Danylo Lider believed that theatrical stage was a living creature. He used to smile enigmatically, and whenever he spoke of the “Greater and Lesser Worlds,” the wonder of “transformation” shone through reality.

He worked as chief scenic designer at the National Ivan Franko Theater from 1965 and designed a total of about 150 productions on various famed stages. Among them are such masterpieces of world scenography as King Lear, Yaroslav the Wise, Macbeth, The Cherry Orchard, Uncle Vanya, Tevie-Tevel, and others. Possessing the magical gift of a pedagogue, he educated several generations of Ukrainian set designers, artists, and stage directors. “A pupil of Lider” sounds like a password of trust. A year before Lider’s birth, Kyiv University graduate Mikhail Bulgakov signed the faculty oath that said: “I promise never to compromise the honor of the guild in all my lifetime.” Great Kyivites knew how to keep their word.

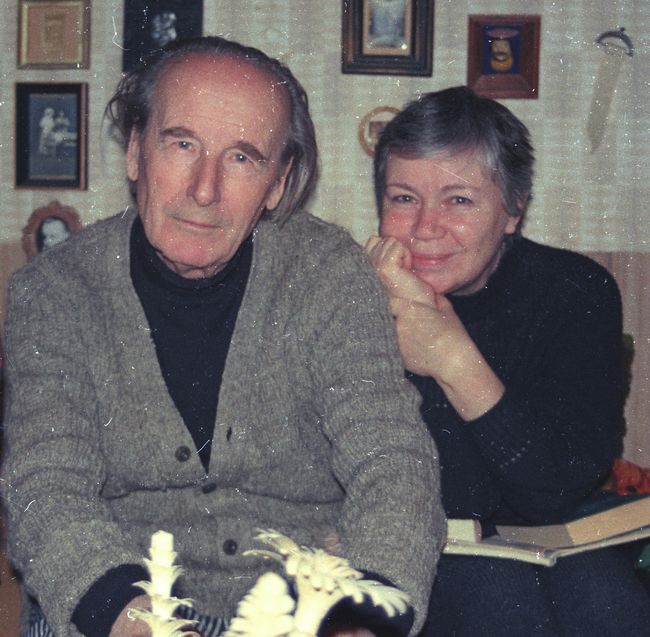

Kira Pitoieva, a research associate at the Mikhail Bulgakov Literary and Memorial Museum, was Danylo Lider’s wife, like-minded person, and closest friend.

THEATER IN A BOX

Ms. Pitoieva, what kind of a relationship was there between Danylo Lider and the Bulgakov Museum?

“I would say he spiritually cared about the establishment of the museum. He was deeply interested in and tested his new ideas on it. The museum was forming its concept before his very eyes, and his role became still more concrete later. When the museum opened its exposition, it began holding various events referred to as ‘measures’ in the Soviet era and as ‘fests’ today.

“At one of those fests, knowing Lider’s creative nature, I persuaded him to mull over the play The Days of the Turbins. He took it up as a scenic designer. I would call what he did a presentation of the future production to the ‘artistic board’ [in fact a form of censorship in the USSR. – Ed.]. When word went around that Lider would show up in the museum, this attracted much more people than the ‘artistic board session.’ What he devised stunned me personally, not to mention all the others.

“A scale model was set up – there were some interior scenes on the ramp, which included a table with some objects, a floor clock, chairs, a small sofa, and, as always in a theatrical scale model, figures of the Turbins and guests. And there were many soldiers’ overcoats on the sides and in the background. Those overcoats were without heads! Headless people were moving en masse and coming absolutely unhindered into the interior. In other words, they behaved brazenly enough to get into the House.

“The sensation that the mass of soldiers is getting implanted into life created an unbelievably strong impression. But, knowing Lider’s theory of conflict, I expected to see not only this force, but also the opposite one. And the performance affirmed that there are always two forces in life. One, very large and active, is soldiers. The other, extremely weak, is the one we would all like to believe will eventually win. This force was Lariosik, a cousin from Zhytomyr. When all got together in the finale, soldiers disappeared and Lariosik proposed his famous toast. In general, as it always happens at an artistic board meeting, there was nothing to discuss.

“Many theaters are putting on The Days of the Turbins now, but nobody has ever suggested a solution like this. We do have headless soldiers who get implanted in our interiors, but Lariosiks are not winning so far. Only we are rallying together. It is clear that the mass was and will always be headless in any war. But it is also a biblical maxim that people tend to get together and weakness will turn into strength. And what aroused Lider’s interest was not the fact that soldiers walk but the fact that they are opposed by the weakness that wins. An eternal theme, of course.

