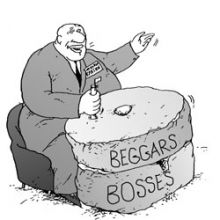

WE’LL HAVE NO PLACE IN EUROPE, UNLESS WE LEARN TO FIRE PEOPLE IN ONE DAY

The Day: Are there many people in Ukraine wishing to acquire property or to work for a private business?

Y. H.: I can answer this with complete accuracy. We have a great many people wishing to have private property, especially in terms of small business. Such views are predominant among the younger generation, less so among the middle aged. Remarkably, over 50% of the population are prepared to work for private businesspeople. An interesting situation took shape in the mid-1990s when attitudes toward private business worsened, but the number of people working in private businesses grew.

In view this, I can confirm that monetary privatization should be carried out in full. In general, there should be nothing one could receive free. An elementary example is our medicine. In the West, health care is provided under very rigid conditions, because they concentrate on treating grave diseases and do not respond to minor problems. But a patient going to a physician with a serious problem is certain of getting help. It’s like a book you give your friend and assume he will never read it. If somebody buys a book, he’ll surely read it, because he wants some return for his money. The same applies to health and property.

I would like to bring to your attention one more thing. Why, for example, don’t we fire one worker or another often? Because they take pity on him. And if our society doesn’t learn how to fire a bad worker the same day, like they do in the civilized world, we’ll never overcome our crisis. It all boils down to the human factor. Often, our organizations keep afloat by intensifying their best experts’ effort. But this potential is not limitless.

NON-CIVIL RATIONALISM

The Day: Is Ukraine’s political system somehow helping to build a civil society?

Y. H.: If we use active criteria, it is not fostering the formation of civil society. Civil society is a network of non-governmental associations where people can fulfill their private or public interests. Compared to 1991, the proportion of people involved in non- governmental is lower. In 1991 it was about 15%; now it’s 12%. Of course, we can refer to 1992 statistics and claim that we have more NGOs now, but most of them exist only on paper and people do not consider themselves involved with them. From this one can conclude that the political system we have formed does not facilitate the development of civil society. On the other hand, it seems safe to assume that there is a legal framework, and any organization can be registered. But, as we see, the legal framework alone is not enough; there have to be other conditions for the development of civil society.

The Day: Perhaps political will. But why should the state need civil society?

Y. H.: I agree that the state does not need it, but civil society is an oversight body over the state.

The Day: What could get us out of this dead end?

Y. H.: The smaller the number of people concerned with elementary physical survival, the better the chance they will seek ways to join various volunteer organizations. But first we must have the base of the middle class expanded — I mean people that will not have to bother about their physical survival all the time. I don’t see any other way to increase the number of people concerned with general social problems. The state has the responsibility to improve the current economic situation. However, it is much more dangerous for it if unorganized socioeconomic protest actions, like the miners’, begin to take on a mass character.

The Day: Is the culture of political choice in Ukraine democratic, totalitarian, authoritarian, or archaic?

Y. H.: I think it is rational. The political culture from the standpoint of electoral behavior is not on such a low level as to be described as archaic, traditional, backward, or irrational. I have carried out a number of polls and studied various factors affecting this political choice. I am convinced that rational choice prevails, one based not on emotion factors, not sentiments, but primarily on rational arguments that can often be wrong, since even such rational argument can be mistaken even if most people accept them. Take the last presidential campaign for example. At the time, most people were emotionally against market economy. We had some supporters of the Left, basically those who wanted to have the old regime back, and a substantial number of undecided voters, most of whom had a negative attitude toward the current regime. Still, most of the undecided ones voted for the current president. Why? Because they were motivated not by emotions but by rational arguments: the president must have accumulated a certain rational experience after five years in office, and maybe he would now do something, and maybe another president would be worse. I think that these are perfectly rational arguments. All this is evidence that our people can overcome their emotional reaction and emotional negativism. Interestingly, more among the younger generation voted for Leonid Kuchma, compared to the older one, as shown by numerous polls. Yet the younger electorate was even more emotionally opposed. This shows that with our young people rational choice was present even more than negative emotional attitudes and even more overcame their negative emotions. Young people have emotionally negative attitudes toward the past five years, but since their interests were not bound up with a communist future, they saw Leonid Kuchma as the only alternative to the Communists. Precisely because of this, I consider that the instinct for rational choice present in our people is a very important element of Ukraine’s political culture. By the way, this is something that cannot be observed in all the developed countries, for emotional choice more often wins out there. Where this rational approach comes from is hard to explain, but the fact remains.

After all, there are quite a few positive aspects about Ukrainian political culture, even ones that cannot be found in the advanced democracies.

The Day: Can you recall something that influenced your world view, and what are your systematic views?

Y. H.: There have been a number of cases making me understand what was happening in this society more deeply. I remember meeting with a supplier (he had a room at the same hotel). It was in 1984, under Chernenko after Andropov, a time when we all knew we had completely dug ourselves into a whole and had no idea where to go next. The man I met at the hotel told me, “This society won’t last long.” Being a professional sociologist, I couldn’t understand. But he had a very simple and effective argument: for money you can get any kind of parts stolen from any given factory and delivered anywhere you want, something no one would have dreamed of ten or so years earlier. What he meant was that the system of secrecy and strict control had disintegrated. And he told me something else even simpler to understand. No one is reporting on anyone to the KGB anymore. That meant no one was any longer afraid of the authorities. And he was absolutely right, for less than three years later, drastic transformations began. I thought about his ideas and considered them for a long time. True, totalitarian society maintains itself on lies, fear, and control. People have to be perpetually lied to and intimidated; once fear goes away, so does totalitarian organization.

Later I realized that this society will take a very long time to change. You know how I realized this? In 1991, I was invited to act as a consultant in a business game performed by the Russian government prior to boosting prices. The younger reformers were modeling the people’s response to precisely such a price jump in terms of public unrest, vandalizing stores, and they were trying to find ways to get through or overcome it. In other words, when embarking on reform, they did not have the least idea what they were doing. They predicted a fivefold price increase and not the hundred times that happened. At the time I tried to explaine that there would be no public unrest, just surprise, and that consumer goods would be still available. And then I understood that it would take these people years to understand mass psychology. And even if we had a young liberally-minded government, this did not mean it was a competent one.

The Day: Unfortunately, we seem to understand this in Ukraine a little late.

Y. H.: Yes, we have also had our young reformers who understood nothing. We all remember that fivefold price increase practiced three times over with regard to our young reformer. What did this have to do with the market economy? And then I also realized that it would take us not ten but with luck thirty years to transition to a new social condition.

The Day: What can we do, considering such mass pessimism?

Y. H.: I have a very simple albeit clear concept of what should be done. Man does not necessarily live by watching all such changes; he has his children and grandchildren. This is a very strong factor. But how can we preserve this economic succession of generations? By saving and handing down the money thus saved. This is the key element of social succession, because everybody knows he will die sooner or later. Meaning that whatever money one can make and save will have to be left in this sinful world. Of course, the point is who will inherit this money. Naturally, the next of kin. If there is none, such money is bequeathed for some socially important projects. So this explains our people’s pessimism: most of them have no savings. Thus I consider the destruction of personal savings in 1992 the greatest social tragedy in Ukraine. Perhaps it could have been avoided. I don’t know, I’m not an economist, but I can judge the consequences. It was the heaviest blow to our people’s psyche, leaving most great pessimists; people started wonder if they could actually leave anything to their heirs. If we can arrange for most people to have savings and people believe in this, this pessimistic view of the situation will change.