When Seneca and Horace, Virgil and Sophocles, Ovid and Aeschylus address us from the pages of Ukrainian translations of their Greek and Latin works, they do it with the voice of the interpreter, author, and scholar Andrii Sodomora. In turn, we try to enable his voice to reach our readers from the pages of Den newspaper as often as possible. During the Publishers’ Forum in Lviv, Sodomora visited the launch of Den’s latest book project. So, it was about the book The Crown, or Heritage of the Rus’ Kingdom as well as journalism and history that Sodomora talked to Den during this latest interview.

Reading is making a step forward, is not it? What role does the book have in the formation of one’s personality?

“‘A day is a stage on life’s journey,’ said the chief Roman stoic. And life is, in fact, the road which we go along. We go somewhere, come back or just wander. Today, despite the fact that we are going to Europe, we are also on the most important path which is the path back to ourselves, to our history, to our sources. To go to someone, you need to be someone. ‘Where you go matters less than who you are when you go,’ – I am again quoting Seneca who shaped people’s personalities and opposed depersonalization with his opinions. A private person can afford to just go nowhere for a while, like, say, Paul Verlaine’s Autumn Song’s persona does: ‘And I go / Where the winds know, / Broken and brief, / To and fro, / As the winds blow / A dead leaf.’ A people is another matter altogether: it should be ever itself, go against the evil winds, do not allow these winds to carry us back and forth or even blow us away from the world’s scene. We should get to know ourselves by not just reading, but thinking through our thousand-year history (the ongoing war is really fought not for territory, but for a place in history). And thinking is harder than just reading: while swimming through information flows, we prefer ‘bare facts,’ we savor unusual cases and news. ‘Men are naturally curious; they are delighted even by the baldest relation of facts, and so we see them carried away even by little stories and anecdotes,’ we read in one of Pliny the Younger’s letters. That is why it is so easy to zombiefy and so hard to encourage thoughtful reading, and thinking in general, although it is in the latter that ‘all our dignity consists,’ to quote Blaise Pascal. Also, regarding ‘bare facts,’ let us listen to Lucian’s voice in his How to Write History: ‘Facts are not to be collected at haphazard, but with careful, laborious, repeated investigation...’”

So, let us speak of journalism and history: what, in your opinion, are their specific features in the current reality?

“That is why the work of a historian, a journalist is becoming so important nowadays: it is necessary to have not only the courage required to present facts, but also the ability to think, comprehend, and attract the public to thinking, not consumption; to creating their own vision, and not to spectacles. In a word, all of us, not just some elect individuals, are called upon to find out who we are, where we come from, and once we see it, ‘to look beyond the horizon’ as well, to discern where we are going. Then, we will not be ‘resourceless,’ as Sophocles puts it: ‘yea, he hath resource for all; without resource he meets nothing that must come’ (‘he’ meaning one who looks forward with his own eyes, his own opinion). Then we will cease abandoning our patrimony into the hands of others (I mean language problems, hostility to high style in particular), then we will get rid of the inferiority complex, then we will not hesitate, even on the world stage, to speak in our own deeply-rooted Ukrainian language, we will not hurry to declare our world citizenship and we will not boast of knowing yet another lingua franca. We need to ‘demine’ not only the real, but also the spiritual space – to avoid repeating our historical mistakes and at the same time to neutralize the hostile lie. These are the first accents set by Larysa Ivshyna in her sincere, emotional and profound ‘Word to Readers,’ which comprises so much that is fresh and unexpected, in particular, concerning the constitutional monarchy in the 21st century; all this comes from a panoramic vision of world history and global thinking. ‘Word to Readers’ introduces us to a book which is another, and very important step on the way back to our tomorrow; a book with the visually beautiful and ear-pleasing title: The Crown, or Heritage of the Rus’ Kingdom.”

In your opinion, how, in general, should one read such books as the one in question, I mean The Crown?

