The project’s participants have tried to create a collective image of their nation. This resulted in the exhibition “Our National Body” which was on display past year at Arsenal Gallery (which initiated the project) in Bialystok, Poland. It is now brought to Ukraine. In Kyiv it was presented with an endorsement by the Minister of Culture and National Heritage of Poland at the Taras Shevchenko National Museum, a rather unusual place for contemporary art exhibitions. “This is a landmark exhibition. We must talk about our problems and do it in modern language,” says Dmytro Stus, the museum’s director.

A DIFFICULT SEARCH FOR ONE’S SELF

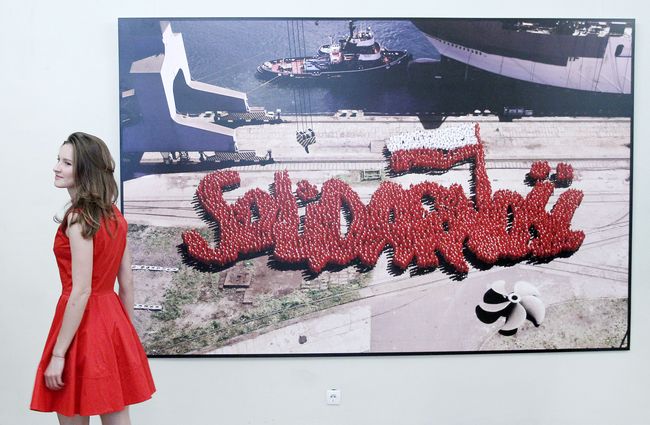

Videos, pictures, documentation of performances, and photos that constitute the display raise sensitive issues, sometimes so tempting to ignore as they are too complicated for a discussion. The mighty crowd, really powerless before manipulation, the ostentatious religiosity, the dogmatic rejection of the other – in Poland, Ukraine, and Russia these topics manifest differently, but they are equally understandable in all three countries.

The “Our National Body” project is valuable not so much in works presented but in the discussions that could be centered on the raised issues. “Working on the exhibition we talked over many things with the artists. In particular, it is important to discuss the things that are painful and hurt us,” says project curator Monika Szewczyk. “I hope that the exhibition will define a new space for conversations and that it will be easy to understand.”

Monika Szewczyk regards the personal experience of the project’s participants as an important factor in speaking about the problems. In this regard, The Murder of Stephen (1), a picture by Aleksandra Czerniawska, Polish artist of Belarusian origin, is remarkable. Through a personal story the author raises the difficult issue of postwar relations between people of different nationalities.

Personal experience imposed on the collective one can be seen in the series of paintings by Ukrainian artist Vlada Ralko. Her “Kyiv Diary” was started during the clashes on Maidan in 2013. It shows personal fears and experience in the reality of the new situation, in which the national body founds itself.

HUMOR AS ANESTHESIA

“When I decided whether to invite Russian artists for the participation, I pondered over the political correctness in this situation of an open military conflict between Ukraine and Russia,” says Szewczyk. “I reassured myself with the notion that these artists have clearly expressed their stance against Putin’s policies, and they can generally be called artists of the world, not only representatives of Russia.” In particular, the exhibition features the documentation of performances by Petr Pavlensky, who counterposes himself against the silent audience. The sewn lips (Seam) or an earlobe cut off (Segregation) – these actions demonstrate the artist’s disagreement with the collective passiveness in regard to the repressive system.

The image of the crowd is explored in the paintings by Polish artist Adam Adach Tribune (1) and Tribune (2). The crowd depicted in the artworks may be a gathering of football fans or it can be a political demonstration. Excitement and sense of power can block critical assessment of what is happening. But the crowd, which seems to be almost infinitely powerful, is often run by single individuals. “I was very interested in how to represent crowds,” says Adam Adach. “It is often used by different political systems, when one group of people is incited against the other.”

An “anesthesia” to help talking about complicated question is humor. In this regard, a series of Marek Raczkowski’s drawings is interesting. In his ironic drawings the Polish artist conveys stereotypical images of Poles. That what seems familiar and normal appears truly absurd. It is revealed in the captions: “Let us pray that during the mourning activities in remembrance of the victims of the disaster, which occurred on the anniversary of the killings, we will not have a tragedy happen” – a notion, familiar to Ukrainians, very funny and sad at the same time.

“Our National Body” is a difficult project. Issues the project explores are sometimes painful even to think of. But the pain is a sign that the body is alive. It signals injury, which must be overcome. Therefore, the national body review is needed – to reveal our injuries and diseases and to choose the correct treatment.

The exhibition will run at the Taras Shevchenko National Museum through June 22.