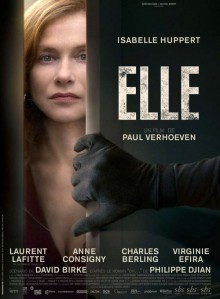

The name of Paul Verhoeven (b. on July 18, 1938. in Amsterdam, the Netherlands) is equally acclaimed in both America and Europe. Total Recall starring Arnold Schwarzenegger, Basic Instinct with Michael Douglas and Sharon Stone (1992) are Hollywood’s classics now. But Europe also remembers him for no less professional Turkish Delight (1973), Soldier of Orange (1977), and Flesh and Blood (1985). What many consider as a new unexpected success is an erotic thriller, Elle (“She”) (France, 2016), starring Isabelle Huppert, that has won two Golden Globe awards.

Paul Verhoeven chaired the main jury at the latest Berlin Film Festival. His meeting with the media and audiences was part of a parallel program, Berlinale Talents.

HOLLAND

Paul, one of your favorite directors, Luis Bunuel, once said that the films that we see between the ages of around 8 and 16 are those that mark our taste in culture in adult life. Were there films that you saw when you were growing up that really made a mark on you and made you want to be director?

“Well, certainly, Bunuel, but that goes really way back to Un Chien Andalou, this short surrealistic film that he did together with Salvador Dali. So, I saw that when I was 16 or something like that, it was an old movie in the Dutch Film Museum. And then, of course, Bunuel’s Belle de Jour, which is probably the closest to the movie I just did – Elle. So, Bunuel is important, and then, of course, many, many others in the beginning when I was not making movies. The more you make movies yourself, the more difficult it is to accept other people, because you are in competition. But when you are not adept director yet, when you can be completely open-minded, you like what you like. So I think when I grew up, when I was a student, I was influenced by David Lean, Alfred Hitchcock, and in effect Sergei Eisenstein – that old group. I am sure, my interest in Hitchcock and studying his movies throughout are preserved until now. And you can see that in many of my films, like Basic Instinct.”

I recently saw one of your early films, called Spetters, about a biker gang in the Netherlands, which has also a rape scene that is more or less similar to Elle. How do you see that film and think about it now?

“I’m fine with that film. But it was a scandal in Holland. I mean, it was bashed by everybody – television, radios, dailies, magazines. Not the public, it was a successful movie financially. For months and even years later, when critics wrote reviews of other movies, they would say ‘Thank God, it is not Spetters.’ It was an important reason for me to flee to the United States. In Europe you are dependent on the money that government committees give you. It is not a capitalist situation, there are no studios. For them I was decadent and perverse and they didn’t want to give me money anymore. It [Spetters] pushed me to go to the United States, for good or bad. I had a great time there, but my life changed a lot.”

AMERICA

You went to Hollywood and in 1987 you had your first big hit, RoboCop. How did you get its script?

“Producer of Orion, Mike Medavoy, sent me the script for RoboCop. I tried to read it and I threw it away because I thought it was completely silly. All the movies I had made in Holland were based on biographies, autobiographies, rarely really completely fictional. I grew up, also because of Dutch mentality, being very much influenced by reality and less so by fiction. And doing a science fiction movie, like RoboCop was, as they said ‘RoboCop – the future of law enforcement,’ for me was like... I could not read even 50 pages, so I threw it away. Then – it was all happening on a holiday with the family – I went for a swim and my wife Martine read the script in the meantime. When I came back, she said ‘I think you have made a mistake here. You should read this script very precisely, because there are things there that I feel will be really very attractive to you.’ I did not follow up immediately, but then after a couple of days, I started to read it with a dictionary, because it was in English, and then I started to see that what convinced me to do the movie; that was ultimately the RoboCop, human being becoming a robot – when he goes back to his house, where he lived as human being, and flashbacks come to him about his wife and the love. When I got to that point in the script, I thought: ‘OK, I know what to do, this is like a nearly religious experience – trying to go back to paradise, only the paradise is lost.’”

Talking about courage and within that sacrifice, I know that you have written a book about Jesus Christ, and there are parallels with your movies where main characters make sacrifice, like in RoboCop.

