Borys Malynovsky devoted 70 years of his life to science. At the age of 90, he is a famous scientist — one of the creators of the first computers. Today the scientist is an advisor to the Board of the Glushkov Institute of Cybernetics (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine), an Honored Science and Technology Worker, and the House of Scientists’ head of the board (National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine). Having joined Ukrainian science in the early 1950s, Malynovsky witnessed and participated in the most productive period in its history. It was then that the first computers started to appear; scientists designed them step-by-step, finding simpler solutions to complex problems using new equipment.

Malynovsky is the chief designer of “Dnepr,” the USSR’s first general-purpose control computer. “Dnepr” facilitated the work of half a thousand enterprises, plants, and scientific institutions. After the collapse of the USSR, the situation in science changed dramatically. However, nothing can stop a real scientist’s thirst for constant innovation, updating and generating new ideas.

Mr. Malynovsky, what led you to become a scientist?

“I remember the past

With my every nerve

As if I were living

In two dimensions:

In my epoch and in 1941…

These several lines by the wonderful front-line poetess Yulia Dunina express the main milestone in my life. I am 90 now, but the war remains in my mind all the time. It determined my character, occupation, way of working, and persistence in life. After high school, I had a strong desire to enter an institute, but it never happened. After two years of military service, the war began. Out of 1,418 days, I spent 1,000 days at different fronts. There is a constant tension, and you are pushed to the limit. I was twice wounded and once contused. The war is not just physical pain, it is above all spiritual: my elder 24-year old brother Lev died, he was a tanker. In a word, my life was totally changed; and not only mine, the whole young generation that took part in the war at the age of 18-25 experienced the same thing.

“When I returned home, I had the impression that my mind was erased and restoring knowledge was impossible. I could not even dream about science, I planned to become a military-school instructor, as I went from sergeant to battery commander during the war. I am not sure what my life would have been like if my father, remembering my late brother, had not insisted on my entering the institute where my brother had studied before the war. I soon became a student of the Electro-Mechanical Department at the Ivanovo Energy Institute. Young people sacrificed the most during the war. Out of every hundred from my generation of 20-something-year-olds, only five to ten people returned home.”

What attracted you to Ukraine, why did you decide to move to Kyiv?

“First of all there were talented, leading scientists who worked in Ukraine. Serhii Lebedev was one of them; he was a man of genius, I studied his books while in the institute. Control automation interested me the most. Lebedev worked on this topic before the war. However, at that time I was already married and had a son. I dared to leave my family and went to Ukraine to become a graduate student in the Institute of Electrical Engineering at the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic.”

How serious was the confidentiality issue regarding scientific inventions at that time? Did you feel the impact of the cold war?

“I still have a letter from a Ukrainian graduate student who lived in the US. He wrote to his friend in Ukraine that the CIA made him translate the book Malaya elektronnaya schetnaya mashyna (Small Computer) by Serhii Lebedev in 1952. Obviously, no Soviet scientist could give a classified book as a gift to a foreigner. That was how the Americans learned about Lebedev’s machine.”

What do you consider the work of your life?

“‘Dnepr,’ the first mass general-purpose computer in Ukraine. In 1957, the Computation Center of the Academy of Sciences of the Ukrainian Soviet Socialist Republic was established, based on Lebedev’s laboratory. My five years at the Center were the most vivid period of my work. The Center’s director Viktor Glushkov suggested that I create a universal control machine, which could be used to control various technological processes.

“At that time I was his deputy for scientific work and headed the department of specialized digital machines. I had to hit the books in order to understand the way different production processes were controlled, and how a machine can replace a human. Having gathered an immense amount of information and learned a number of production processes, I determined the approximate content and characteristics of a general-purpose control machine: memory volume, productivity, etc. The machine needed a device communicating with the object connected to appropriate production equipment.

“The Center’s technical departments worked on creating the machine. It combined many brand new devices: memory on tiny ferrite cores, transistors, etc. The plant ‘Mailbox 62’ producing machines lacked workers and solved the problem in an original way: they employed high school seniors. When we picked up the machine from the plant, we were shocked: the work was done carelessly, it was an utterly flawed product, all connectors were damaged, and most of soldered joints broken. We were pressed for time. Then I gathered the team I worked with and said: ‘The situation on the front-line was even more difficult, but we won. Let’s work as we did there!’ We did it. We soldered all over again, we repaired the connectors... As a result, ‘Dnepr,’ the first model of a general-purpose computer in the USSR, appeared in Ukraine.

