August 24 marks the 27th anniversary of Ukraine’s independence. Back in the early 1990s, there were two trends represented by (a) moderate nomenklatura<P>, people who were aware of the challenges of the times and public moods, and (b) the masses that wanted independence. The latter trend was led by the People’s Movement of Ukraine [popularly known as the Rukh. – Ed.. Oleksandr LAVRYNOVYCH, ex-first deputy chairman of the Rukh, offers his version of what has happened to this political force and why it never became the ruling party. The late dissident, Levko Lukianenko, and Ukraine’s first President Leonid Kravchuk have also voiced their views on the matter at various periods [after the proclamation of national independence].

People’s Movement of Ukraine: My version

By Oleksandr LAVRYNOVYCH

Regrettably, distorting historical facts is characteristic of the Ukrainian political community at large, be it during the election campaign or while on the Olympus, trying to win additional political dividends.

I decided to return to recent events in Ukrainian history for several reasons. One of them was Ivan Drach who had over a number of years repeatedly suggested that I broach the subject of the Rukh and what had actually happened to the movement. Also, there was an increasing number of stories about its history that weren’t true or omitted facts that didn’t fit into the pattern.

After the death of Viacheslav Chornovil in 1999, I wasn’t in the mood of discussing any differences, conflicts or other events that preceded the tragic event. Besides, it didn’t seem to make sense. As years passed, a number of emphases were shifted in recent history and many facts were distorted.

I was among the originators of a Rukh campaign for Viacheslav Chornovil’s candidacy for president of Ukraine in 1991. But then, much to my amazement, a number of Ukrainian political prisoners addressed a letter to the Great Council of Rukh, warning against Chornovil’s candidacy. It was finally approved by a vote of 57 yeas, 30 nays, and 4 abstained, and one of the signatories, Levko Lukianenko, became Chornovil’s competitor during the campaign. The first differences concerning important issues made themselves felt after the landslide (90.32 percent) referendum proclaiming Ukraine’s national independence and electing Leonid Kravchuk as president in the first round (61.59 percent).

The first such difference was the initiative to disband the Supreme Soviet of the Ukrainian SSR, elected in 1990, and to elect independent Ukraine’s first parliament. Viacheslav Chornovil adamantly opposed the initiative and his attitude was a weighty argument. However, early parliamentary elections were assigned, but in 1994, after an abortive no confidence referendum in 1993, with massive strikes and social tensions, the chance to form a qualitatively new political system was lost. The communist party was banned in Ukraine at the time and Rukh was numerically the strongest political force, but it was reinstated in 1993 and by 1994 had formed the largest faction in parliament.

March 1992 saw another event that meaningfully correlated with the first one: Rukh’s third convention during which Leonid Kravchuk declared his support for the movement’s program and proposed it to become the ruling political party. This proposal was approved by the Rukh leadership elected by the second convention in October 1990, but Viacheslav Chornovil took a rigid stand in opposition to the president of Ukraine. It divided the convention delegates and determined the Rukh’s destiny. In order to prevent a rift in the movement, a collective leadership was elected: Ivan Drach, Mykhailo Horyn, and Viacheslav Chornovil.

The third difference that would turn into a public conflict was Rukh’s place in the political system of Ukraine after Chornovil refused to run for president in the second election (summer 1994), stepping down, as it turned out, in favor of Leonid Kuchma. Rukh’s convention in December 1995 formally declared its opposition to the existing regime, but that opposition turned out to be quite peculiar. Two Rukh members became cabinet members and another two headed regional state administrations. The head of state saw to it that Rukh received sponsors. It was a selective opposition and it showed a constructive attitude to the president and cabinet’s suggestions and recommendations, while making no effort to work out a ruling-party-like policy.

In September 1997, the Verkhovna Rada’s Committee on Legal Policy unanimously adopted my initiative of putting impeachment to the vote, charging the president with failing to honor his constitutional obligations (he’d refused to sign the bill on local state administrations after the Verkhovna Rada overrode his veto). It was then Viacheslav Chornovil came out as the president’s outspoken supporter. My initiative was then heard by the Presidium of the Rukh’s Central Leadership and seven out of the 13 members seconded Chornovil’s motion to condemn it. The remaining six supported my stand – that the head of state must act according to the Constitution. After that it became clear that Chornovil would make every effort to secure the sole right to determine the Rukh’s decisions and actions. He started doing just that before long. When it came time to draw up the Rukh’s parliamentary slate, he edited the document prepared by the Central Leadership, proceeding from the results of the rating vote, and asked the counting board to keep it secret. Shortly afterward, he met with the leaders of Rukh constituencies that had nominated me for parliament and asked them to stop supporting his deputy Lavrynovych and turn their attention to another candidate who owned an oil refinery.

