In January of far gone 1862, using the “demonic” phrase of Mikhail Lermontov, the sarcastic poet Dmitry Minaev made a sort of a compliment to the Slavophile efforts of the newspaper Den:

There is no better madrigal for The Day

“Neither day, nor night,

neither darkness, nor light.”

In 1997, in an independent Ukraine, a group of caring people managed to establish a daily publication under the same title. However, to distinguish it from its historical predecessor, and incorporate the essence of the efforts of its modern-day creators, I will choose a different, more fitting madrigal:

Days and nights pass. And with my head in my hands,

I wonder why does not the Apostle of the Truth and Science come?

One who has had even a glance of The Day’s publications, knows that since the moment it was established, the newspaper has been dealing with one of the most important contemporary Ukrainian problems. This is the problem which is found in Shevchenko’s quatrain, even before the publication with the same title appeared, relative to it in terms of names and difference of content.

Let’s pay The Day its due, the creators of this newspaper do not fall into stupor, but continue to “push” the plow and to stimulate other people to work every day for the sake of human, democratic, and other European values. For, as life continues to show, “pitying and grievous sighs” do not change the attitude of Ukrainians either to their own state, which is not yet loved by many, or to themselves, for the better. Regularly counteracting this plight, the newspaper is doing what a periodical publication should do: it gives bright publications, aimed directly at the minds and hearts of its compatriots, and tells about the urgent need for the building of a civic society. Then it goes further, republishing its best materials from previous issues, gradually creating a library of books.

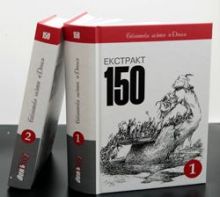

The new two-volume book of The Day’s Library Series bears a telling title, Extract 150, and follows in the previously mentioned tradition. The fact that an intellectual product, successfully prepared by The Day’s team, has not spoiled during nearly 13 years of existence, continues to be useful for society, and shows no inclination to disappear in the rubbish chutes any time soon, relays the importance of its theme. The well-known incident that occurred in Kirovohrad, where Larysa Ivshyna presented the first book of the library, based on articles from the Ukraina Incognita column, is nothing but demonstrative. One of the regional ethnographers, seeking to prove that The Day’s publications are useful for a teacher of history, brought to the presentation a sort of a thick exercise book with cutouts from his favorite publications. The impressed editor, evidently excited, turned this handmade book into a real one. This shows that the materials found in the books are not simply recycled literature, but answer a demand from readers. Indeed, many of The Day’s materials live on, especially in the form of books. Books are important. It is not without reason that the Sacred Writ was simply entitled, The Book.

Fifty years ago, Fyodor Dostoyevsky criticized the Slavophile Den for “terrorism of opinion,” “despotic methods,” lack of skill and desire to take into consideration the times, unchanged dogmatic views, and finally for deliberate ly spreading the “spirit of hostility, fanaticism, and irreconcilability.” The author has intentionally appealed to the reviews of the then Den, because the current Denhas quite an opposite intent, not only in terms of its ideological position, which featured anti-Semitic material or other pamphlets. Whatever one says about “two big differences” or “ungrateful historical parallels,” you may go though the two-volume edition and make sure of this. You will not find any extreme slogans like, “Viva Moscow, let Petersburg perish!” (don’t mix with Mykola Khvyliovy’s slogan “Get away from Moscow!”)

However, there is no need to speak about the book’s flair and intellectual content after the “Word to the readers” by Larysa Ivshyna. Moreover, it would be an ungrateful business. The book speaks about avoiding categorical terms, useful considering the tendency of Ukrainians to go for extremes; that the newspaper should stay above all political wrangles; about seeking points of resistance in home universities, and about cultivating the ideas which could be used on state level, found in The Day’s “experimental area.” It also discusses the photo contest (unfortunately, none of the photos that I have cut out in different years from the newspaper, has not been included in Extract 150; however, it contains caricatures drawn by Anatolii Kazansky that remind that in some ways not only are we succesors of Don Quixot, but Baron Muenchhausen too.). Perhaps most importantly, it covers the stunning warning of James Mace, a pertinent yet under-acknowledged fact, that in reality following the USSR’s collapse, “independence was gained by the USSR,” whose populace leads either virtual or real existence.

Extract 150 is interesting because of the opinions of the personalities it presents. It is a collection of publications by well-known politicians, such as Yevhen Marchuk, Jacek Kuron, widely known philosophers, like Serhii Krymsky, writers and publicists (Lina Kostenko, Yurii Shcherbak, Oxana Pachliovska), noted scholars (James Mace, Stanislav Kulchytsky, Yurii Shapoval), as well as many caring and sympathizing people from overall Ukraine and other countries. Interestingly many of the opinions they have expressed previously are easily projected on the current presidential elections, puzzling parliamentary labyrinths, and the unanswered question: “Why have we found ourselved on the verge of catastrophe instead of prosper?”

