Kobzars, Ukrainian itinerant musicians playing the kobza (traditional Ukrainian eight-stringed lute —Ed.) represent a unique, truly national historical phenomenon. They can be compared to the minstrels at royal and princely courts of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries.

The kobzars, however, served not autocratic rulers but the people. Many were equally adept with the kobza and arms. Among them were courageous scouts and most of them were impassioned propagandists. Their appearance in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was caused mainly by Ukraine’s special historical situation, constant hostilities, and the emergence of the Cossacks with their unique lifestyle. The Ukrainian bards inculcated in the people national pride, awakening them to the notions of freedom and independence.

In their epic compositions kobzars lauded heroic leaders of people’s uprisings and the national liberation movement. Plucking the kobza’s strings, they chanted stories from Ukrainian history to eager folk audiences.

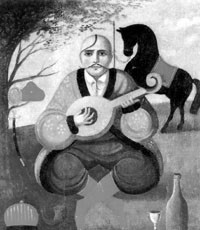

The common folk treated kobzars with utmost respect. This attitude climaxed in the undying image of Cossack Mamai, a skilled warrior and celebrated bandura-playing minstrel. There are cheap popular prints portraying him on museum display, dating from past centuries. Legend has it that he was immune to bullets and steel. His was without doubt an image personifying the invincible Ukrainian spirit and people’s thirst for freedom.

Another kobzar type, altogether different, is that of a blind old man preserving the historical memories of many generations. Such kobzars would walk from one village to the next, guided by young boys. People always made them welcome and listened, enraptured, to their historical narratives in the form of ballads called dumas. Such ballads are first mentioned in the late sixteenth centuries and the first such rendition was recorded about a century later. The first collection of dumas appeared in print in 1819.

Ukrainian kobzars witnessed and took part in historic events over several epochs. Quite often they would join Cossack military campaigns, keeping up morale with their ballads. The Kobzars’ world outlooks largely determined their repertoire and its ideology. Mostly, dumas constituted one of the central folk genres, with emphasis on religious and social dictates. Each such ballad was marked by subtle emotionalism and philosophic depth; most glorified the chivalrous Zaporozhzhian Cossack community.

The bulk of old duma ballads originated from the southern Dnipro River Basin and Black Sea littoral, as evidenced by toponymic studies of this folk poetry. Nevilnychi Plachi (The Lamentations of Slaves) come from even farther to the southeast. They mention Byzantium, the Red Sea, etc. Their authors and performers may have borrowed from the southeast their manner of rendition while being most actively in contact with southeastern Ukrainian minstrels during wars with the Turks and Tatars. Old Ukrainian dumas show a definite intonational affinity for Serbian and Bulgarian folk songs having the same historical basis. At one time this closeness was noted by Ukrainian composer Mykola Lysenko.

Later, during the 1648-54 Cossack Revolution led by Bohdan Khmelnytsky, dumas almost entirely originated in Right Bank Ukraine. Moving from west to east with Cossack troops, kobzars and lirnyky (minstrels playing the Ukrainian version of the lyre) had a major impact on local poetic and musical trends. Meanwhile, testing the Right Bank vocal style as a functional-harmonious way of thinking stabilized there in the early seventeenth century.

The fact that Ukraine was at the crossroads of Eastern and Western cultural trends, especially in the Middle Ages, certainly conditioned the intonational transformation of Ukrainian folk and professional music, particularly the dumas. This influence is clearly traced to and obviously preserved in Ukraine’s Carpathian country music.

An important role in the evolution of the duma was played by the so-called spivuchi bratstva singing brotherhoods uniting kobzars and lirnyky. Such brotherhoods were formed like guilds in the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries to protect the kobzars’ and lirnyky’s interests. As in a guild, each such brotherhood had masters, journeymen, and apprentices (whose number and the term of study were determined by canons), statute, purse, flag, and even a parlance called lebiyska. Apart from that parlance (or secret language), kobzars practiced special musical signals understandable only to the initiated.

Singing brotherhoods or corporations enforced strict regulations on the kobzars and lirnyky and took good care of young minstrels’ training. They were allocated separate quarters or blocks where they could ply their trade. Playing the bandura and singing ballads was allowed only after undergoing a full course of training.

A kobzar was allowed by the brotherhood to take in a pupil only if the had a “service record” of at least ten years. He was then conferred the title of master or “master of the guild.” Some kobzars with teacher status became extremely popular and were given the title of king elder. Every kobzar was initiated in accordance with a certain rite called an odnoklishchyna or vyzvilka. In the course of initiation special attention was paid to how well a young kobzar or lirnyk had learned his craft and also to his moral qualities. In some brotherhoods the ceremony of initiation required the presence of the master who had taught the initiate plus at least three other masters. Such a jury was quite demanding, as evidenced by recorded facts of re-examinations. Failing the latter, the master in charge of the unlucky pupil would be held responsible, sometimes to the extent of expulsion from the guild, as punishment for bad tutelage.

