Everyone could get acquainted with the work of Mykhailo Boichuk and his pupils from early December onwards. Organizers of the exhibit “Boichukism” gathered artworks from various museums and collections in Mystetskyi Arsenal. Yet some works could not be transported into these halls, for they are… on other walls.

“THEY USED EVEN WALLS FOR WORK”

On a sunny day, we go on an excursion to the National Academy of Fine Arts and Architecture. The pink structure surrounded by chimerical sculptures was built in the late 19th century for a theological seminary, but it has seen all kinds of people in its history, including Sich Riflemen and Denikin’s soldiers. The Nazis organized an employment service here and hoisted a huge flag with a swastika. But the most important event was the moving of the Kyiv Art Institute to this place here in the mid-1920s.

We go upstairs to the second floor. The walls are hung with portraits of the academy’s founders and most prominent professors. This gallery also includes Mykhailo Boichkuk who was one of the founders and later supervised the studio of monumental painting.

“We are always saying that walls teach here because even they were used for work. The true Boichuk began here, and his school, oriented to Byzantium and Europe but based on strong national traditions, was formed here,” Academy Rector Andrii CHEBYKIN says.

“The brand-new professor and his pupils were masters of diverse techniques, but the revival of frescos was their prime concern. Unfortunately, it is Soviet power that cared about paintings and other artworks – not the artists. The paintings in Kharkiv’s Red Factory Theater and at the VUTsVK Peasants Health Center in Odesa were ruined with jackhammers, while pictures on academy studios’ walls were, fortunately, “just” painted over. All this would have been considered lost, if there hadn’t been a fire in the 1970s.

Firemen flooded everything with water, and the “camouflage paint” peeled off, baring some of the 1920s frescoes. The fragments of wall paintings were painted over again, but it was decided to open them in the 1980s. Ostap Kovalchuk, Pro-Rector for Research, says that in the 1980s teachers and students were cleaning the findings from foreign bodies very long and painstakingly. They searched for similar fragments in other places of the academy, but found nothing so far. Yet he does not rule out that some remnants of those paintings may still be hidden under the plasterwork and in other classrooms of this educational institution.

Researchers believe that the pictures were made approximately in 1927-28. It is difficult to conclude whether it is an integrated picture or separate fragments. A hypothesis says that this design was made to “convert” a theological institution into a secular one. But there is a more prosaic explanation: classroom walls served as a training ground for young artists. To be more exact, they honed their skills on caissons – special plastered-up boxes, and classroom walls were “sheets” for their end-of-term projects.

RURAL BYZANTIUM

Boichukists made their paintings in studio No. 250. Artists are still having their classes here. They keep their canvases in the corners and jars with paintbrushes and paint remnants on windowsills, and you can see modern highrises through tree branches out of the window, and a modernistic building of the Academy of Sciences hospital looms close by. Still, academy teachers are convinced: frescoes are the strongest source of inspiration and responsibility.

