“True art is not the ‘isms’ of Paris, Rome, or Berlin, such as cubism, futurism, or expressionism. It is the need of the soul to express itself and show its inner world which materializes by means of paints or pencil within the framework of three main problems of painting: line, form, and color,” artist Hryhorii Smolsky (1893-1985) wrote in the foreword to the catalogue of the 1937 Lviv-based Exhibit of Watercolor, Tempera and Oil Painting and Woodcut, in which he also participated.

The would-be artist was born on December 2, 1893, in the village if Pidhirky, Stanislav region. World War One cut short his studies at a Kalush high school and thwarted his dreams to enter Lviv University... When the 28-year-old Smolsky came after all to Lviv in 1921, he had an Austrian officers’ course, hostilities on the North-Italian front, and Russian captivity under his belt.

At the time, after the stormy November Action political events, Lviv was under the power of Jozef Pilsudski’s Poland, which had “abolished all the Ukrainian chairs” and banned Ukrainians from applying to the University.

To counter this discriminatory policy, a clandestine Ukrainian University, with Vasyl Shchurat as rector, was founded. Smolsky entered this institution, where he studied at the History Department for five years until the university ceased to exist.

But it is not only history that interested the young adept. Concurrently, Smolsky studied painting at Lviv’s Free Academy of Arts in 1921-22. After meeting the well-known artists Oleksa Novakivsky, he transferred to his studio school. Novakivsky’s school focused on drawing. “The professor takes a charcoal and draws a full-length figure in the right proportions. Everybody follows each move of the professor’s hand, while he steps back in rapture, strikes his cane on the ground, and lectures convincingly: ‘You must draw in such a way that everybody kneels down to you, that all of Europe bows to you. It is not a cheap effect of light and color but nature that should be the source of true values. Don’t complicate things, don’t philosophize, work quietly and modestly,’” Smolsky reminisced.

Looking at young Smolsky’s works of that period, we can trace a certain influence of Novakivsky’s paintbrush in the coloring of the artist’s early pictures, but we can also see the making of an original painting manner, especially in My Father (1925), Boiko from Pidhirky (1928), and In the Early Spring (1932).

After the graduation, Smolsky and his teacher traveled to Italy in 1931 for three months, where they visited Rome, Venice, Florence, and Ravenna and depicted the architecture and views of these cities on small-size canvases.

Aware of the necessity of further professional improvement, Smolsky went to France, into the artistic milieu of Paris, where he studied at the Academie Colarossi in 1934-35.

Back in Lviv, the artist organized a group exhibit at the Natural Museum of the Shevchenko Scientific Society in 1937, where he displayed 40 drawings made in Paris, including Boulevard Montparnasse, A Bridge over the Seine, and Grand Palais.

The advent of the “golden September,” World War Two, and the return of the Soviet totalitarian regime had a negative effect on the oeuvre of one of the brightest Ukrainian artists in the twenty interwar years. Accused, along with Roman Selsky, Oleksa Shatkivsky, Okhrim Kravchenko, and Stefania Gebus-Baranetska, by the communist authorities of “formalism,” “professional backwardness,” and “showing life superficially and in an ideologically disarmed way,” he was admitted to the League of Artists of the Ukrainian SSR as late as in 1958.

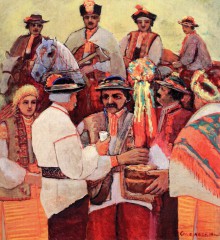

While most artists, who were given access to the “League’s trough,” were busy immortalizing the faces of leaders, merry tractor drivers, athletic steelmakers, optimistic dairymaids with a dozen of well-fed piglets on huge canvases, thus harvesting fabulous laurels and money for their “fabulous heroes,” Smolsky focused on such themes as the life of Hutsuls and views of the Carpathians. The artist rediscovered for himself the Hutsul village of Kosmach, where he had once taken part in Novakivsky school’s plein-air sessions.

Legends about Oleksa Dovbush and his treasures hidden in the nearby mountains and caves, centuries-old customs and rites, the picturesque views of the Carpathians, the bright orange and crimson colors of local folk garments and headgear –A Hutsul Wedding: Dovbush Is Greeted (1956), Princess Bride (1957), Kosmach in the Morning (1960), A Hutsul Old Woman (1962), The Opryshky Rebels in the Mountains (1965), My Kosmach (1967), The River Pistynka in Oblaz (1968), Wedding Matchmakers (1972), and Chrysanthemums (1972) – all this became a parallel to Soviet reality, in which the artist spent the second half of his lifetime.