“Well, I never use the term Jesus Christ, I call him Jesus of Nazareth, I mean, Christ was added later. Yeah, RoboCop for sure has something to do with Jesus, and there is resurrection, I mean, there is crucifixion in the beginning. And when you see that the robot comes to life, it is really resurrection. I mean, interesting enough, when you read the New Testament, you realize that Jesus after the resurrection did not say much anymore, apart from ‘I am hungry, give me fish.’ And Robocop also does not say much, just ‘Thank you for your cooperation.’ (Laughs.) So, I was really inspired by the New Testament. It is my vision of Jesus, of course.”

To what extent was it difficult to work in a new country?

“I was extremely inspired, or perhaps even afraid, by being in a completely new environment, being in the United States. But I felt very free, because I thought: ‘Well, if it does not work out, I can go back to Holland.’ So, when I had an idea I just did it. I think a lot of the things you see in the movie were invented nearly on the set. I did not know exactly what I was doing, I just hoped people would like it that way. That was not really thought out, it was really a lot of improvisation.”

Paul, you directed Sharon Stone in Total Recall and Basic Instinct, you really propelled her to the front of international stardom. How would you explain that you can get someone who up to that point was a fairly routine actress to really step up to the plate and make a performance which lives for all time?

“When we were starting up with Basic Instinct, she came back basically for some play inversion of Total Recall. We talked for a moment about Basic Instinct, then she left, and at that moment that she left, I thought ‘This will be something completely unexpected. This B or C actress, as she was at the time, she is going to be Catherine Tramell. She can do it.’ It took me months and months in effect to convince the producers, the distribution company Tristar, and notably Michael Douglas before they accepted her. And finally they accepted her because everybody else seeing what was written in the script about nudity, all the actresses said they were not going to shoot that.”

COMEBACK

What made you come back to Europe?

“You know, I made a movie called Showgirls. I like that movie still, but a lot of people at the time did not. And so it became really difficult to work in the United States, I would not say I was blacklisted, but it was difficult for me to do normal movies. They trusted me with special effect, so I did Starship Troopers and Hollow Man, but the only thing that they trusted me with, was science fiction, because I was successful with that. I was fed up with science fiction. I wanted to do something about reality more, go back to my Dutch roots. So it was a flight away, I mean, I had to go to continue my career. So, like I fled to the United States basically because of problems in Holland, then I fled back to Europe because of problems in Hollywood. It was a reaction to what happened.”

Does everyday’s shooting bring new challenges? Do you regard it as something exciting when you get up and go to the set, are ready to go, or do you find it exhausting?

“It just feels like getting a day’s work. Even when shooting Basic Instinct, it was not like we were really aware that it would mean anything. I was even amazed we made it to the movies. (Laughs.) I don’t have to say much, I go to the makeup room, we discuss for five minutes in the morning what would be the shots more or less, and then we just go to the set and shoot it. It is much more mundane.”

Regarding Elle, when you were starting to work on this movie, did you expect it would be so huge?

“We were extremely surprised, it was a little bit like a certain gift. We did our work, we felt it was a pleasant job, production was very smooth, and we had fantastic, wonderful French crew and cast. But we never thought it would be that successful. We knew we had made a very strange movie. It wasn’t until it premiered in Cannes and it got this enormous ovation that we realized it was something that interesting.”

POLITICS

Do you think that the film should be political in principle?

“It’s very difficult for an artist to react immediately to what’s happening. So I think you need distance to transcend. Reacting now to the crisis we face with this Mr. Trump from a film point of view, from a screen point of view would be extremely difficult because there is so much happening, and you will be reacting to the news of the day before. I don’t believe in the instant reaction of an artist to politics. The politics of the moment will ultimately be important in the next ten or fifteen years. But there is no obligation, I believe, to do politics in movie. Making it obligatory is wrong.”

Best films about a war are always made after the war is over.

“I have already commented on the United States as a fascist utopia in Starship Troopers.”

CONDITIONAL MOOD

If you had to quit filmmaking, what would you do? Which profession would you choose after that?

“I would do astronomy or painting. Astronomy at the moment is extremely wonderful, with the Hubble telescope, we can see the rest of the Universe, it’s fascinating. You see all these galaxies, and if you really study all these photographs, you see that the galaxy that is this small on the photo, is really also a Milky Way, like our Galaxy. The immensity of what’s there is absolutely fascinating. And I think it’s absolutely fascinating in astronomy now, so you can spend your life on that for sure. I was trained as a mathematician in fact, I wanted to be a painter, but became a filmmaker.”