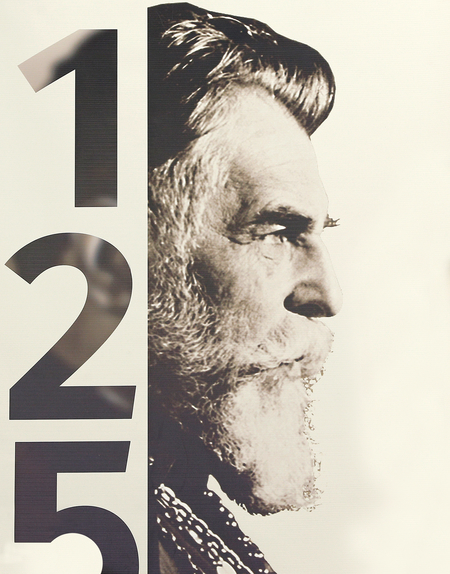

Here is a brief reference for those readers who do not know much about Josyf Slipyj. Yosyf Kobernytsky-Dychkovsky (legend has it that the nickname Slipyj (“blind”) was applied to his distant ancestor who had his eyes gouged on Tsar Peter’s orders for supporting Hetman Ivan Mazepa) was born in the village of Zazdrist, Terebovlia county, Galicia, to a large profoundly religious peasant family. From his early childhood, the talented boy nurtured a dream to become a professor of the humanities and a priest. When Josyf was 11, he met Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky who cared about the would-be Primate of the Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church (UGCC) and was his teacher, guide, and mentor until his own death in November 1944, when Josyf Slipyj succeeded him. The young Josyf received a thorough education in Innsbruck and Rome (before that, in 1911, he graduated with honors from the Ternopil Ukrainian High School). In 1917, Metropolitan Sheptytsky ordained Josyf Slipyj as a priest. Josyf became a professor at the Lviv Greek Catholic Theological Seminary in 1922 and Rector of the Lviv Theological Academy in 1929. In December 1939, during the Soviet occupation, Metropolitan Sheptytsky secretly ordained Josyf Slipyj as a bishop with a right to succeed, saying: “We need a person who will not break down under any circumstances.”

Following Andrei Sheptytsky’s death on November 1, 1944, Slipyj became the Metropolitan of Halych. Together with other UGCC hierarchs, he was arrested on April 11, 1945, on the secret orders of Stalin and Beriya. Slipyj flatly rejected the offer to convert to Muscovite Orthodoxy, for which he was promised not only liberation, but also a very high office at the Moscow Patriarchate. He said: “I will never betray my persecuted Ukrainian church.” He spent a total of 18 years (1945-63) in the prison camps of Siberia and Mordovia. During this period, he was gravely ill, was twice on the threshold of death, and had his feet badly frostbitten. But it is in those years that he wrote a fundamental multivolume History of Ecumenical Church in Ukraine which was secretly sent abroad for publication.

Slipyj was freed by Nikita Khrushchev in February 1963 at the request of Pope John XXIII and US President John F. Kennedy. He spent the last 20 years of his life in Rome, from where he paid pastoral visits to all the continents of Earth. In January 1965, Pope Paul VI honored him with the title and dignity of cardinal. In spite of a venerable age, Slipyj was making extremely active and self-denying efforts to establish UGCC parishes and centers all over the world. He founded St. Clement Catholic University in 1963 and helped build St. Sophia’s Cathedral in Rome in 1969. In 1978, at the audience in honor of Pope John Paul II’s ascension to the throne, the pontiff rose and approached Slipyj to welcome him, which was in fact a breach of protocol.

Borys Gudziak spoke about this prominent figure at a meeting called “What Will History Say about You One Day?” Let us try to set forth his most important conclusions as concisely as possible.

1 Josyf Slipyj was a human being, not an icon. But this person witnessed and participated in many high-profile battles of the 20th century – battles against totalitarianism which aimed to turn humans into biomass or to eliminate them at all. Slipyj held out in this struggle, and this power of spirit is a great call to and lesson for us.

2 He arrived in Rome at the age of 71 (Khrushchev did not expect Slipyj to live long after what he had gone through), came “without anything” if we speak in vulgar-material terms – he had absolutely no property or money. But he “regained a new life,” as he once said himself, although he had lost his 18 best years behind bars. What is more, he did not like speaking about his personal suffering and patience, preferring to think and speak about the suffering and patience of all the Ukrainian people.

3 He was extremely exacting to himself (above all) and to his entourage. He looked like the one who speaks right from the Bible’s pages, like a true-to-life non-canonical biblical patriarch. He often regretted being too gentle with somebody, but he never regretted being too strict to somebody.

4 Yet if you won his confidence and worked properly, he never betrayed you and could intercede for you with very influential people, even though he might criticize you very scathingly. For which I am personally very grateful to him: his life had a dramatic effect on mine. But for him, I would not be standing now before you.

5 He always called: “Wish great things!” This call of his, as well as another, very important, opinion – “the only capital of Ukrainians is their own pride and attitude,” – must be heeded right now. We can say Josyf Slipyj was the face of Ukrainians in Europe and the rest of the world, and Ukrainian identity was forming around him. He knew like no one else how to mobilize young people, for he knew how to set a very difficult, even exhausting, but vital and concrete goal to you.

5 He was deeply worried about what history will say about us. He was an absolutely devout person who communicated with God very closely. And communication with God means, above all, the ability to listen… Then the great sacrament of being reveals the sacraments of other people. He was not deprived of his own “ego” (everyone has it) but, starting from his childhood, when he trained himself to daily prayers and confessions to the Lord and, hence, to self-discipline, he managed to curb this “ego” in himself through sincerity, honesty, and frankness.

7 As Metropolitan Andrei Sheptytsky was the spiritual father of Josyf Slipyj, so the latter was the spiritual mentor of very many UGCC clergymen and figures. Among them (perhaps above all) is His Beatitude Lubomyr Husar whom we lost recently and whom he duly appreciated and ordained as a bishop as far back as 1977 after many years of close spiritual communication (even though without formal consent from Pope Paul VI). This life-giving continuity of moral role models is of paramount importance to Ukraine.

8 Today, the literal reproduction of Sheptytsky and Slipyj is practically impossible in Ukraine, as is impossible, for example, the emergence of Winston Churchill and other giants of this scale. But we not only can but also must do our sacred moral duty – to learn from them under the entirely different historical circumstances, following not the outer “letter” but the inner “spirit” of their lifetime exploit.

***

Cardinal Josyf Slipyj is still calling upon us to wish great things. He could not stand idlers and ne’er-do-wells. He always encouraged his aides to study and defend dissertations. But, in spite of his outward sternness (he was almost two meters tall), he always beamed a natural spiritual joy. He never allowed kissing his hands. “Don’t kiss the hand of a convict. I need no kisses. You’d better do your work,” he used to say. And his episcopal emblem read a famous Latin phrase, “Per aspera ad astra” (“Through hardships to the stars”).