The visit of the delegation of Ukrainian coordinators of the Ukraine-NATO cooperation project, led by NSDC Secretary Yevhen Marchuk, to the Brussels headquarters coincided with Russian Premier Igor Ivanov’s visit there. In both cases one problem was actually at issue: bringing Ukrainian-NATO and Russian- NATO relations into conformity with the times rather than checking their status. The need to do so had become evident even before the September 11 terrorist attack and the latter only emphasized it.

In the case of Russia it was obvious that the Founding Act, signed in 1997, would not provide for a standing rather than onetime cooperation, as happened during the antiterrorist campaign, and that the same applied to other pressing problems, particularly the nonproliferation of the weapons of mass destruction, joint peacekeeping missions, etc. Another obvious thing was the new Russian leadership’s intent to discard Russia’s psychologically traditional opposition and integrate into contemporary global decision-making mechanisms. Vladimir Putin’s efforts in that direction were rewarded late last year when British Prime Minister Tony Blair suggested that NATO and Moscow set up a new body of cooperation based on essentially different principles, involving Russia in the decision- making process with regard to certain issues. Various sources indicate that the traditional mutual distrust is being overcome, hardships notwithstanding; that both sides want equal partnership and it is being gradually implemented, as repeatedly stressed by NATO Secretary General Lord Robertson. An agreement on such a Russian- NATO council is likely to be signed around late May.

No such proposals have ever been addressed to Ukraine for various reasons. On the one hand, this country started being reckoned with as an independent state only comparatively recently. At the time the charter on special partnership with Ukraine had been in effect (it will be five years old this July) and was regarded as a revolutionizing instrument – yet it was basically less important than the one signed with Russia. Ukraine’s role and capacities have never matched those of Russia, and this has also played its role. So far Ukraine has not been able to execute a forestalling maneuver by declaring its intentions for all to hear, probably because such intentions have never been clearly formulated. The confidence in the Ukrainian state has of late been noticeably undermined for various reasons – and not only the cassette scandal (NATO has never commented on it, although the scandal has had its effect). Ukraine’s inconsistent foreign and domestic policies, as evidenced by the problem of arms supplies to Macedonia, have been no help in improving its image as a partner.

“Political will must be shown in the first place,” The Day was told by a diplomat of a country shortly to enter NATO. An equal dialogue is impeded by the absence of any clear political will, consensus between the regime and society, and a NATO-oriented majority in parliament. Logically, this should be a top priority for the new Verkhovna Rada, except that they are too busy trying to solve altogether different problems. Even now it is obvious that the problem of a consolidated and truly effective political stand toward Euro- Atlantic integration is among the most pressing ones – provided one talks not of committees and posts but Ukraine’s strategic prospects.

Put together, this forms a situation in which NATO officials mostly point to good prospects for cooperation within the charter’s framework and partnership for peace. But that is all. Hence the question: Will they invite Ukraine to take part in the NATO summit in Prague to discuss further expansion? And if so, in what capacity?

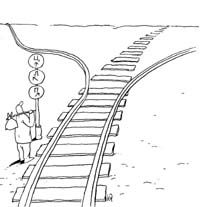

NSDC Secretary Yevhen Marchuk told The Day that there is the risk of ending on the side of the road. However, there is no alternative to gradual Euro-Atlantic integration for the benefit of development and society.