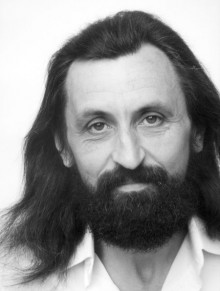

He is often called a Renaissance artist. Anatolii Kazansky’s oeuvre always overstepped the limits of one sphere, for he realized himself as an architect, artist, sculptor, poet, writer, and inventor. He left after himself dozens of folders with his ideas, drawings, and sketches of mechanisms and architectural objects. After his death, Den continued, every day for 10 years, to print the cartoons he had failed to publish. His cartoons are still topical and often appear on the newspaper’s pages, his works illustrate Den’s Library books, and you can scrutinize his surrealist drawings for hours. According to the artist Ihor Lukianchenko, when Kazansky worked at Den, he set a very high standard which all the cartoonists who contribute to this publication have been trying to reach. Vitalii Kniazhansky, a Den journalist, calls him a moral leader of the collective in which his talent and genius were really shaped.

Anatolii was not only a leader, but also the life and soul of the team. His friend Oleksandr Mytnyk, organizer and artistic director of the Odesa-based cartoon cub Line, reminisces about him as follows. “Friends simply called him Kazik. Whenever Kazik and company traveled by Chornomorets, a nighttime Kyiv-Odesa fast train, you could say that other passengers had found themselves in the car by pure chance,” Mytnyk writes in The Great Encyclopedia of Caricature. “April 1 is only tomorrow, but they are already celebrating at full blast instead of sleeping. There’s laugher, noise, and clamor until the very Odesa! Jokes, pranks, and tall stories galore, and Anatolii, the soul of the company, is naturally in the spotlight. And his boon companion Yura Kosobukin – a live wire indeed! Well, they keep merry-making, horsing around, and raising toasts. Anatolii writes and draws something in between the chats and toasts. Then, as the train approaches Odesa near the station Rozdilna, it suddenly turns out that his copybook is filled with a host of bizarre drawings and all kinds of ideas – there are no empty places left. This is the way he worked. He always held a pencil in his hand, while his head beamed a powerful and inspired signal. He drew as easily as he breathed. You couldn’t possibly fancy Kazik painfully nurturing his masterpieces – they seemed to be coming up by chance.”

Kazansky’s easy ways of creation reflected his broad horizons. His cartoons did not examine concrete persons through a magnifying glass – on the contrary, they offered a philosophical reconsideration of time for many years (epochs?) ahead. There were no historical boundaries or “iron curtains” for him. As long ago as 1983 Kazansky was a cofounder of Kyiv cartoonists’ club Archihum. “In the 1980s, television invited Anatolii, me, and several more cartoonists to a youth program. At the time, you had to sit in the studio all day long, waiting for being filmed and interviewed,” says Viktor Kudin, cartoonist, cofounder of Archihum [the original backbone of Archihum consisted of four men only, the four Ks: Kudin, Kazanevsky, Kazansky, and Kosobukin. – Author]. “So, having a cup of tea at that studio, we decided to stage a joint exhibit, and we did so, at the House of the Architect. At the same time we hit upon an idea to found the Archihum club of cartoonists. We used to gather every month to give ourselves an update on caricature and art. Often, when Anatolii and I met, I began to draw a cartoon and he finished it. Then we would send it as a joint product to competitions. We joked: it is humane to make one laugh once, and it is superhumane to do this several times. This is the way we, arch-humanists, were.”

It is no accident that this jocular “arch-humanism” emerges. For Renaissance rested on the ideals of humanism and was oriented to the antique heritage. Kazansky was a philosopher and a thinker, and his cartoons in the newspaper Den seemed to use Socrates’ maieutics in order to help the truth to be born in the head of a reader-interlocutor.

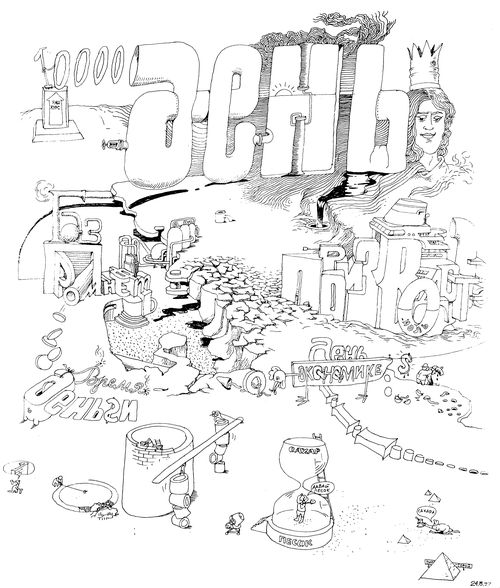

COLLAPSE OF THE USSR

“He was an awfully talented person. Looking at his fingers sent creepers down my spine,” Kudin recalls. “We met back in 1971, when we, students, were upturning virgin lands in Kazakhstan. Anatolii became my best friend. I remember him like this: once we went to see my relatives and lived in a village for a solid week. We would pick mushrooms, mow hay, go fishing, and paint studies. I always recall him in this way. I recently leafed though my archives and found his well-meant caricatures of me. We often played jokes on each other. And his ideas were just incredible – for example, to draw up one alphabet for all or to make a perpetual motion machine. He thought up and drew it, only to find out that a German or a Hungarian scientist had already patented a mechanism like this. It was nearly a disaster to him. But he never ceased to create – he wrote novels, short stories, and poems. Caricature was only one of his facets. He is a Renaissance man. Anatolii Kazansky is the Ukrainian Leonardo da Vinci.”