Under the circumstances, my second victory in that electoral district sent him ballistic. After the election an emergency Rukh convention was called to order with one item on the agenda: removing Lavrynovych from the leadership. Chornovil had meticulously prepared for the event, but I saw no reason to resist. I clearly saw that the Rukh leader’s line was quickly bringing the organization closer to the inevitable stepping down from the political arena of independent Ukraine.

By the time that convention gathered in 1998, Rukh membership had decreased by approximately ten times. It was a natural and inevitable process. Two months after my retirement, Chornovil visited me at Nyzhnia Oreanda in Crimea where my family was vacationing. He apologized for his actions and said he could see the whole organization cracking apart. He added that he had information to the effect that a coup was being prepared in Rukh and that Yurii Kostenko was to become the new leader. He wanted me to help him fight back.

I said no because I felt deeply offended. Two months later, two-thirds of the Rukh faction at the Verkhovna Rada passed a vote of no confidence against Viacheslav Chornovil as the faction leader. Two-thirds of the Rukh [local] organizations followed suit. What happened then wasn’t a change in the leadership, but a legally sealed rift. That was also the end of my Rukh membership as I refused to join any part of it. Chornovil died [in a suspicious road accident. – Ed.] half a year later. I spoke during the funeral and said that death was a sequel to his political life…

That was the end of the history of the People’s Movement of Ukraine.

Regrettably, unlike Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, and Moldova, where the Popular Fronts and the Sajudis legally ceased to exist, marginal politicians in Ukraine are still using the legally registered title “People’s Movement of Ukraine,” referring to a small body that has long stopped having anything to do with a historical phenomenon that became the driving force in the effort to achieve national independence.

Levko LUKIANENKO: “The 1990s saw Ukraine privatized by gangsters instead of national revival”

(From an interview with Den, Aug. 26, 2011)

What was the situation in and around Ukraine in 1991?

Levko LUKIANENKO: “When national independence was proclaimed in 1991, our People’s Group [the Verkhovna Rada’s faction that campaigned for independence. – Ed.], made up of 124 MPs, could influence the majority in parliament. We proclaimed Ukraine’s independence, but the colonial administration (mostly the executive branch) retained their posts. Those people were raised by Moscow in an anti-Ukrainian, imperial spirit (Moscow ideology was firmly implanted in their minds). Now ideology isn’t a suit one can put on and take off to change. Ideology consists of a number of certain facts that are interpreted in a certain way. Take Ivan Mazepa. Was he a good or bad guy? We know that he was a good guy, but we were constantly told – and we often hear now – that he was an enemy, a traitor. The same is true of Symon Petliura, Stepan Bandera, and others. Such notions were uppermost on the minds of those in power at the time and they made quite an impact on the election campaigns. Whereas the first Verkhovna Rada numbered 124 members of the People’s Rada, the second convocation registered 100, meaning fewer representatives of the national state-building forces. And then the Verkhovna Rada gradually turned into an expressly anti-Ukrainian and entrepreneurial parliament. Those MPs regarded Ukraine from the standpoint of their private material interests, they were turning into racketeers, members of various clans that were appropriating the Ukrainian economy. In other words, instead of national rebirth, we saw Ukraine being privatized by gangsters.”

How would you assess the twenty years of Ukrainian independence in terms of presidencies, starting with the first president, Leonid Kravchuk?

L.L.: “Kravchuk was an apparatchik. He became president as a representative of the communist party. At the time sociopolitical consciousness was such that a nationalist couldn’t become president. There is no denying the fact that Kravchuk is a clever man. Unlike many other communists (then and now), he accepted the idea of [national] independence and quickly took a state-building stand. Kravchuk did a lot to enable Ukraine to proclaim independence. This is a big plus for him and for Ukraine.

“At the same time, either because of the traditional contacts with Russia or because he wasn’t a mature statesman, Kravchuk made a lot of mistakes. For example, he agreed to share the Black Sea Fleet with Russia. Before proclaiming independence, Ukraine adopted a resolution on economic sovereignty that read that everything on its territory, including all river and sea ports, was property of the Ukrainian state. Therefore, sharing the Black Sea Fleet with Russia ran counter to that resolution.

“I think that his second [big] mistake was making Ukraine nuclear free. Despite the G7’s pressure, Ukraine should’ve stood its ground or insisted on more benefits from nuclear disarmament.”

Leonid Kuchma was in power for half the period of national independence (1994-2004). In fact, the current political system was developed during his presidencies, wasn’t it?