“In 1999 we held a soiree, ‘Three Masters: Pushkin, Bulgakov, Lider,’ as part of Pushkin Days. So he and I made, on a parity basis now, put on a scale model box production of Bulgakov’s Last Days (Pushkin). This grandiose multilayered extravaganza was extremely important to me because I thus implemented one of my ideas with Lider’s approval and assistance. The idea was that nobody sits still, everybody is on their feet, on a rotating circle, people form a ring, all the pictures turn over and form Voland’s ball. And, in the foreground, stands the figure of an unknown with a bauta (Venetian mask of death) on from Meyerhold’s production – the precursor of Voland in the theater. And, surely, Lider wouldn’t have been Lider if he hadn’t finished the performance in his own way. Bulgakov’s play ends with the repentance of Bitkov, with Pushkin’s coffin being carried, and the storm howling. In Lider’s concept, the finale expresses the idea of the victory of light which gradually flows to the auditorium – the person is dead but his light remains with us.

“This strong impression prompted me to hit upon the idea of showing my research subject ‘Bulgakov’s Dramaturgy’ as a series of scale model box productions. Later on, all of Bulgakov’s plays as well as Theatrical Novel were put on in this ‘home theater in the box.’ All this drew capacity audiences, and I was pleased very much to see both Lider’s and my students – set designers and theater experts, respectively.”

CRAVING FOR SPACE

Does the “Order of Lider” still exist?

“It does, judging by the way his disciples responded to the idea of staging a big exhibit in his honor – it was enough to call his name. What still unites all of us is a unique, magical, and unsolved mystery. Lider posed this mystery even to me, although I watched him as closely as nobody else did for 32 years.

“The secret still remains – so many talents related to art. The talent of a set designer and a stage director. The talent of a painter – he was a full-fledged painter by education. The talent of an extremely rich imagination. Another talent was to crave for space – the latter was limited by the stage, but he always jumped off the limits, which he excellently showed in Tevie-Tevel. The talent of a philosopher in art – he knew the philosophical truths of being. I wouldn’t say he read much, oddly enough. But if he read something, he did it ‘slowly,’ understanding everything. Lucretius’ De rerum natura was his favorite book. He was keen on ancient authors and found it easy to grasp Vitruvius. And he could say the things about Leonardo da Vinci’s drawings that you won’t find in high-brow books. He had a surprising feature – whenever he entered a museum or an exhibit, a crowd gathered around him in 10 minutes. He knew how to attract people. He would look at a picture silently, and people would ask: ‘Please tell me, for you seem to be in the know…’ And when he was beginning to speak, all those in the hall were coming up to him. I saw the reaction – when he spoke, people stood spellbound.

