I know Ivan Tsikhotskyi, a teacher at the Lviv National Ivan Franko University, thanks to a course of the modern Ukrainian language. Delivering lectures, he was always making historical comments that explained some specific linguistic phenomena. I could not even guess that Tsikhotskyi had collected an impressive library, and not only this. But once I came to know, I wanted to see everything with my own eyes.

Ivan invites me to his house in Korotka Storona, in the center of Busk, Lviv oblast. I seem to be entering a museum – the door and double-glazed windows are perhaps the only new things. All the rest is either from a collection or bears the memory of family generations, for example, a bulky walnut table brought from great-grandfather’s house. The collector confesses that his hobby is a “mixture of childhood-time irresistible love of collection, the self-willed piling-up of things, and a great dream.”

BUSK’S TITLES

Inside the house, there are some miniatures of Galician life, such as, for example, a huge trunk into which you can put half an estate or the dowry of a bride. I saw even Trypillia finds from the lower layers of earth.

Archeological excavations in Busk and on its outskirts revealed remnants of weapons and household items made from clay, silicon, glass, copper, and iron. These items – a sharpened Trypilla sickle, a thin spade, and a flat hammer – can now easily fit the palm of a hand. No less surprising is an arrow tip as long as a finger.

“Sometimes you unexpectedly find these artifacts in your vegetable garden,” Tsikhotskyi says. Many sights in this area remained as heritage of the capital of the chronicle-mentioned tribe of the Buzhans (8th-9th centuries), the capital of an appanage principality (11th-12th centuries), a starostwo center in Belz Voivodeship of the Polish Kingdom (15th-18th centuries), and the unofficial capital of the Baden Republic (late 19th century). All of these “titles” refer to Busk, first mentioned in chronicles in 1097, although in reality the town was founded in the 5th-6th centuries.

RARITY KEYS

The kitchen shows an array of clay jugs for different purposes with or without patterns, of earthy or brown color, and a milk bottle. Next to it is an Austrian vessel of the color of soaked laundry soap, in which wine or oil used to be kept.

I pass to the study room through the antechamber with a 1920s-1930s chandelier. In the center is a restored table which once belonged to a Jewish merchant. On one side, the keys Tsikhovskyi has been collecting since he was a child “open” various expositions. One looks more chimerical than another. Next to this are sort of pictures made of street signs in the Ukrainian language of the Polish and Austrian period and of the glossy tables pages of the Dniester firm’s insurance policy. On the other side is an unbreakable wall of book spines. All the books stand closely to each other and form the room’s “intelligent space” – also intelligent because it harbors theological knowledge in the old 17th-century books.

A GOSPEL RESCUED FROM FIRE

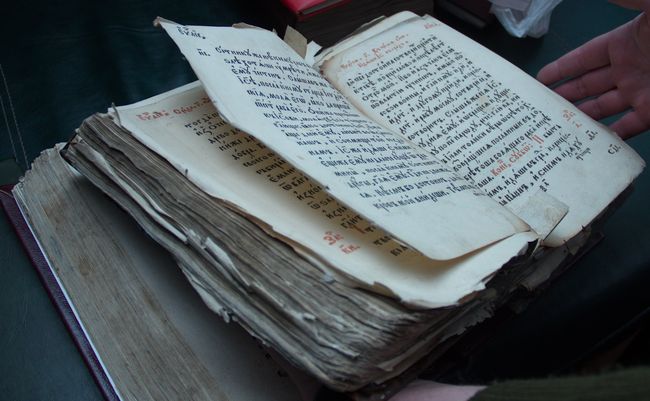

Old printed books are religious publications intended to be used in church. We come to know about this in the notes on pages, as we do about when, from whom, and for how much they were bought. The oldest and perhaps the most valuable book in the collection is the Lviv Octoechos of 1643 and the latest is the Pochaiv Flowery Triodion of 1787. Among other books are Menologies, Anthologions, Festal Triodions and Songs, Service Books, Gospels, and Psalters of various years and editions. Most of the books come from the Lviv and Pochaiv print shops, and there are a few from the Kyivan Cave Monastery and Moscow.

Every book is informative. Incidentally, a true connoisseur will not have to make much effort to “ask” one book or another. You can learn how old a book is even if the title sheet has not survived. There were several systems of data encoding. The filigree, the prototype of the modern “watermark,” can provide information on the date and place of printing the book as well as on the additional parameters of paper. You may only need catalogues of paper and filigrees. The author usually indicated the year on the engravings.

A lot could have happened to a book in several hundred years! You can see how the old printed book has traveled in time by the way it looks. When pages were worn out too much, one had to rewrite the lost content by hand so that the book could be used again. It also happened that a book got into a fire, as did the Lviv Gospel of 1704. It happened somewhere in the 18th century, Ivan says. A deacon saved the book: he stitched up the inner books, stuck on the beginning, and restored the binding. Thanks to a careful attitude, paper was preserved well, and engravings were not damaged.

A non-restored book looks like a big piece of coal: the inner book has crumbled, and the “bowels” – a small wooden board with a rounded edge – stick out of the skin that covers the binding. Numerous touches to this book’s pages have erased the letters, although the color of capital letters remained bright – the mixture of cinnabar, ochre, and red lead managed to stand the test of time. In some places, pages became sharp on the margins and deeply dented, as if it were a saw.

ACCORDING TO GUTTENBERG’S RECIPE

Due to the high cost of a printed book, far from everybody could afford to have one. Nevertheless, the owner, usually a theologian, had to use one continuously. Candle wax dripped onto the paper, leaving brown “scarves” on it, which made some letters invisible to the reader. The paper was made according to Johann Gutenberg’s recipe – all kinds of rags were shredded by means of a special device and then pressed. This made the paper as rigid as cardboard. Ukrainians quickly mastered new technologies. “It was faster than now,” Tsikhotskyi adds. “It wasn’t necessary to patent inventions at the time. So this promoted their rapid proliferation.”

“Each of the 20 books is very special to me. Each of them uncovers a certain layer of history – like this Gospel that belonged to a Carpathian theologian. On one of the pages, he wrote about an earthquake with a graphite pencil. This natural cataclysm really occurred!” the collector assures me.

THE HISTORY OF LVIV BREWERS – IN BOTTLES

Ivan is most willing to speak about collection bottles for alcoholic drinks, for their number grows in a geometric progression. He had to give some to the local history museum due to shortage of space.

Formerly, every brewery made its own brand-name bottle and applied an engraving, not a label, to it. What is more, the bottle was periodically redesigned. The glass collection shows what changes in form bottles underwent in Galicia and Poland. The shelf devoted to the Baden Brewery in Busk reflects changes in the 30-40 years of work. There are about 20 varieties of bottles made by the Lviv Joint-Stock Company of Brewers, with an anchor etched on the glass, in the collection – it is more than on the Museum of Lviv Breweries or in the Museum of Glass! Ivan takes a lesser interest in the vodkas and fruit liqueurs produced by the Baczewski family – he usually swaps them with other collectors. Nevertheless, Baczewski carafes occupy the entire lower shelf. The thematic shelf is complemented with German prewar 50-mililiter “shoes.” The collection includes a few soda bottles – shaped like those for beer but transparent.

Two shelves higher, Ivan placed, as he says, “the sediment trap of Soviet bottles.” It comprises several Transcarpathian half-liter “Schoenborns” and a few bottles that remind me of those for fizzy wines. They found themselves in the “sediment trap” because of “too modern looks.” Well, even the brave soldier Schweik couldn’t help getting lost among so many bottles.