L.L.: “Whereas Kravchuk was an apparatchik, Kuchma was one of the ‘red directors’ [a special kind of Soviet managers of large industrial enterprises who by hook or by crook became their de facto proprietors with a distinct authoritarian touch and served as a first class raw material for post-Soviet oligarchs. – Ed.]. Under Kravchuk, managers of industrial enterprises, heads of kolkhozes and state farms began to gain strength, so they brought one of their own to power during the 1994 elections. Needless to say, [President] Kuchma began serving the red directors who wanted to privatize their enterprises. As a result, there began a privatization campaign that eventually turned into one best described as grabadization. All this badly damaged our economic complex. We should’ve used the economic potential left by the Soviet empire and adjust it to the new conditions instead of destroying it. As it was, we kept tearing it apart and creating nothing in its place, doing all this with Kuchma’s blessings and under his supervision.

“Kuchma caused a great deal of damage by introducing a criminal personnel selection system. It was under Kuchma that ministerial posts were put up for sale (something never practiced during Kravchuk’s presidency). It got so, characters with criminal records started receiving important executive positions. That was a typical criminal personnel selection policy. Over the years in office, Kuchma created a system we can’t get over even now. True, he took certain positive steps like having a constitution adopted in 1996. The communists were loath to have it. They dreamed of Ukraine failing as a nation-state and asking Moscow to take it back in its embrace. He managed to overcome their resistance. The hryvnia was also introduced under Kuchma, thus asserting Ukraine’s economic sovereignty.”

Leonid Kuchma remains the only president to have been re-elected, although various dubious techniques were used during the 1999 election campaign. For example, communist leader Petro Symonenko was made the number two presidential candidate, to be confidently defeated by Kuchma in the second round. Did Ukraine stand a chance of changing this system at the time?

“Kuchma had to be removed from power, I mean he shouldn’t have been re-elected. There was a chance. Toward the end of 1998, the national democratic forces decided to back Yevhen Marchuk [as a presidential candidate] and the Republican Party with Viacheslav Chornovil followed suit. I think that if Marchuk became president, it would have been good for Ukraine. He would’ve enforced the supremacy of law – I mean law and order – and this would’ve prevented the oligarch from inflicting such damage on Ukraine.”

***

Levko LUKIANENKO’s commentary for Den(Nov. 28, 2016):

“The Rukh played an important role in the late 1980s as an umbrella organization. Then it became a [political] party and noticeably tended to reach a rapprochement with the second president. In other words, Chornovil decided to collaborate with Leonid Kuchma and this, eventually, badly damaged both Rukh and Ukraine, considering that Rukh could’ve become the best opposition force as an alternative to partocracy. After two commissions were formed to work on the draft constitution – one of the Verkhovna Rada and the other one of Leonid Kuchma – Chornovil joined the Kuchma Commission. The VR Commission wanted a unicameral parliament that would adopt the constitution. The Kuchma Commission insisted on a bicameral parliament and on a referendum that would approve the constitution. The bicameral idea belonged to Chornovil who wanted a federated Ukraine. I’d constantly opposed the federal system because I was sure it would serve Russia’s interest in dividing Ukraine and then grabbing it part by part. Also, if subject to approval by referendum, there would be the risk of an insufficient turnout, considering that the man in the street was already tired of all this. In other words, there would be the risk of failing to adopt the constitution. Then Russia and Poland would have a reason to say that Ukraine isn’t a nation-state.”

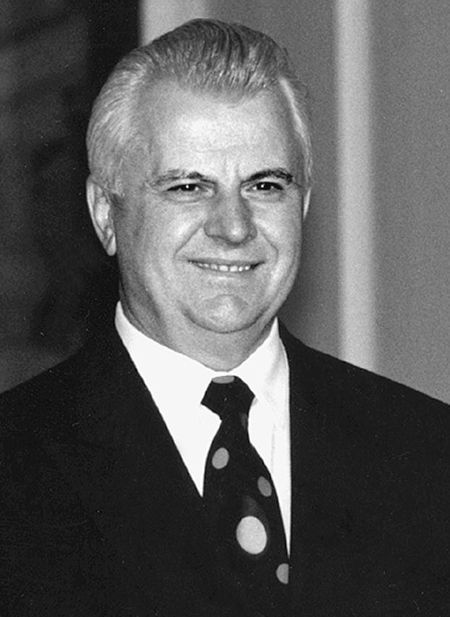

Leonid KRAVCHUK: “Chornovil was offered premiership, but he refused”

Compiled by Ivan KAPSAMUN, The Day

Anastasiia KOROL, Vasyl Stus National University, Donetsk: “What caused the Soviet Union to finally disintegrate? Did it have to do with the Belavezha Accords? What arguments did you bring to Belavezhskaya Pushcha?”