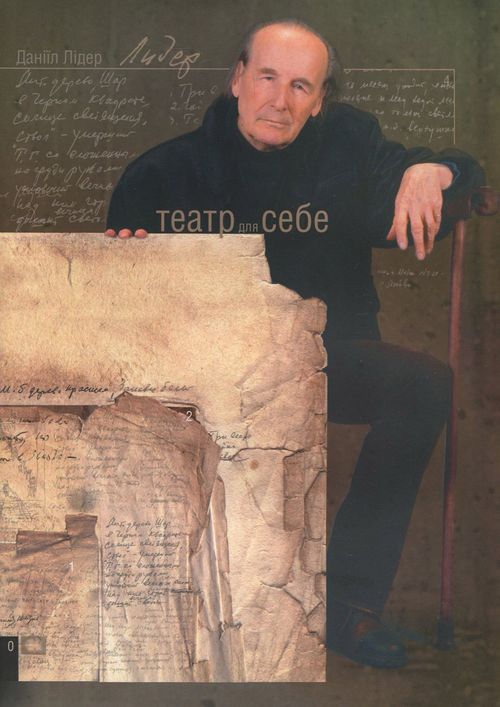

“His pupils were not only those who learned scenography from him. Any people consider Lider their guru thanks to the book Theater for Myself which Olha Ostroverkh and Serhii Masloboishchykov compiled on the basis of his major theoretical works. On the one hand, the magnitude of his personality is obvious in the way he tells, foresees, and tackles problems. On the other, it has a practically invaluable article, ‘The Technology of a Concept.’ It is the most difficult thing in the world to understand where the concept comes from. Everybody wants to know the first impulse – why was it suddenly born? And Lider dared to try to help people reach the level of reflections that can produce an idea. He called it ‘talk-ins,’ he could talk on the subject all the time – sleeping and awake, with me and with those who were with him. He could also talk it over with himself. And what is ‘artist by himself’? He drew all the time. As Masloboishchykov reminisced, Lider used to say: ‘If I were not doodling with a pencil, nothing would spring out of me.’ His conversations, reflections, and sketches formed a grandiose field that comprised an idea. In ‘The Technology of a Concept’ he clearly explained what he would advise an artist to do in order to see a flash of inspiration. And, as he himself constantly dealt with this, these reflections were of benefit to many. Lider had a surprising ability to convey verbally what is impossible to tell. I like Theater for Myself very much because it is in fact for us. It has done very simple wordings which can trigger deep thoughts. You can explain everything in simple words, but only if this has passed through you. Lider spoke very simply. He was a true teacher of life.”

Is it true that many who recall Lider say that he influenced their system of values?

“This question is connected with the reflections on what a scenic designer leaves behind. The theater leaves a myth. Let me get back to The Days of the Turbins – people can’t understand the beauty of the play because they were not present at the performance. Those who were present knew which way the wind was blowing. Today, 80 years on, it is impossible to grasp the play, for you can’t feel the time amply, you can only understand theoretically that time and the people who lived then. In short, the idea is in the auditorium – it is the active part of the performance. But what if it isn’t there? Lider quit the Ivan Franko Theater in 1990 after the premiere of Tevie-Tevel. This production was put on until Bohdan Stupka died, for it carried the idea, and has never been staged since then. And there has been no Lider at the theater for almost 30 years.

“What is left behind? Legends and drawings, but they are of no use for the people who don’t know much about the theater. The point is that a drawing is static, while the theater means movement and, moreover, interaction between movement and the space illuminated with special theatrical light. It is very difficult to speak of the theater, but Lider saw to it by the very nature of his talent that something should be left behind after him. The legend was confirmed by his theoretical works and drawings.”

Which of the main questions did Lider help you find the answer to?

“To the question: what are we living for? How can we learn what we were born for? How can we learn to do things better than the others?”

A MAN WITH A WORLD INSIDE

Danylo Lider wrote an article with a surprising title – “My Favorite Playwright is Nature.”

“Lider used to say: ‘There will be no success if something comes from above. Things should come from below – like the weak grass that breaks though asphalt.’ I saw him stop to look at every grass of this kind. You can’t imagine what he felt when a big old tree was cut down on the corner of Andriivsky Uzviz. He and I laid flowers at that stump for a long time. He could not bear it: ‘They killed such a nice old one.’ Everything was a living creature for him. He called birds and trees with human names. He called a dog ‘teenager.’

DANYLO LIDER AND KIRA PITOIEVA LIVED TOGETHER FOR 32 YEARS. IN THE WORDS OF PITOIEVA, “LIDER WAS OF A SURPRISING NATURE: ANGEL AT HOME AND DICTATOR AT THE THEATER”

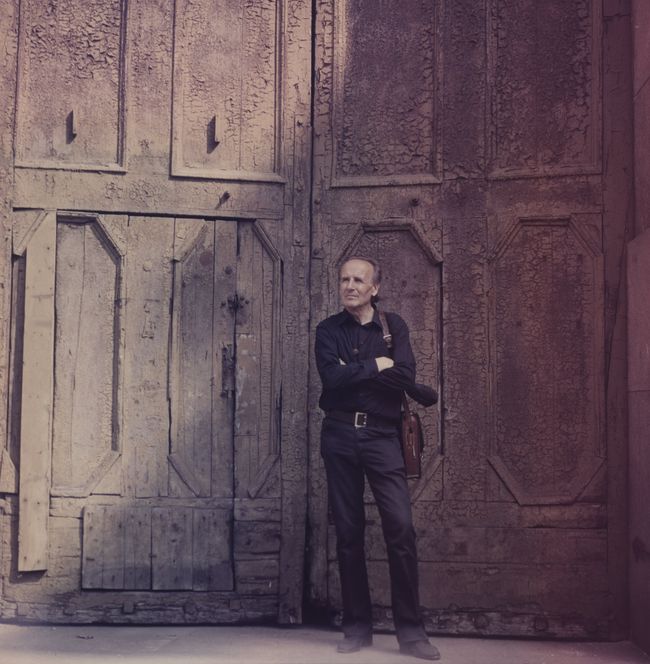

“And he was called ‘Iron Lider’ at the theater. He was of an absolutely strange nature: angel at home and dictator at the theater. But his dictatorship spoke in a very low voice: you could only hear him in a dead silence. At first, when he moved to Kyiv, he was called Davyl [“one who suppressed” in Ukrainian. – Ed.]. He was a very quiet handsome man who smiled so shyly, but if you only tried to give him a piece of advice… I only wondered how he managed to combine weakness and strength. His weakness was endless doubts: ‘And why should the stage director accept my concept? He has a different idea, and he is not obliged to…’ But, on the other hand, he was an iron bar that remained unbent until the last day. He was a man with a world inside.”