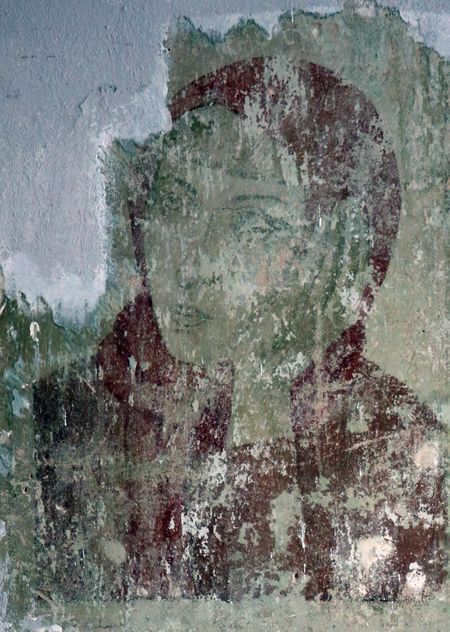

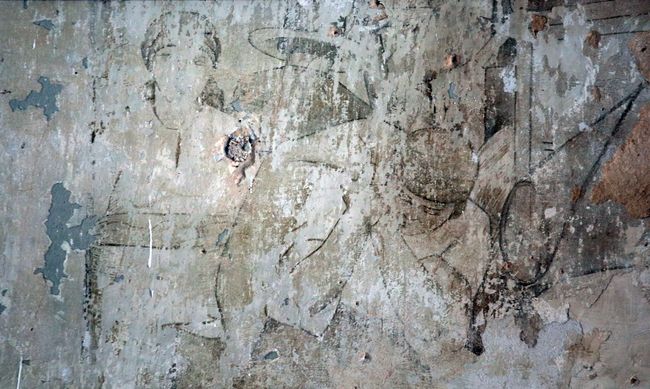

To make out what is depicted on the walls, you should peer into the lines and colored spots for a long time, or listen to an explanation and wonder why you failed to see the obvious. The shapes of women with headscarves on, who work near a thresher, are discernible on the wall adjacent to the windows. Above them, the lower part of a man with a spade is walking somewhere, while the upper one is still whitened. There’s a red flag in one corner and another woman, wearing a typical red headscarf, with a face unusually propped up with the hand – in another. One more portrait, the most conspicuous on this wall, also expresses a symbiosis of Byzantine traditions and a historical national context. It is surrounded by an ornament that refers us directly to the ancient fresco-making tradition represented very well in St. Sophia’s of Kyiv. The portraits are most likely to have been staged. Maybe, heroes were drawn from newspaper front pages rather than from real sitter who ran at the time the risk of being accused of parasitism.

The composition on the wall opposite to the windows is the only identified finding. Kovalchuk says it is “Braking the Hemp,” a work by Okhrim Kravchenko. You can see colored headscarves, a “trend” of that era. The upper part, which depicts the house roof and a lonely tree, has been preserved best. The lower painted layer of the fresco has almost vanished. But the surviving photos of the 1920s helped identify the name and the authorship.

Interestingly, the frescos were not painted down to the floor – they ended about a meter above it. Experts presume that it was done so that future generations do not shield their predecessors’ works with their canvases and feast their eyes on them when finishing their masterpieces.

Portraits are also discernible on one more wall. In the view of researchers, it is worthwhile to go on cleaning up the upper layers – there is a likelihood of finding elements that are symmetric to those found.

A HOLE INSTEAD OF HONOR

The excursion ends in the academy’s basement. There has been a lithographic studio here since the first years of the academy in this building. There are board and sheets with students’ works on the tables. Like windowsills in the previous classrooms, shelves are piled up with paints, solvents, and brushes. Only the new concrete covering and wall slabs remind us that we left the 20th century long ago. Visitors fill the narrow passages and listen attentively to the story of the latest found fragment of a fresco.

The technique of work is rather original – a synthesis of engraving and monumental painting. The lower layer is a dark plasterwork, while the upper one is lighter and grainier in texture. On a small fragment of the monumental decorative picture, you can see the figures of a boy and two girls near a tree. A hole in the wall instead of the face… Ostap Kovalchuk is convinced: the work could not be damaged deliberately in the academy. Maybe, a shelf hung on the plastered wall, or a piece of stucco fell off together with the later layers. The academic considers this “restoration” a symbol of the Soviet government’s attitude to the artistic legacy of Boichukism and Ukrainian art as a whole.

Both the academy’s administration and artists agree that the found paintings should continue to adore the classrooms, for this is the reason why they were created. Yet there is no consensus about the necessity of restoring the findings and continuing the search. Some believe that the cleaned fragments will be lost forever unless they are restored, while others think that it will be unethical to “paint a little more.” Besides, restoration requires funds and specialists, and the classroom will have to be withdrawn from the teaching process. Somebody even said that Soviet plasterwork is the best “preservative” for the still unfound fragments. So is it worthwhile to destroy it if we do not know what to do with the finds? The question remains open so far.