“To read, we must first of all think, that is, we need to see what is behind the word, in the depths of the word. Half of all the mistakes and troubles, as Rene Descartes taught following the Stoics, come from the erroneous understanding of words: we must clarify what is democracy, elite, independence, nobility, heritage, courage, propaganda, in the end – what is the crown. In order to avoid those mistakes and misfortunes, we need, I repeat, to read and think, to return to the real, liberal education that forms a person, and not some ‘know-it-all.’ Here is what, for instance, Boethius had to say about the nobility: ‘If ye behold your being’s source, and God’s supreme design, None is degenerate, none base, unless by taint of sin’ (and the gravest sin is the thirst for enrichment at the expense of others); such noble persons who work for the good of their kin and people, and not for their own, make up an elite that was destroyed time and again precisely because they worked for the good of their people (it was our enemies that called them ‘enemies of the people’); it is to it, the national elite, that most attention is paid, and quite rightly, in the preface and the book. Democracy is not the rule of a population that expects only a material improvement in life, but the rule of a people that goes up, although it had been locked into a cellar. Independence is a high responsibility; it is high because it makes us responsible to God, who, having called the man into being and given him free choice, wants him to choose light, and not darkness: ‘only responsible and cultured peoples can be free’ is the concise formula included in ‘Word to Readers.’ Courage is the sum total of all virtues, not just bravery. The heritage should go from good hands into good hands, so that it increase, and does not decline: the veneration of ancestors and descendants is an important teaching of the ancients. The duty (a keyword of Ivan Franko’s writing) does not bind, but rather obliges and makes a person into a social being. Contemplation is not thoughtlessness (‘...the people were seated in front of the TV and robbed’ is a bitter truth), not anything leading to boredom, but the highest pleasure from live – because we talk with living nature and not with a screen – and imaginative thinking: ‘Thinking is more interesting than knowledge, and contemplation is most valuable,’ Johann Wolfgang von Goethe seems to have said. Inertness is the Latin for the lack of creativity: the elite of the times of Volodymyr the Great and Yaroslav the Wise, who are mentioned in the preface, were not inert: the construction of St. Sophia of Kyiv, which was the strategic task of the then elite, is a high, exemplar case of creative spirituality. Intelligence (also coming from Latin) is, among other things, the ability to make the right choice, to take the right step, this is understanding, and this kind of intelligence should now be developed and protected. It is nice that The Crown has this topic raised so frequently. I remember, from a memoir in the book, Otto von Habsburg (Vasyl Vyshyvany), the nephew of the last emperor of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, who was an extremely intelligent man with an excellent education, he knew six languages and understood the world well. The main thing was that he was modest; without this trait, even a polyglot would not be an intellectual in any way. Therefore: ‘We clarify the meanings of words...’ Having clarified them, we combine them with deeds, confirm them with deeds, as the Stoic philosophers advised, who were especially respected in Ukraine (including by our Cossacks); they called for perseverance and endurance, persistence and zeal, honesty and sociability, dignity and contempt for luxury, patience and courage not to bow down even before Fortune...”

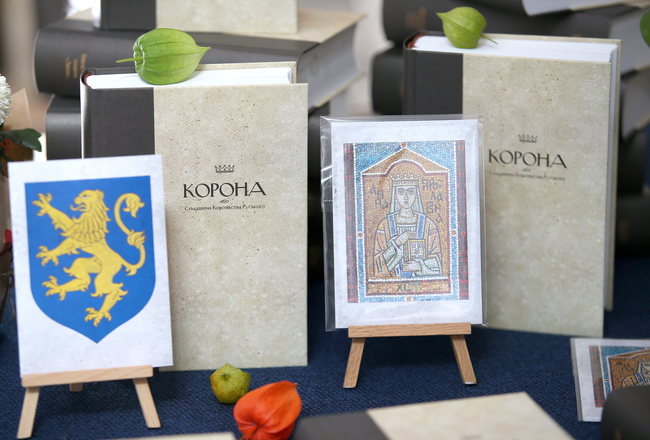

Photo by Artem SLIPACHUK, The Day

And what about the crown? What associations do you have when this word is uttered, what do you see behind it?