There must have also been many funny moments in living with a person like this…

“He was really very funny sometimes in everyday life situations. He once brought his ‘hallmark bag’ from Poland, and he carried it not over the shoulder, like everybody did, but on the neck. So he was often mistaken for a bus conductor – passengers passed money to him, he took it but didn’t know what to do.

“In Chelyabinsk, he had a garment, a coat of sorts, which he called ‘pea jacket.’ He always wiped paintbrushes with it, leaving the marks of paints. After his departure, Liders’ pea jacket was in fashion there – people wore it in spite of paint stains. And in Kyiv Lider wore a quilted coat popularly known as ‘zonka’ [a derivative of ‘zone,’ i.e. prison camp, in Ukrainian. – Ed.]. It was made from the folding-bed cloth, for you couldn’t buy much at the time. But it was called ‘professorka’ at the institute because Professor Lider wore it, and it looked very well on him. When Liubimov brought his theater to Kyiv, I sewed a laundry tag on this ‘zonka.’ There is a photograph of Lider standing wearing the ‘zonka’ with a tag on it and Liubimov donning a gorgeous suit with a white necktie.

“When Lider and I were going to an anniversary soiree at the Franko Theater, I persuaded him to dress well: a black suit, a necktie, and marvelous Spanish shoes – all this suited him very much. As we approached the theater, theater-goers and staff came running to see him. He looked so handsome in a suit with a necktie, those shoes, and without a bag on the neck. And the theater people began to applaud him!

“He was madly handsome – with manly beauty. Mykola Rapai was right to call him preacher. A high forehead, an aquiline nose, an expressive tragic face. He was zealous in work – I called him Savonarola. Girl students would fall in love with him even when he was 80. A handsome gentleman, a sage.”

Please tell me how you met. And how did you manage to form your family-based artistic union?

“When I was recently showing my colleagues the photos of Lider at the time of our acquaintance, they asked me: ‘Weren’t you afraid to meet a man like this?’ Yes, I was terribly afraid, but I was madly in love with him. I was absolutely prepared to meet him. I had seen his productions that struck me. So when we met, I was in no way surprised that it was he because only a person like this could do those productions. I was a set designer aged 31, ran a personal column in a magazine, published a lot, gave lectures, and had a name in the theatrical world. I thought that if I rose to this height, I would not hold out and fall down. Of course, it is both ravishing and unbelievably difficult to stay beside such a talented person because you always wish to come closer to him at least in some way.

“And I decided, in my womanly way, to see to it that everyday life problems should not make me forget that a genius was beside me. And he was saying that the daily routine itself involved one into the artistic process. What more did I need if I had a guru like this? It took me very much time to do my work, which won his respect. I remember sitting for days and nights when I worked on the Bulgakov museum concept, but this raised no misunderstanding in him – on the contrary, he kept on saying: ‘Sit on, please!’ So we eventually decided to discuss things before doing them.

“And when I devised the concept of the museum, it was, of course, ascribed to Lider. Oleg Yefremov was the first to say: ‘I see the hand of a master!’ And I considered it as the highest praise. But our people knew this. Roman Viktiuk said to us from the stage at the anniversary soiree: ‘Here is a couple – one is Lider, and the other has devised a museum worthy of Lider!’ And Roman Balayan said after watching the Pushkin production: ‘I knew everything, but we can only envy the way they did it together.’ It is happiness to meet a person like this. And it is a lifetime gift to do art together. Life finished after Lider’s death, but then I controlled myself – owing to his school again. For he used to say: ‘What’s the use of living without smiling and rejoicing?’

“He was absolutely open, like a child, without any stereotypes. This is why he did not read much. He was writing his book inside himself – about life. And Lider knew what life was and what he was. The proof of this is the sense of dignity he possessed. I never saw him bent and suppliant. I often saw a picture like this: he looks at his sketch and says: ‘A nice job indeed!’ It is about himself, for he liked what he was doing. He went a long road. He knew the price and worth of life and people. He lived through everything in 85 years – sufferings, joys, ups and downs, recognition, and love of his pupils. He lived a fine life!”