“Thus passes away the glory of this world,” ancients said, observing something or, more often, somebody who once was on a radiant summit and then ended up with all the rest or even lower. This ancient maxim sounded like a refrain in my mind, when Maya Plisetskaya performed, together with the Imperial Russian Ballet, in Kyiv’s National Opera.

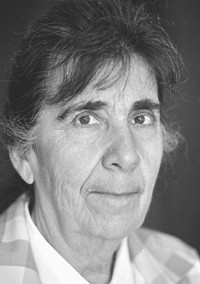

The point is not only in the fact that merciless nature has made out of this once beautiful queen, the queen in every possible sense of the word, petite and helpless onstage, a woman whose once legendary silhouette has preserved almost none of the original, undisturbed by age, lines, or fabulous trajectories of movement she once had (Suffice it to recall the crowd scene from Don Quixote, where her young talent ran riot). Very few could preserve all this at 72, especially under the heavy psychological and physical burdens that fall on the tender shoulders of great ballerinas.

It is also easy to understand that famous people lose with age far more than ordinary mortals do: they take leave of not only health, strength, and beauty, but also of glory, official veneration, the footlights, and mass audiences. You have to be a great stoic to prepare your soul for and reconcile yourself to the final “resignation,” and invent a new way (no longer a style) of life for yourself.

I repeat, the point is not only in this commonplace drama of life which no one can avoid. The question is that Maya Plisetskaya “blessed” with her participation the concert recently shown in Kyiv by the troupe called Imperial Russian Ballet. For the concert program and performance did not meet at all those standards of the choreographic art which Ms. Plisetskaya did and does symbolize. Consider a few impressions of an ordinary, but very interested, spectator.

Let me begin with the fact that the imperials danced to a soundtrack: this often caused rhythmic dissonance between the music and the dance, which an experienced orchestra conductor would never allow. And that soundtrack! Its volume was designed for a stadium hit parade rather than an academic concert of Chopin’s music. Speaking of the dances, the first half struck me with the monotony, even boredom; of the choreography and performance in Prelude a l’apres-midi d’un faune composed of five fully identical and very drawn out pas-de-deux. The eclectic second half was in sharp contrast to the anemic and academic first one. It showed all kinds of things: a tango, cancan, two more classic pas-de-deux, and a kind of “Acquaintance” which could be the gem of any local-talent variety show. All this included different styles, was crude and not of very good taste. I had a lingering suspicion that they had brought a fifth-string ballet troupe to “provincial” Kyiv. For the playbill says the Imperial Ballet has visited many foreign countries, including Japan and France. I cannot imagine that they took there, for example, the primitive Lady in Red as performed by Vytautas Taranda. He proved brilliantly that the lack of technique and sense of proportion can disfigure even the cancan from Orpheus in the Underworld.

The Imperial Russian Ballet spectacle was precisely symbolized by the free programs handed out by a cosmetic firm. It was a mixture of genres: the description of the Imperial Ballet’s global successes, the history of this commercial ballet company, and Maya Plisetskaya’s private life — all well seasoned with cosmetic advertisements. We poor creatures cannot dodge ads even at the opera!

Now comes the main puzzle: why did Maya Plisetskaya, the twentieth century’s prima ballerina (in this writer’s opinion), have to join this imperial show? Only to come onstage for a fleeting moment, remind the audience about herself, and feel its enraptured gaze? But the spectator is a very ungrateful and changeable person who possesses a very short memory and gives thunderous applause only to those who run abreast with the present, not the past, even if the outgoing giants give way to pygmies.