“The crown (a Latin word) was initially a wreath of flowers or leaves; it is a plexus where the end is also the beginning, it represents the harmony of colors, the concord, and also, in our time, serves as a symbol of robustness, unity, and most importantly – continuity and connection, while the task of the book we are talking about, as it is stated in the preface, is to ‘connect’ the times, because without this connection everything withers and disintegrates. A very interesting idea from ‘Word to Readers’ positions Ukraine as a transformer country (Kyivan Rus’, the Rus’ Kingdom, the Duchy of Lithuania, etc.). The attentive reader will immediately remember Ovid’s Metamorphoses and the guiding opinion of the author of the poem: ‘Everything changes, not dies…’ However, when talking about the people, we need great, shared efforts, for otherwise, Taras Shevchenko’s words ‘Ukraine, you will perish, vanish…’ will come true. Educational work is needed, but not at the level of memorizing rules, dates, stories (they do not really enlighten anyone): the defining feature of it should be building up not just memory, but emotional memory, one existing at the level of feelings: it is preserved in the folk song, which, if we are to believe the Bard of Ukraine, ‘will never die or vanish,’ in our ancient customs, and most importantly in our juicy, and not only ‘correct’ (‘beautiful’) language. And it, this language, which really was the soul of the people (there is less and less of that soulfulness), gets so little attention from us, and worse still, we ourselves cripple it! ‘We have always had enough impulse, but not enough continuity’ – for the umpteenth time I remember that entry in the diary of Mykhailo Bilyk, a translator of Virgil’s Aeneid. By the way, the language of our Aeneid or, say, Odyssey in the interpretation of Petro Nishchynsky (Baida) is an example of just such a phraseologically rich, singing, colorful language of our ancestors; to feel this language, to cherish its most important, national, predetermined by our history features (and we lose them as we fight the lexical Russian contamination only) is to cherish what is most valuable: the connection between generations, something that should not perish. And another thing: the Romans, and they knew a thing or two about the laws and state-building, first of all cared about its historical foundations, its sources (remember the same poem by Virgil or Livy’s historical work Books from the Foundation of the City), and also about returning to the land, to the ‘customs of ancestors,’ without which the moral improvement of society will remain at the level of declarations. The fate of Ukraine, however, was frequently associated with Troy, because our history was like that, as described by Bohdan Lepky: ‘Oh my land, the holy ruin / The modern Troy in its ashes!’ But we must rise from the ashes, rise from the dead, as Phoenix did: ‘You will rise from the dead, my Ukraine...’ – never did we lose faith, at least in the song.”

The Crown, of course, often uses the term “constitutional monarchy.” What do you say about this?

“When I read about the constitutional monarchy, for some reason I remember the famous Mykyta the Fox by Ivan Franko, of course, not in the Soviet interpretation which had it as a mere children’s fairy tale, but as an uncorrected, authentic poem primarily targeting the conscious strata of our peasantry (with congenial illustrations by Edward Kozak), which in allegorical images explains Niccolo Machiavelli’s advise: ‘If you cannot be a lion, be a fox’ (politics often requires not only wisdom, but cunning as well: the Fox, like Odysseus and his fellow Aeneas, is a winner, an ingenious figure, ‘in every kind of mischief mellow,’ just like our Cossack wizards: they prevailed over evil not only through brute force, but also through savvy, agile actions). So look: the maned Lion, who wears a crown on his head, suffered the least in the end (all woes befell his unlucky animal entourage, who have all the human shortcomings, primarily insatiability and stupidity, and suffered a lot at the Fox’s hands). It does not seem that Franko ‘rails at the predatory nature of the autocracy, ruthlessly ridicules the nobility’ (from the annotation to the 1981 edition): a crown is still a crown, especially when it sits on the head of a statesman who is smart and wise, worthy of this expensive decoration.”

What is your overall impression of the book? What opinions come forward on the basis of the articles it comprises?