“At that time there wasn’t any large-scale computer production in Ukraine. ‘Dnepr’ passed a very serious quality control. Two state committees consisting of 20 specialists gathered to test it. The machine was tested in temperatures of ±40 degress centigrade, its stability and substitutability was examined. On December 9, 1961, the ‘Dnepr’ computer was accepted for mass production.”

Were there any analogues of “Dnepr” at that time?

“Later I learned that the Americans started working on the universal control machine ‘RW300’ a bit earlier. It was created almost simultaneously to ‘Dnepr.’ It was a moment when we almost managed to eliminate the gap between the levels of Soviet and American technology; although it was just one direction of development, it was a very important one.”

How was “Dnepr” received?

“It takes time to recognize something new! The first time I spoke about our intent to create a general-purpose machine was at the all-Soviet conference on computer-aided manufacturing in 1959. I remember one official saying during the discussions: ‘These are just academic whims, cross out of conference resolution the item on creating that machine altogether!’ About six years later ‘Dnepr’ was mass-produced. The head of the Lenin Award commission, the president of the Academy of Sciences of the USSR Mstislav Keldysh told Glushkov: ‘You were ahead of our times, we didn’t understand you and thought such a machine was impossible!’ That is why we never got the award. But demand for this machine, on the part of many enterprises and scientific institutions, demonstrated ‘Dnepr’s’ worth without any doubts.”

What was the “Dnepr’s” fate?

“During the decade from 1961 to 1971 five hundred machines were produced at the Kyiv scientific production association ‘Elektronmash.’ This was a record of industrial longevity; machines usually last up to five years, after which they have to be thoroughly updated. When the flight control center for the joint space flight ‘Soyuz-Apollo,’ needed a computer, they ended up choosing ‘Dnepr.’ Two of these machines controlled a big screen displaying all flight operations, especially the spacecraft docking maneuvers. The remaining machines were used at different industrial and scientific objects. The Kyiv plant ‘Radioprylad’ produced the first ‘Dnepr’ machines. Eventually, a plant building computing and control machines (currently ‘Electronmash’) was built in Kyiv. Thus, by designing ‘Dnepr,’ we spurred the creation of a big computer production plant.

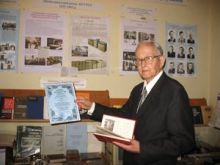

“Today one can see ‘Dnepr’ in the Moscow Polytechnic Museum. An expert commission classified it as a first category monument of science and technology. A second specimen is exhibited in the Benardos Local Lore Museum in the town of Lukh, Ivanovo oblast, my birthplace.”

The Soviet Union, and specifically Ukraine, was on its way to becoming the world leader in terms of computer production. What hindered its development?

“The main reason, in my opinion, is that at one point the country’s authorities lacked self-confidence. In the 1970s, the Academy of Sciences of the USSR decided that we would imitate American computer engineering. These were third generation machines. At that time the US, England, and China started working on fourth generation machines, based on microprocessors. Who needed those giant machines produced in the late 1980s by Soviet plants? That was our doom. It was impossible to make up for the time lost! Then came perestroika — foreign experts visited Ukraine and quickly ‘examined’ our findings. Nobody cared that the most precious ideas were lost. Observing it was painful. Moreover, a number of leading scientists emigrated, mainly to the US.”

How Ukrainian computer science was revived?

“During the Soviet period, as with any planned economy, the development of science was also planned, and with strict control and accountability. Scientists had economic agreements with production units, specific proposals on applications. In the 1970s the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences got over a billion rubles each year. Back then the state built whole academic settlements. Over a thousand young specialists came to the academy every year. Therefore, the Paton Institute of Electric Welding, employing four thousand workers, was known all over the world. The Institute of Cybernetics had two thousand employees, and there were many institutes intensely cooperating with leading Soviet research centers. We were close to another scientific breakthrough. Suddenly, perestroika overthrew everything. In the 1990s, for instance, Ukraine’s budget allotted only 0.3 percent for science, whereas 6-7 percent is the norm.

“The most important thing right now is preparing a new generation of scientists. I remember my childhood, we were obsessed with technology, designing, and inventing — not with making money. Science must be the driving force, as there is no state without science. I know that there are many talented scientists among young people in Ukraine. There are ready, progressive, world-class inventions, but only on paper. The attitude ‘It’s impossible!’ and the lack of state support prevents them from being realized in practice.”