Such corporations discouraged changing teachers, but if this took place pupils would sometimes be made to start the course of training from the beginning. For example, Ostap Veresai, one of the most talented kobzars of the nineteenth century, learned the craft from three teachers, for three years each time. And every teacher tried to convey his own performing technique and tradition.

The singing brotherhoods lost their meaning in the second half of the nineteenth century and practically ceased to exist everywhere.

In other words, the kobzar movement in Ukraine had its rise and fall. As the kobzars’ role in society declined these people turned from fearless minstrels and bards into miserable old men playing their kobzas and wandering in the countryside, living off people’s charity. Naturally, they had to conform to their audiences’ tastes. People wanted to hear merry songs to which they could dance, rather than sad old ballads. Thus the lira (lyre) became more popular than the bandura. Numbers no one wanted to hear were no longer performed. Even worse, such ballads disappeared not only from the repertoire, but also from the singer’s memory.

In the late nineteenth century, Russia’s tsarist government issued a law banning vagabondage. This, of course, affected talented Ukrainian singers and musicians. They were forbidden to perform at fairs or wander the countryside. There are records of numerous cases when the police would seize and crash their banduras, arresting the players. Yet such police brutality did not help as public interest in kobzars increased among the patriotically minded intelligentsia.

Something interesting took place at the turn of the twentieth century as dumas started being increasingly often learned from printed collections of such ballads compiled by folklorists and ethnographers. A kobzar would often ask an educated man to read the text he liked over and over again, until he memorized it. Often, the boy guide would do it.

Dumas’ poetic and musical merits impress even modern audiences. Originally recited by kobzars who took part in Cossack military campaigns, centuries later this genre became part of the professional kobzars’ repertoire.

These ballads are a poetic melodious means of emotionally enhancing the contents and declamatory patriotic character of the text.

The melodious character of such ballads is, to an extent, the result of improvisation, yet it has compositional regularities indicative of professional skill. Poetic exclamations Oh! or Hey! are answered by the chanting arioso-like tune called at the time zaplachka [from the noun plach, weeping, lament]. Pathos-filled interjections are in a way a psychological signal to the listener. They are akin to lamentation. In the melody of the great Ukrainian bard Taras Shevchenko one can often discern precisely such overtones.

With time, the phonograph came to the folklorists’ aid. Its undeniable advantage was that, after listening to a recorded performance time and again, one could perceive very subtle nuances and then write music conveying the recorded rendition with high precision. This was especially important in the case of dumas and kobzars’ improvisations.

Lesia Ukrayinka, the brilliant Ukrainian poetess, was well aware of the difficulties encountered by folklorists, for she herself collected and recorded folk renditions in her native village of Kolodiazhne in Volyn. In 1908, she organized and financed an ethnographic expedition. Composer Filaret Kolessa, Myrhorod schoolteacher Slastion, and Borodai, a devout enthusiast of folk songs, were to take part. They wanted to explore villages in Poltava oblast, looking for kobzars, but Kyiv bureaucrats forbade the expedition. After that the clever Kolessa arranged for a group of kobzars to visit Myrhorod and made several phonograph records of their songs.

The records were meticulously “deciphered” by Kolessa and used as the basis of a fundamental priceless work titled Melodies of Ukrainian Folk Dumas, which appeared in print thanks to Lesia Ukrayinka’s financial support and insistent solicitation at the Shevchenko Scientific Society in Lviv. The poetess was deeply concerned about other Ukrainian ballads still to be recorded. She wrote, “Kobzar melodies are far more interesting than all the tunes kept in ballad stanza; publishing Kobzar melodies will be a new, perhaps the greatest contribution to our national pride...”

While in Yalta, Lesia Ukrayinka made a trip to Sevastopol, and found Hnat Honcharenko, then one of Ukraine’s best kobzars, and brought him to Yalta for a phonograph session. Slastion sent his phonograph from Myrhorod and recording drums had been ordered and supplied from Kyiv and Moscow. The poetess had learned to operate it herself.

That time, in December 1908, Hnat Honcharenko played and sang ballads “About Oleksiy Popovych,” “About a Widow,” “About a Brother and Sister,” “About Truth,” and “About the Parish Priest’s Wife.” 19 recording drums were used. All were sent to Filaret Kolessa in Lviv who deciphered them and included them in the second edition of his Melodies.

Lesia Ukrayinka was very grateful to the composer for working on the Yalta records. “Now we can really say that ‘our song and our thought will not perish but live on.’ You have accomplished a great deal and deserve all possible praise. Thank you!” she wrote.

The twentieth century made corrections in the kobzars’ creativeness. Dumas as a genre lost their previous significance, remaining of purely scholarly interest, being part of the Ukrainian national heritage. However, bandura-playing is becoming increasingly popular. Now the instrument has new capacities, being used to perform most sophisticated compositions by domestic as well as foreign classics. Ukraine’s bandurist cappella is touring the world and, thank God, there are still kobzars singing old and new songs.

The bandura, kobza, and lira continue to resound with the dumas of Ukraine’s past, present, and future. They contain the wisdom of our people. The kobzars have preserved them for us, and it is now up to us to preserve them for the generations to come.