The baptism of Rus’ resulted in a dramatic expansion of the social horizons and the entrance of our forefathers into a social environment of the higher order, Christianity. Since the choice of the Byzantine model is explained by Prince Volodymyr’s obvious bent on totalitarian methods of government, logically his next step had to consist in securing the stability of his realm. In other words, he had to reliably protect the public spirit and public intellect against hazardous foreign influences, using some precursor of the Iron Curtain.

In this sense the creative heritage left by the prophetic brothers Constantine-Cyril and Methodius from Thessalonika, their Slavonic version of The Holy Bible and Slavonic Liturgy, came in quite handy. Traditionally — and as an undeniable axiom — the Greek brothers are treated as national pride, a guarantee of the integrity and ethnic identity of our culture, for here the entire people could understand His Truth, because they were related in the people’s mother tongue. Well, if only the masses could learn the lofty truth that simply!

Everything depends on what we strive to achieve when dealing with this issue: whether we want to justify this feeling of pride or try to honestly analyze precisely what impact such Slavicization of Christianity produced on the collective mentality of our forefathers and what traits it developed and asserted. Whether Constantine and Methodius — or those who dispatched them to Moravia, to be precise — really wanted The Word to become accessible to the Slavic masses and had even transgressed the trilingual dogma (whereby the New Teachings were to be professed using only three sacred languages: Hebrew, Greek, and Latin) to reach this goal. One ought to remember that when deciding matters relating to the official recognition of a new creed and forms of its dissemination, the missionaries had, first and foremost, to reckon with those at the top of the social ladder. And such people had a rather special notion of the language and its functions. Thus it is worth looking more closely at the course events took in Eastern and Central Europe at the time.

POLITICAL ASSIGNMENT

After Charlemagne conquered the powerful empire of the Avars, Slavic independent Slavic principalities expanded or emerged as prototypes of states. To draw them into the orbit of the “civilized world” and prevent aggression from the heathens, Rome and Constantinople set to baptize the Slavic world. Translation of the Bible and the Slavonic Liturgy were to expedite the process, or so Patriarch Photius thought.

The idea of translating the Bible and sermons into “barbarian” languages was not new, all things considered. Even in the early fourth century Bishop Ulfilas [or Wulfila] of the Goths translated the Bible into his native language. In the ninth century, the tradition of delivering sermons in the vernacular was spread by missionaries from Ireland, then referred to as the Holy Island. Of course, Irish monks brought the Good News to the Slavic lands as well. In fact, they seem to have reached as far as Kyiv. The plan conceived by Patriarch Photius consisted in giving Slavonic the holy language status, on a par with the three established ones.

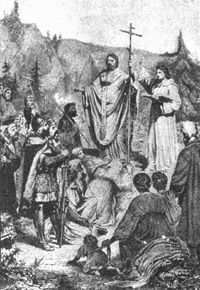

The mission was assigned Constantine, teacher at the then patriarchal school of Constantinople, a gifted scholar versed in ancient languages. He invited his brother Methodius, a former soldier and experienced administrator, to help. In 863, requested by Prince Rostislav of Great Moravia, a Greek mission led by the brothers set off to the Slavic lands (incidentally, subordinated to the Roman Pope at the time).

When adopting Christianity by the Byzantine rite blessed by the Pope, the Moravian princes expected their German neighbors, counts and bishops, would from then on respect them as their equals. Very quickly, however, it transpired that the Byzantine rite was regarded as “lower” than the world level, as at the time the whole West adhered to Latin. In addition, German clergy started accusing Bishop Methodius of Pannonia of professing the Arian heresy, alleging that Christ is connatural, rather than consubstantial with the Father. Feeling deceived, the Moravian princes ordered the Slavic missionaries out of their domains and replaced Constantinople’s “barbaric” variant of Christianity by the universally accepted Latin rite.

Yet the cause the brothers served did not die. Bulgarian rulers, who fought with the Byzantine Empire over the Balkans for almost two centuries, decided to merge with their Slavic subordinates into a single people. This would be best served by sharing the same religion, of course. Moreover, the Bulgars wanted Christianity as a world religion, thus to be recognized by the European states.

Khan Boris adopted the Greek variant of Christianity in 865, but then his son, Prince Simeon, severed contact with the Greeks and embraced Slavic Christianity. He invited Methodism’s disciples, who had been expelled from Moravia, back to his realm and proceeded to lay the foundations of independent Slavic-Bulgarian culture. Unlike Moravian princes, Simeon did not have their inferiority complex; as a Bulgar, he was considered successor to the dynasty of Attila the Hun. Thus, he regarded as upstarts the Byzantine emperors of the Macedonian dynasty sired by Basil I’s former groom.

After receiving a first-rate education at Constantinople, Prince Simeon set himself the goal of creating a new Christian civilization, a Slavic one capable of competing with that of the Greeks. However, after his sudden death the Byzantine emperors, aware of the threat, resorted to severe purges. After almost a century of warfare, Basil II finally routed the First Bulgarian Empire, which in 1018 ceased to exist as a state.