Leonid KRAVCHUK: “What caused its disintegration? The answer is short: the Soviet Union itself. I knew the system like the back of my hand, on all [administrative] levels, ranging from a district party organization to the Central Committee of the CPSU. Let me tell you here and now that it was an artificial system. Broadly speaking, it wasn’t made using some natural historical procedures. It was the will of a group of individuals who had decided to alter the course of history. This is number one. Number two: people who were part of that system weren’t well educated, they were ignoramuses. They knew nothing about the laws of social development or state building. They were there to work out a model the way they saw it. They didn’t care whether or not it met the interests of society. That system kept evolving from 1917 until 1991.

“We [the leaders of Russia, Belarus, and Ukraine. – Ed.] gathered at Belavezhskaya Pushcha and adopted a document that put an end to the Soviet Union. If I went there with just my idea, the opponents would say, ‘We see it differently, let’s put it to the vote.’ And so I went there with a very tangible argument, the entire Ukrainian people. An all-Ukraine referendum was held on December 1 to approve the Declaration of Independence of Ukraine, adopted on August 24, 1991, with Levko Lukianenko among the co-authors. It was approved by 90.32 percent of the population. We held different views on the matter while at Belavezhskaya Pushcha, but we reached a consensus because the vox populi came first.”

Viktoriia HONCHARENKO, Law School, Dnipro: “You were a communist and yet you took a crucial step, banning the Communist Party of Ukraine after the proclamation of national independence. What prompted that decision and how did it happen?”

L.K.: “When the issue of ending the existence of the CPU was raised in 1991, I submitted a document to the Presidium of the Verkhovna Rada. It was put to the vote and then again during a VR sitting. I’d expected the communists to protest, but only one MP, Kotsiuba by name, did. In other words, none of the three and a half million CPU members had the guts to come out in defense of the party. But then Leonid Kuchma came to power and started flirting with the communists, thus paving the way for their return. The communist party was reinstated and the Constitutional Court overrode the resolution on its ban. The Kuchma administration proceeded to use the communists for its purposes.”

Andriana BILA, Taras Shevchenko National University, Kyiv: “Is it true that you offered Viacheslav Chornovil premiership in the early 1990s? What were your relationships with the national patriots like?”

L.K.: “It happened because of my contacts with the People’s Movement of Ukraine. I first had a public televised debate with Rukh’s Myroslav Popovych. It was broadcast live, something incredible at the time, considering that the audiences could hear statements that ran counter to the party line. It was a very interesting debate. Chornovil didn’t take an active part in it. His stand in the matter of the communist regime was expressly radical and he didn’t want to have anything to do with any of its members. I must say that he, as a leader of the Rukh and Helsinki Group, was sufficiently prepared, patriotic-minded, and uncompromising.

“When I attended the Rukh convention, I said, ‘I’m here as President of Ukraine because I need people I can rely upon in my political and state-building endeavors. I’d like to rely upon the will and strength of the People’s Movement [of Ukraine].’ Their reaction varied and some even shouted they wanted nothing to do with a commie. In the end, my proposal was turned down. I also offered Chornovil the prime minister’s seat, but he refused. Later, his associates suggested the post of presidential representative in Lviv oblast. He agreed, but some time later tendered his resignation. Chornovil cuts a very interesting figure. He did more than fight for [the independence of] Ukraine. I always say that one’s desire to struggle for a cause more often than not boils down to waving slogans rather than showing actual accomplishments, unless this desire is complemented by will, knowledge, personal integrity, and above all the people’s will.”

Evelina KOTLIAROVA, Taras Shevchenko National University, Kyiv: “You’re the only president to have agreed to an early presidential election, back in 1994, to put an end to the public protests and political crisis. What did go wrong afterward and why are there no essential reforms in Ukraine?”

L.K.: “In 1991, Ukraine proclaimed a politically independent democracy. But what about the people? They found themselves building a new state. They knew nothing about the new political system, even though they were sufficiently educated, with statistically over 900 high school and college/university graduates per 1,000 residents. However, their knowledge was the exact opposite of what the new Ukraine needed. I agreed to an early election because I didn’t want to hold on to my presidential seat. And then things ran counter to what I thought was needed because we were building a state that didn’t meet the people’s interests but answered those of a political class that was incapable of functioning as a political class of an independent Ukraine. Decisions were made and bills passed that didn’t meet the people’s interests. The situation hasn’t changed since then.”