“The Crown needs to be re-read and thought through; it involves respected contributors and respectable subjects that require knowledge and competence in these fields, so I cannot now fully comprehend or properly evaluate everything in the book. I will just allow myself to repeat: it is such a wreath – a plexus of interesting, unconventional thoughts that help us to look back on our past, and consequently, to see the future – that is extremely necessary for the contemporary reader, so that those who are still shy of their own culture will finally have the scales falling from their eyes, for otherwise, no computerization will enable us to see the light of God. By the way, about the light. It is nice that in The Crown’s contributions, we come almost at every step across something that immediately immerses one into antiquity, which (although not yet Christian), cherished, in fact, God’s light as the gold of the soul. For example, ‘The Philosopher on the Throne’ (the title of the contribution about a Ukrainian prince) immediately makes one think of the idea of the educated ruler, of the emperor and philosopher Marcus Aurelius. We open at random his Meditations (To Himself) – and come across what is most painful for us now: ‘Nature has fixed bounds both to eating and drinking, and yet thou goest beyond these bounds, beyond what is sufficient,’ he addresses his imaginary interlocutor (of course, not one of the ‘elect’). Crossing such bounds is a sin, in the most diverse spheres, and it is almost the most revealing feature in the portrait of the consumer era, which lets the spiritual matters decay, but promotes material things in a shrill voice (‘to advertise’ means to shout out). When reading the preface, I stopped on the word ‘calligraphy’ (used in discussing Pylyp Orlyk’s letters). I remembered my childhood and a line from a favorite song of our country: ‘A stream is meandering near a grove.’ I recalled the handwriting of Nature – and the canals built at the time of ‘land improvement’ campaigns that crossed out this handwriting, so we must restore it, and with it our own character, to extinguish the insolence and cheekiness cherished in the totalitarian era. At the mention of the ship for which no wind is favorable if one does not know to which port one is sailing, I recalled the words of Franko: ‘He who has no destination / Will never achieve anything: / Oh the boat! If you are sailing, you should know where to,’ and their prototypes: ‘the ship of state,’ which became a toy of winds, in Alcaeus’s and Horace’s works. It is pleasant, but at the same time, it is important that in the vastness of European history, from the temporal distance, we see the ‘light points’ – the cells of our culture and iconic figures with their very names speaking volumes: Yaroslav the Wise, Volodymyr Monomakh and his Instruction to the Children, Yaroslav Osmomysl, King Danylo, Prince Kostiantyn Ostrozky, Hetman Petro Sahaidachny who defended European culture from an eastern invasion even as he nurtured it, military genius with European education Bohdan Khmelnytsky, and Hetman Ivan Mazepa who got Europe fascinated with himself. In the end, in remembering our ancestors, we return our own to ourselves. Back in the time of the ancients, the greatest disgrace was either to squander the parental inheritance, or, worse still, to hand it over to strangers.”

What did you commit to memory immediately? Perhaps reading the book brought back some memories?

“I live in Lviv in Linkolna Street (formerly Dimitrova Street); neighboring parallel streets are Hetmana Mazepy (formerly Imeni Mista Pech Street) and Viacheslava Lypynskoho (formerly Ulianovska Street). The difference is obvious. However, are all the residents of these streets trying to know as much as possible about Mazepa, about Lypynsky? These very apt words from the preface caught my attention as well: ‘Today we can overcome cultural destruction only by setting ourselves a super-objective. Without this, postcolonial thinking will persist by inertia, and new street names will not help this.’ Once, I remember, a passerby addressed me: ‘Where is Ruska Street?’ Before I had a chance to respond, he continued: ‘But it has probably already been renamed’ – and went away. On the day of the Ukrainian independence referendum of 1991, I was fortunate to visit the observation platform of the Washington Monument (next to the Lincoln Memorial) in the city of Washington. Our guide, having learned that there was a Ukrainian in the group, shook my hand and congratulated me on independence; I remember the shake of his hand, and even the name has been preserved by my memory: John Lackwood. We are present in a European, global context.”

What would you wish the readers of Den/The Day, the readers of The Crown, and our contemporaries in general?

“One of the meanings of the Latin noun ‘corona’ is the circle of listeners, spectators, interlocutors, in general people who are gathered in a circle. I would like to wish that the circle of readers of Den/The Day and this new book The Crown alike expands, that all of us really aspire and become able to comprehend our thousand-year history; so that every day, every ‘stage of our life’ is directed both to ourselves and to people, I mean good and benevolent ones. And besides, since the war is going on, I want to recall the words of Horace addressed to Rome, which, as if it was a mighty oak, ‘Draws strength and life / From the blade that cuts it.’”