The artist’s preserved heritage is composed of over 170 easel works, mostly done in egg tempera technique, as well as of about 140 drawings, watercolors, pastels, sketch albums, most of them created in the postwar Lviv. The last 25 years have been the most prolific period of Okhrim Kravchenko’s artistic career – 25 years out of 82! And he could have many more years to his life had it not been the circumstances brought about by the totalitarian system, which is unforgiving to creative individuals.

Kinship is a moral obligation before the father and the people who surrounded him throughout life. In Soviet times, it was considered unethical for a son to write about his artist father (it was not a dynasty of steel smiths or miners!), and thus I had to rely on memory for so many facts of his life... And God gave us a wonderful gift: one of memory, the mirror in which people, acquaintances, episodes “prominently and visibly” appear... Large and small, akin to colored glass shards that make up the stained glass mosaic of memory – invisible to others, but visible for me!

The ambiguous, tragic, and romantic time, in which this man had lived and worked – the 20th century – was the time of the revolution and civil war, famine and collectivization, the World War Two and the movement of national resistance, the lawlessness of Stalin and Brezhnev era until the proclamation of the Ukrainian state, which he had dreamed of and struggled for since his youth, but did not live to see it...

I witnessed the smaller part of his life, but I always was an attentive listener to the terse stories of his own past, and I watched him as he worked... From early childhood I have lived among his works – paintings, drawings, sketches, art albums, and rare “forbidden” books of our library; as well as among his like-minded friends – artists and writers.

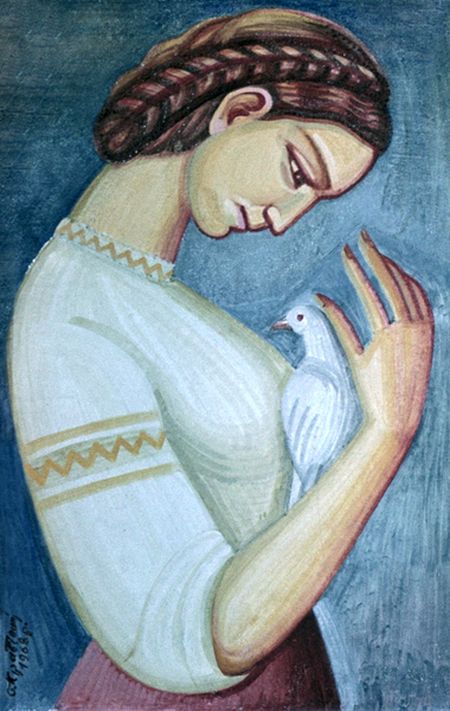

A GIRL WITH A DOVE (1968)

Recalling those years, I feel sorrow – what appalling conditions had this man to live and work in! He created regardless of any troubles – financial or family ones, the rejection of official art scene and the bias of the political system. His entire life was spent in work and respect for the art, which he learned at the workshop of Mykhailo Boichuk; he was not seduced by nor flung away his talent on petty commercial jobs or the “ideological and directed” draughtsmanship at the Union of Artists.

Okhrim Kravchenko was born February 10, 1903 in the village of Kyshchentsi near Kyiv. After the tumultuous events and the collapse of Ukrainian statehood, the boy went to study at Bila Tserkva Art Studio for Young Workers, and then – at Kyiv Art and Industrial College (1921-24), professors Kostiantyn Yeleva and Yukhym Mykhailiv. In autumn 1924 he was accepted to the Painters’ faculty of Kyiv Art Institute. Finding great interest to monumental painting and having some ability for it, Kravchenko and his fellow students Onufrii Biriukov and Kyrylo Hvozdyk were enrolled in the group of Professor Mykhailo Boichuk. Some easel works have survived from those times: Home of My Childhood (1924), At the Beetle (1929), The Old Mill (1930).

Only before the war Kravchenko was allowed to return to Ukraine – to Kryvyi Rih. Being forced to remain in occupation, he worked as an artist for Dzvin journal. He designed Kobza – a collection of poems by Mykhailo Pronchenko, and a novel by Adrian Kashchenko Near Korsun. But when in 1942 the Germans started killing and arresting OUN members, he decides to get to Kyiv on foot; architect Petro Kostyrko helped him to find a job there.

In his artistic beliefs, Kravchenko rejected the “achievements” of The Wanderers and The Socialist Realist, and yet he stood aside of the Lviv school, not always accepting the formal coloristic quests of Roman Selsky and Karl Zvirynsky; firstly, he sought for the “conscious Ukrainian” in Galicians. Fate binds him to like-minded people: Olena Kulchytska, Mykola Fedko, Yaroslava Muzyka (who was another Boichuk’s student, released from exile), Oleksa Shatkivsky, Volodymyr Ostrovsky, and others.

The artist’s workshop at a corner of a two-room apartment on 26, Lysenko Street (a memorial plaque was installed there in 2008, made by Lviv-based sculptor Volodymyr Ropetskyi) was frequently visited by Borys Antonenko-Davydovych, Kuzma Kataienko, Ivan Dziuba, Mykola Kholodny, Les Taniuk, Mykola Svitlychny, Alla Horska, Halyna Sevruk, Liuba Panchenko, and Liudmyla Semykina (the father’s archive has carefully preserved the “anti-Soviet” texts and poems brought in from Kyiv, transcribed by hand and hidden in a closet on the balcony).

At the time of Khrushchev Thaw, Lviv became the center of national creative search, leaving Kyiv and its “grayness of the official socialist realism” behind. Inspired by the process of national revival, Okhrim Kravchenko took his own place in the city’s artistic life, convincingly and consistently bringing to life the principles of Monumentalism on his canvases. In them he saw the expression of national artistic tradition, adopting his teacher’s love to national tradition, to the eternal topics of people’s life, manifested in the “whole and concise shape of a monumental, transcendent image.”

Although the artist was banned from teaching at Lviv State Institute of Applied and Decorative Arts, artists often used to pay him a visit, namely Mykola Krystopchuk, Ivan Ostafiichuk, Vadym Cherkes, Volodymyr Fedko, Lesia Krypiakevych, Stefania Shabatura, Volodymyr Urishchenko, Volodymyr Morhun, Ivan Kryslach, Bohdan Romanets, as “the interest to interpretations of the long neglected ideas of Boichuk’s school has begun to affects the painting of the Seventiers.” He found thankful students in art researchers Bohdan Horyn, Ihor Gereta, Vasyl Hlynchak, Mykola Batih, Oleh Sydor, and Liubov Voloshyna, who recorded their impressions of these conversations in publications on literary and art history.

June 11, 1985 saw the opening of the 4th solo (anniversary, and final – in career and in life) exhibition of Okhrim Kravchenko in the halls of Lviv Union of Artists. As always, he was full of energy, calm and composed, always smiling slightly. And such remained in the memory of the audience and friends... The artist died four months later. “Throughout my life I worked hard and I feel happy,” wrote Okhrim Kravchenko on the last pages of his biography.