Oleksandr Arkhypenko once said: “My art is an expression of longing for something which I myself cannot define. Most certainly, my greatest longing is my lost Fatherland.” I do not know if Andrii Mentukh would agree; I do not know his attitude towards this great sculptor. I just do not recall us talking about Ukrainian genius.

Yet I am deeply convinced that Mentukh’s personality was shaped not by the comfort of a predictable carefree youth or a life that resembled a bed of roses. He has known plenty of trials, suffering, choices, hesitations, and temptations. He is another vivid example of a genuine artistic talent, which most typically rises and flourishes in troubled times, while in hothouse conditions it mostly degenerates and dies.

Andrii Mentukh was born in 1929 in Kariv, a village halfway between Lviv and Sokal. When he was only 15, he was warned by a fellow villager that the Soviet secret police suspected him to have contacts with insurgents and were looking for him. The teenager had to make a most complicated, decisive choice. Either to go home, get caught by the NKVD officers, and accompany his parents and younger brother to a camp somewhere near Vorkuta in the far north, or to forget the path to his house, cross the infamous Curzon Line, and take a step into the dangerous and unknown future, undressed and empty-handed. The teen chose for the latter. He was lucky: he did not get lost and finally he was able to find allies. There, among insurgents from Danyliv, he grew up and matured as an agent responsible for information and communications. He was to experience dangers and unrest, the darkness of tiny hide-outs, the despair after the defeat of Ukrainian armed resistance, and survive a serious injury. And when his underground period came to an end, he was able to avoid what seemed unavoidable: to get out from the war-scorched Zakerzonnia, torn and bleeding from fratricidal clashes, and get to the north of Poland unharmed.

Mentukh found himself in Gdansk. It was a story of a miraculous survival in a hostile environment, among suspicion, under unbearable conditions where human life, freedom, and dignity were not worth a red cent.

He has survived, but he missed his Fatherland. Mentukh paid a very high prize to redeem himself, and the dearest and scariest that lurked in him was called memory. I would also call it longing. And this longing was even worse because he could not overcome it otherwise than by constant, external and internal struggle, a one-man contest for his own self, his dignity, honor, and devotion to his Ukrainian name.

Against the backdrop of the volcanic landscape between reality and memory, Mentukh could not but grow into maturity as an artist, a painter with a principled conscience on the edge of the past and future. Only in the sphere of art did fate promise him an ability to speak from beyond the threshold of his forced silence, to manifest the sense of human life adventure with its good and bad, victories and failures, despicability and beauty, and the unattainable universal fatherland, which resembled both a dream and a mirage at the same time.

Mentukh was to become a painter. He deserved this by victoriously growing through calamities, just like Arkhypenko, rising, gaining the right to express himself in the lofty realms of truth, beauty, and humanity.

As soon as he adapted to the new environment, concealing (sometimes on the verge of failure) the truth of the path that had led him to the tereny odzyskane (Polish for “regained territories”), Mentukh became a student of the secondary art school in Gdynia. Upon graduation he went for master’s degree in Gdansk, which he received from the local Academy in 1959. Later he was able to become an adjunct (and later, a senior lecturer) at the Academy’s department of drawing and painting. (By the way, he did not even try to earn professorship, being very realistic about his political past). Instead, he plunged into creativity.

He actively participated in numerous exhibits in Gdansk, Warsaw, Krakow, and other Polish cities.

Mentukh always needed to stand up for his right for creative and personal freedom, even as the Polish security service kept an eye on him, following his activities closely up to 1984. However, Mentukh’s prudent behavior and artistic talent helped him a lot to protect himself, establish and defend his creative standpoint.

He organized a series of personal exhibits in Bucharest, Sofia, Moscow, St. Petersburg, Berlin, and Pont Levin, making a worthy contribution to Polish painting. His paintings find their way to the museums of Warsaw (the National Museum), Szczecin, Gdansk, Opole, to the depositories of the Polish Ministry of Culture etc. The name of Mentukh, an outstanding author of original paintings, appears next to the names of most outstanding Polish artists. His individual artistic hand, unique form-shaping style are maturing, becoming more and more convincing and at the same time retain their iconic simplicity, delicacy, and deep mysteriousness. Mentukh becomes a notable figure in Polish culture, and brilliant prospects are ready to open to him but for his Ukrainian spirit, which the artist never gave up, and would never do so, no matter how life treated him.

He boldly defies political surveillance and takes an active part in the life of the Ukrainian diaspora in Poland. Mentukh works on scenography for the Festivals of Ukrainian Culture in Sopot, becomes active in Ukrainian communities, paints the portraits of Taras Shevchenko, Lesia Ukrainka, Ivan Franko, Ukrainian Hetmans, and designs the covers and front pages of five yearly Ukrainian Calendars. All mentioned above is but a small part from Mentukh’s contribution to the activities of our diaspora in Poland. And it is just such a part which cannot fully soothe his nostalgia for his lost Fatherland with its eternal problems and its unique, centuries-old archetype.