At the end of The Day, every inquisitive reader is going to find something for him or herself. I for one was touched by the contemplations of Ivan Dziuba about books in his life (I think that this column should be preserved serve as a present for all book-lovers who read The Day), publications by Volodymyr Panchenko and Vasyl Grossman. I was also moved by the work of Petro Kraliuk regarding “alternative history,” which is no laughing matter, but still ignored by many of our compatriots (on this occasion I will admit that it was a pleasure for me to re-read Extract 150, which I first encountered back in 2003, and still keep as newspaper cutouts in a book).

The Day has indeed persevered, owing to support rendered by “the party of historians.” “Ukraina Incognita” and “History and I” are successfully continued. These columns are interesting, they are written by caring people. That is the reason why Den’s journalism, represented by the two-volumed Extract 150, truly has deep roots, and continues to florish. Those seeking historical concreteness, have precious sources, such as memoirs of Yurii Shcherbak “The Post-Battle Landscape” about the flow of the Orange Revolution, or “Ukraine on H.W. Bush’s Chessboard” on complicated international events connected with Ukraine’s independence, and how Bush betrayed Gorbachev. I advise “Ukraine’s Famine in Foreign Diplomats’ Eyes” by Yurii Shapovalov, a mix of academic and popular history. It is evident from the publications of Igor Chubais and Serhii Vysotsky that even in Moscow and Minsk there are people whose attitude to the most painful pages of Ukrainian past are understanding, without biases and hostility. Along with that the newspaper offers lots of purely educational material: either about the contribution of the Ostroh princes to Ukrainian history; or about the history of the Crimean Tartars, or about the Husite wars, which took place in the Czech Republic, but deeply affected Taras Shevchenko. There is a possibility to familiarize oneself with the work of regional ethnographers covering topics of nationwide importance (Yurii Pshenychny, “The Bullet No. 188. The last path of Valerian Pidmohylny.”)

Indeed, the newspaper, as fulfilling its team’s aspirations, has become a forum for the nation; both through caring contemplations of the best representatives of its elites (such as Lina Kostenko “Ukraine as a victim and factor of the globalization of catastrophes”), and through the letters sent by readers. The publications connected with so-called Anna’s list, through which a 13-year old from Kirovohrad region managed to stir up disturbance among adults with her troubling questions, are of immense value. Naturally, Den takes interest in the girl’s destiny, as is indicated in its publications.

Even those who love to travel will like the book. First and foremost, they won’t be left indifferent by wonderful travel notes “Identity and Modernization” made by Ivshyna. Those who think that journalists have told everything about the Country of Rising Sun are deeply wrong, as the publication presents a “country very close to Ukraine,” which is however “protected by hieroglyphs.”

Specific attention should be paid to the column “Number-One Route” with its illustrated sketches of traveling along the paths of dear Fatherland (as for me, they pleasantly resemble the well-known Proselki by Vasiliy Peskov and forgotten parks by Hryhorii Huseinov): old-time Chyhyryn, Pereiaslav Hhmelnytsky, Skvyra, Nizhyn, Volodymyr Volynsky, Kamianets-Podilsky, Steblev. This is not mere pleasure, but salvation from becoming forgetful. I remembered, in times between stagnation and perestroika, that in the Sofiivka located in the Dnipropetrovsk region the road signs were changed, and the names of population centers and streets were changed as well. At the time an elderly teacher of history, former front line soldier, tried to prove that his native Dolhivka is not Dolgovka, as was written by ignoramuses on the renewed Russian language sign, all in vain. He insisted that the residents of the small village never had debts (which sound like dolg in Russian), simply the village is long (dovhe – in Ukrainian). But at the time nobody paid attention to his just call in the raion newspaper.

The material selected to the two-volume edition is extremely aphoristic. Beyond doubt, one can single out a whole book of winged expressions from this “extract,” and it is the time to use them. These can be found not only in the collections of Klara Gudzyk’s works, for example, her essay about Charles Montesquieu. They are like pearls scattered practically in every article: both classical writers’ quotations and fresh bright notes.

It is significant that both the newspaper, and the books it has produced,unite – if not in life, then on its pages – people with quite different worldviews, religious, national and other characteristics.

Of course, over 1,500 pages could not escape some flaws. In some place the translation from Russian is evidently lame (which is a misfortune for several-language editions). It occurs that in one text the same surname is written differently. In some places Russia was mixed with Rus’. Or Lesia Ukrainka does not hope, but hopelessly expects. In a word, contra spem spero!

However, in the background of the intellectual giant that Den has presented, should one speak about some technical mistakes that a reader can correct without harm to their health? May the too “intelligent” computer not spoil the mood with worthless corrections.