Kyiv Rus’ turned out the successor to the Slavic option of Christianity.

SPIRITUAL ELITE IN RUS’ AND ITS LEVEL

After Prince Volodymyr baptized Rus’, Bulgarian missionaries set off to Kyiv, bringing with them the Slavonic version of the Bible and Liturgy. The Greeks in Byzantium did not mind; on the contrary, they helped the process, thus considering us barbarians unable to master the universally recognized languages.

Petro Skarha, a Jesuit, in his treatise On the Unity of the Church of God..., wrote, “The Greeks have deceived you, oh people of Rus’, because by giving you the divine faith they did not give you the Greek language, forcing you to use Slavonic, so you would never achieve the correct understanding and knowledge...” The experienced polemist thus came to the point: the issue of the Slavonic version of the Bible and Slavonic Liturgy was primarily focused on the level of the Slavic cultural elite. Here, at this starting point, lies the most essential specificity of our Old Rus’ intelligentsia and the specificity of the roots of our spirituality.

Russian philosopher Fedot ov was the first to raise well-justified doubts about the value of Slavonic translations. He wrote that on the face of it Church Slavonic makes the task of Christianization of the people easier, preventing the appearance of a Greek- or Latin-oriented and thus alienated intelligentsia. But at what price? The price was too dear: deviation from the classical tradition.

The Catholic Church persisted in its Latin usage. We might be even surprised by this, because Latin by no means facilitated the promulgation of the new faith. So there must have been something even more important. What?

In the West, a monk had to master Latin in order to read the Holy Scriptures and write his own works. Latin was the magic key to the treasure-trove of world classical culture. Naturally, the Western spiritual elite merged with the World Cultural Flow. Fedotov noted with regret: “We could have read Homer and philosophize with Plato, and returned with the Greek Christian thought to the very currents of the Hellenic spirit, receiving as a gift (the rest would come ‘as a matter of course’) the scholarly tradition of antiquity. Providence ruled differently.”

In poverty-stricken and dirty Paris (Queen Anna Yaroslavna, daughter of Kyiv Prince Yaroslav the Wise complained it was a city inhabited by savages) of the eleventh and twelfth centuries, scholastic debate was in progress, the elevated scholarly style was being polished and universities established. What was happening in our golden-domed Kyiv in the meantime?

The elite of Rus’ was getting everything in translation. Any translation is different from the original text, no matter how skillfully done. Yet the greatest evil is not that translation implies someone’s right to select something to someone’s taste or predilection, but that a certain mental stereotype is developed and asserted, precisely the awareness of one’s own inferiority, an inferiority complex, followed by creative confusion and rejection.

It was thus, with our Kyiv spiritual ancestors fighting Greek dominance, that our elite developed for centuries to come a hatred of the ancient languages and an unbalanced perception of everything foreign, either radical rejection or an unrestrained borrowing verging on parody, just so we could conceal our own inferiority complex.

Some will argue that, unlike the West, our intelligentsia and the rest of the people are close. Indeed, Fedotov wrote, “A monk and a scribe in Old Rus’ were very close to the people, perhaps even too much so. There was no tension between them, which is formed by distancing and which is the only factor capable of giving culture an impetus. The teacher’s condescension should correspond with the pupil’s evolving energy. The ideal of culture must be elevated, hard of access, so as to awaken and strain all the spiritual [cultural] forces.”

What happened instead was a profanation of high truths. Our elite at the time failed to become part of world cultural traditions. Although, several centuries later, History gave it yet another chance, namely the Church Union of Brest. It was a desperate attempt of spiritual elite to join the single Christian World.

Yaroslav the Wise, ascending to the Kyiv throne on rivers of blood, tried to establish his version of the Roman Empire (as had Prince Simeon in Bulgaria). Actually, it was a prototype of the Third Rome. Prince Yaroslav adopted as the holy language artificial Church Slavonic compiled by Constantine, which after the fall of Bulgaria had lost official support. Rus’ could thus acquire a new cultural sphere without losing its independence, and do so forthwith. Thus emerged the Rus’ rite with its holy language and Cyrillic alphabet.

The Slavic Rus’ rite was the basis on which the Polyane Slavic and non-Slavic (including Varangian-Rus’) elements merged into a single whole, a single Rus’ land which also indicated the assertion of foreign Varangian Rus’ in the territory beyond the Dnipro. Until then Rus’ had actually retained a foreign ruling stratum which would now and then collect tribute as a capitation tax or quitrent and would take orders only from the prince, but had nothing to do with the territory. It was now that Rus’ could appear on the world arena as an equal state, albeit with its own specific form of Christianity, separated from Europe by the vernacular.

The far-reaching consequences of this variant of entry to the Socium of the higher order, with a rigid and immediate adjustment of the laws of the new Socium to our national specifics, become apparent even after a brief and superficial comparison to countries that chose a different form: first, studying diligently, then maturation and equal participation in the development of world culture.