After the collapse of the USSR, Mentukh becomes most actively involved in Ukrainian artistic life. In 1989 (together with the unforgettable Emmanuil Mysko) he chairs the jury and participates in the International Biennial Impreza in Ivano-Frankivsk; he chaired the jury of this cultural project in the years to follow, 1991-93; he becomes honorary member of the National Union of Artists of Ukraine; he wins Vasyl Stus Award and co-organizers the exhibition of contemporary Ukrainian art in Kyiv and in Polish cities; he takes part in the exhibition at the Pivdenny Khrest (Southern Cross) at the Odesa Literary Museum, as part of the Festival of the Association of Ukrainian Writers; he holds personal exhibits at the Lviv National Gallery of Arts, the Andrii Sheptytsky National Museum of Lviv, twice at the National Art Museum in Kyiv, at the Khmelnytsky Art Museum, the Taras Shevchenko National Museum in Kyiv, and the Shevchenko Museum in Kaniv.

Mentukh’s presence in independent Ukraine’s cultural life is not only consistent and long-lasting, but first and foremost, it is highly valuable. In any art project Mentukh’s art is manifested as a meaningful phenomenon of sterling quality carrying his signature token image: absolutely simple, yet precise, impressive, and essential. The artist speaks to the viewer as a competent, erudite, thoughtful person, knowing the Sublime and the True, the suffering and the unmistakability of Being, the worthiness and the perseverance in dignity.

His paintings are signs on the thoroughfares of human trips to the unreachable horizon. They persistently and consistently remind of our immortal spiritual principle, of the blissfulness of sublime harmony, of the weight of truth which is within reach, of the noble nostalgia for the unattainable truth, of the Beauty which is easy to touch – but not so easy for idle or hard-hearted people.

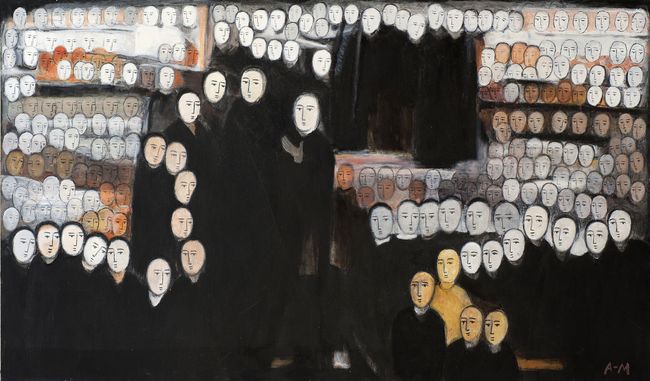

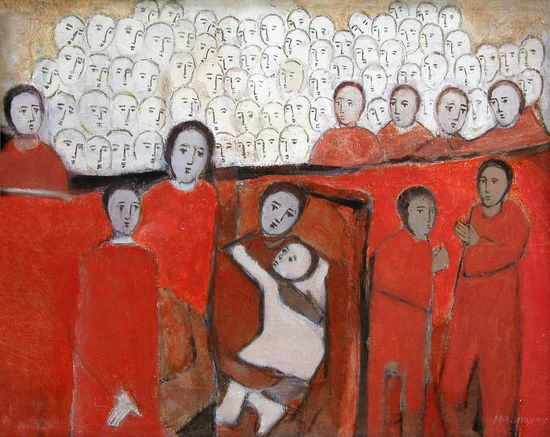

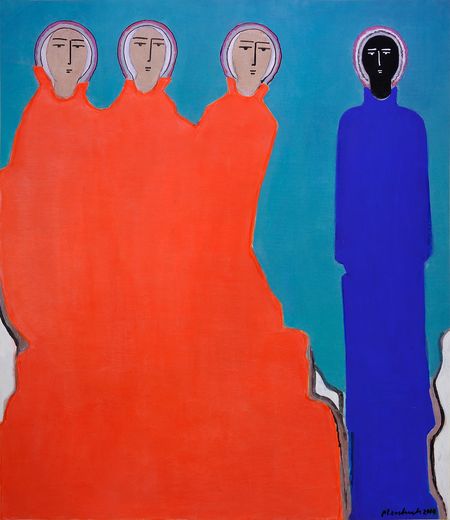

There is some mysterious magic of Mentukh’s open signs, the symbols of human faces, figures, communities. Rounded like pebbles, images of faces between train tracks, elongated signs of silhouettes, solid signs of human gatherings, encoded into eternally imperceptible evacuation: all of these signs seem equal cliches at first glance. However, in a magical way each of these pseudo-cliches arises before the viewer with its unique biography, fate, and cosmos.

And this is no carefree cosmos. It is a cosmos which holds the excessive, impermissible hatred, misplaced and vain human worries, frozen vanity, animosity, greed, and thirst. It is a different Composition Cosmos, placid and alarming at the same time, consistently devoid of the usual human imperfection and willfulness.

Mentukh speaks of important, true things without reproaching. He shows Beauty without embellishments, exaltation, or clownishness. He gives sensible and simple evidence of the sublime. He is resilient to a maximum, using economical, minimalistic means of expression. He reminds about the important things silently, via his symbolic paintings.

As a viewer, today and tomorrow you will trust in Mentukh and confide in him, a personality resulting from sterling quality, conscious interpretation, and the sense of that sublime longing which can only be found in exceptional, responsible, and noble Personalities.

Liubomyr Medvid is a holder of the Shevchenko National Prize, academician, People’s Artist of Ukraine