It is concrete personalities, not the abstract “forces of progress,” that fill and push forward history in general and the cause of human freedom in particular. They are prepared to cross their personal Rubicon for the sake of this freedom, although their friends, relatives, and like-minded persons can so far offer insufficient, modest, if not minimal, support. They are ready to voice a seemingly “hopeless” protest against arbitrary rule, deceit, and outrage against human dignity. Petro Hryhorenko was one of them.

Andrii Hryhorenko, the son of the legendary Ukrainian dissident general, human rights activist, political writer, and public figure, was doing his best to ensure that his great father could feel support from the closest people even in the hardest years of resisting the totalitarian system. In 1964, at only 19, he was arrested by the KGB for membership of a clandestine organization. In December 1965 he took part, together with his father, in a demonstration on Moscow’s Pushkin Square in defense of human rights in the USSR, and then worked as a journalist in samizdat. He was repeatedly detained, beaten up, and dismissed from work for participating in the human rights movement. He always strove to support his father as much as he could, no matter whether Petro Hryhorenko was free or in prison. In 1975, the KGB forced Andrii to emigrate. But he continued his human rights activities in the West, contributed to the major Western media, published a lot of his father’s fundamental works, founded and headed the General Petro Hryhorenko Foundation; was an IT expert, a New York City Hall employee, and ran his own software development company. He has often visited Kyiv and the rest of Ukraine.

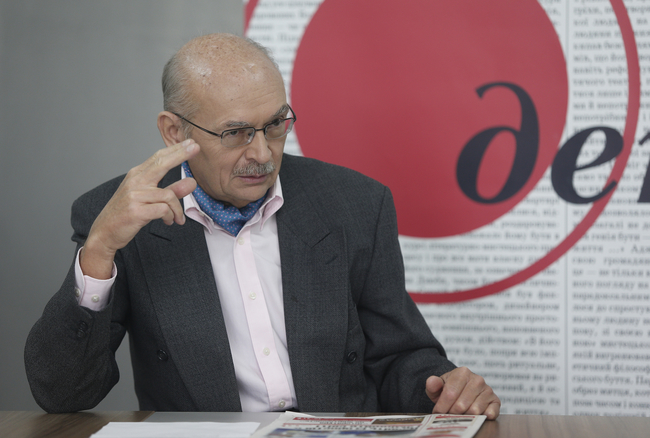

Andrii Hryhorenko visited the Den editorial office on the occasion of the 110th birth anniversary of the unforgettable General (as human rights activists called his father). We thus “devirtualized” the well-known human rights advocate and our contributor, with whom we had only been in touch by telephone and the internet before. We discussed with Den’s guest a number of very topical issues of the current situation in Ukraine and the world – how the Ukrainians can win in the war and overcome enormous difficulties on the way to Europe. The guest naturally recalled what General Hryhorenko was like in the public struggle for freedom and in private everyday life. Andrii remembers many things about his father, who departed this life about 30 years ago in New York, which nobody else in the world may know. Here follows the interview with Andrii Hryhorenko.

“THERE WILL BE NOTHING POSITIVE IN UKRAINE UNLESS A RULE-OF-LAW STATE EMERGES”

Olha KHARCHENKO: “Mr. Hryhorenko, what do you think of the initiative of the well-known dissident Vasyl Ovsiienko who has requested the president to confer the title of Hero of Ukraine on your father?”

“I also know that a request like this was submitted to President Viktor Yushchenko 10 years ago in connection with the centenary of my father’s birth. But this produced no results, and I am not sure now either…”

Larysa IVSHYNA: “What processes in our political sector does this fact reflect? Is our political class aware of the importance of Petro Hryhorenko’s personality and of the trends he embodied? And, in general, what do you think of Ukraine future?”

“I am looking at it from a certain distance. Any society (the Ukrainian one is no exception) has two different vectors of development – good and bad. I cannot foresee which of these vectors will prevail. Let me give you an example. Ukraine has been officially independent for 26 years now, but there are still no accessible Ukrainian language courses for adults. Maybe, it is being done somewhere on a volunteer basis… But it is very important! In New York, if you want to learn English, you just go to any school and sign up for a course – no problem at all. And in Ukraine? The courses in New York are absolutely free of charge. Incidentally, there is no such thing as official language in the US, including New York – each state has its own laws on this. It is just one example. So many necessary things just don’t exist.”

L.I.: “The root cause is the quality of political representation in the country’s leadership. There were a lot of unseized, ‘blown,’ opportunities. We remember the first inspired and romantic Maidan and what happened thereafter. I once said: ‘In 1999 there was a president, but there was no nation; in 2004 there was a nation, but there was no president.’ Nevertheless, there still is a part of the living society that needs a political alternative. Den is working on this. Our newspaper often raises the following questions: why do our revolutions go the other way round? Do we struggle in a right way? And it is worthwhile to turn to the experience of the human rights movement: what can be learned from the past?”

