Adalbert Erdeli mostly worked in the genres of portrait, landscape, and still life. Critics said that his works “do not burn out.” The Oleksandr Harkusha Publishing House published a book about this outstanding Zakarpattian and dedicated it to the 125th birth anniversary of the painter. The book’s press run is only 200 copies. Currently people are trumpeting about Erdeli and appreciating the importance of his canvases (the prices for his paintings are soaring). But it has turned out only recently that Adalbert Erdeli (A.M. Hryts, 1891-1955) was also a brilliant philosopher, poet, and writer. A brilliant man, a rebel, a nonconformist, he would be disgraced under any despotic power and its servants.

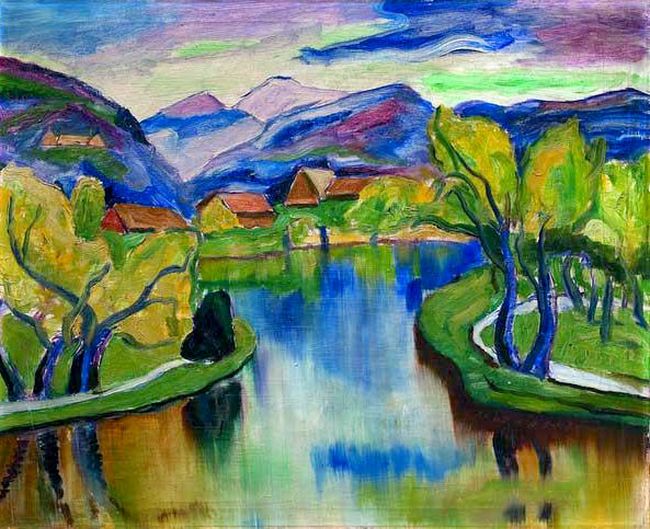

I saw the fullest collection of Erdeli’s works five years ago at Khlibnia Gallery of the National Preserve “Sophia of Kyiv,” where next to the canvases by Yosyp Bokshai his works were on display within the framework of an exhibit that lasted for two months and was dedicated to the 120th birth anniversaries of both artists. There is something about his works that is really blazing. The paint, the color, and the tone are living and breathing, revealing the mood and condition on the canvas. Every stroke is freely shimmering, creating numerous lines which produce a complete image.

Several years ago I received a phone call from a playwright, journalist, and writer Oleksandr Havrosh, on the eve of the premiere of the play Beautiful Summer in Paris, based on his play about Erdeli. This is the first drama work about the great artist. During our interview Havrosh showed me his book Erdeli’s Mystery from the Post Scriptum series. An Uzhhorod married couple Mykhailo and Anzhela Man should be paid their due for their generosity which helped the publication to see the light.

The narration in the thin book is laconic and includes many interesting facts about the author, but it is also attractive because it features Erdeli’s artistic-epistolary works. The only flaw of the publication is the small grayish illustrations which are annoying rather than supplementing the content of this book, which was published in the time of extraordinary possibilities of computer graphics. In spite of that, Erdeli’s Mystery is worth of attention. First of all because it begins with a laconic presentation of 50 facts from Erdeli’s life. For example, “that the artist was born in 1891 under Ukrainian surname Hryts in the village Klymovytsia in Irsha raion, to a many-children family of a village teacher and his German wife Ilona Zeiski. When Adalbert was 10, his father had under the state policy of Magyarization to change his surname from Slavic into Hungarian. In such a way, the Hrytses became Erdelis. The Hungarian word ‘erdeli’ means ‘woodland.’ This was how this area of the Carpathians was called at that time.”

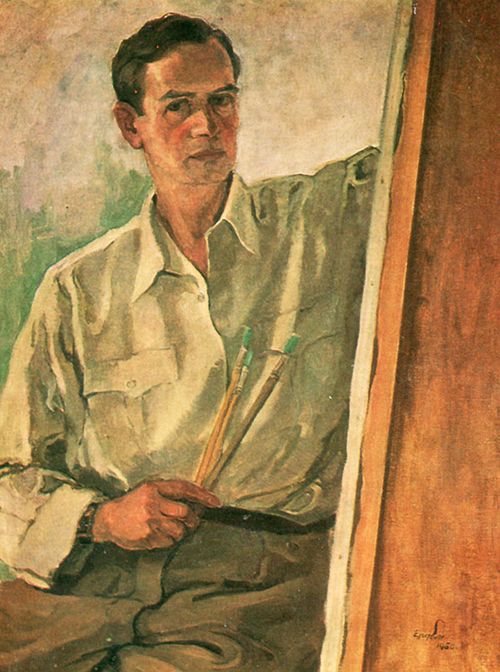

SELF-PORTRAIT, 1950

Erdeli wrote about his origin in his diary: “My stubborn German nature, I’ve inherited from my mom, and Slavic-Hungarian melancholic character, I’ve taken from my dad, when collided, struck sparks of fire in me. I am open, direct, and reliable. I am ready to give up my salvation for a good word, but when I’m hurt, I fight back.” He led a diary till the end of his life. He believed that every line of his notes would be important for researchers some day.

The artist was a polyglot. He knew German, French, Hungarian, Slovak, and Czech. Adalbert Erdeli under the pseudonym Jacks wrote his autobiographical novels, Dimon and Imen in German, he led his personal diaries in Hungarian. According to Petro Skunts, if Erdeli dedicated himself to literature, he would have become a great writer.

Erdeli’s pupils became classical Zakarpattia painters: Ernest Kondratovych, Andrii Kotska, Adalbert Boretsky, Volodymyr Mykyta, Yelyzaveta Kremnytska, Pavlo Bedzir, Ferents Seman, Vasyl Habda, et al. Interestingly, every one of them developed their original manners and none became an epigone of their teacher. Erdeli and Bokshai laid a strong basis for the center of the Zakarpattia painting school. They created “tree and shadow,” and the “golden domes.”

Of course, Havrosh must be paid his due for his detailed professional interview with the greatest Kyiv-based collector of the works by the greatest Zakarpattia artist Mykola Bilousov, an author of 110-page catalog of Erdeli’s works, A Glass Castle among Straw Roofs.

A CARPATHIAN RIVER, THE 1940s

“There is nothing compared to Erdeli’s art,” Bilousov says, “He has no common features with anyone. He has a unique style and powerful talent. Most importantly, he is a national artist. This is very important for Ukraine. Wherever he lived, he came back home, to his native Uzhhorod. He could have stayed in Germany, France, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, or Hungary and live there. But he was drawn back to his homeland. And that was his tragic fate. Because due to historical circumstances, he didn’t find support in his last years. As a result he was partially forgotten as an artist.”

Erdeli confirms this in his notes, why he returned from longtime travel across the foreign land and stayed forever in Zakarpattia: “In spite of everything, I feel that I must stay there, I need to go there, at least for the reason to give a longer candle wick to the small lamp of culture to make it a beacon that would shed more light to the strange romantic atmosphere of my beautiful Verkhovyna. Because every small part of it has become mine, its sun, moon, and stars. Here my eyes started to see, here I started to feel astonishment. My mother gave birth to me from the land of the softwood, my father surrounded me with dense ozone, this is how I woke up in Verkhovyna, near the footstep of the ancient mountains, in native Klymovytsia.”

Owing to the translations from Hungarian by Pavlo Balla we can read the works of Erdeli, philosopher, poet, and writer, in Ukrainian. It should be noted that Havrosh in his book gives a list of annotations of 12 works about Erdeli, which have been published over 60 years. It turns out that in the lifetime of the great artist only once a catalog of one of his solo exhibits saw the light. On September 19, 1955 Erdeli’s heart stopped to beat.