“Obviously, two things: respect for the law and for human rights. I can remember meeting the Russian dissident Yesenin-Volpin, the son of a famous poet (I didn’t know at the time who he was), for the first time in 1962 or 1963, and he said to me: we need the power of the law. No matter how imperfect the law is, it must work instead of remaining an empty slip of paper. It can be improved later, but it is the worst if nobody reckons with the law. I could not understand it at the time, I only grasped it later. And I recalled the words of ancient Romans: ‘The law is harsh, but it is the law.’”

L.I.: “You see? Ancient Romans knew this, but our society still cannot do so.”

“What is needed here is experience. On the one hand, this thing seems to be ‘simple,’ but, in reality, it is very complicated. But there will be nothing positive in Ukraine unless a rule-of-law state emerges. There must be three branches of power: legislative, executive, and judicial – independent of one another. These seemingly banal things should be said over and over again. And the press – it plays a tremendous role. This will create a necessary competition in society.”

“THERE IS CORRUPTION IN THE MAJORITY OF WESTERN COUNTRIES, BUT THIS CORRUPTION IS ABOUT INFLUENCE, NOT ABOUT MONEY”

L.I.: “And this requires independent people, the institution of private property rather than of hostile takeovers, and the independent, rather than oligarch-bought, press. The USSR fell but things didn’t go the way we dreamed of. Why?”

“To paraphrase a Soviet cliche, the ‘vestiges of socialism’ hindered very much (laughter). Let me say about myself. When I was exiled from the USSR, I thought: hurrah, I am free now and can go wherever I want to and do whatever I like. But then I realized: yes, I am in fact as much a Soviet man as all the others. The burden of the past held me firmly by the feet – I was often intolerant and could not accept a different, even inadmissible, view calmly. As Voltaire said, ‘I do not agree with what you say, but I’ll defend to the death your right to say it.’”

Photo by Ruslan KANIUKA, The Day

L.I.: “That’s right, but you will agree that what is now going on in the post-Soviet space and in Europe is really alarming. What is the current president of the Czech Republic compared to Vaclav Havel? What is this – deep-rooted slavery, degradation of even a European society, or really ‘vestiges of socialism’? Or the point is in corruption and the ‘Schroederization’ of Europe?”

“Let me begin from the end – the problem of corruption. This problem exists in any society, and the only question is to what extent it has ‘eaten away’ one country or another. And I know how difficult it is to fight this evil. The point is that there is corruption in the majority of Western countries, but this corruption is about influence, not about money. It is a different thing, i.e., ‘I give you, you give me,’ etc.”

“AS FOR THE PEOPLE WHO PUT MORAL VALUES ABOVE EVERYTHING ELSE, THEY MAKE BAD OFFICIALS”

L.I.: “People should watch these processes, especially in the US, very closely because our society believes too much in that ‘the West will help us,’ and so on. The dissident movement was also once oriented in this way. And now we are watching with alarm the utterly corruptive impact of the Russia Today channel on America as well as other informational attacks.”

“I would not exaggerate the impact of this and other Russian channels on US society. Frankly speaking, Americans show little interest not only in Ukraine and Russia, but also in the outside world in general. They are mostly worried about domestic problems. I remember seeing a collage on the cover of The New Yorker, a left-wing magazine (of a special ‘American’ leftism): a very, very large Manhattan and a tiny terrestrial globe… Of course, any big country has, accordingly, very big problems. If you travel to a tiny state, for example, Lichtenstein, it will seem to you that things are OK and there is no corruption there.”

L.I.: “But let’s get back to the situation in Czech society, which you know very well. Why has it changed so much? What do you think could make it happen?”

“I think the point is that Havel was a marvelous person, but, at the same time, he was a romantic, and it was just a miracle that he became president. And such miracles do not last long. When, for example, Ukrainian human rights activists turn into officials, no miracle happens – everything resumes its course sooner or later. As for the people who put moral values above everything else, they make bad officials. It was and still is the case. To criticize the government if you cannot or don’t want to do anything is a different thing. It is easy.

“I personally have never thought of becoming a top official, although I was invited to go into politics – at the state level. On the other hand, I am interested in international affairs (not offices). Recently, shortly before the 2016 US elections, a Ukrainian delegation with President Poroshenko at the head arrived in New York. It included Mustafa Dzhemilev, a friend and comrade of mine. The president met the presidential candidate Hillary Clinton but refused to see the other candidate – Donald Trump. I told Mustafa that it was a very serious mistake because it was not clear who would win and I had a feeling that Trump would be the winner. And you know what eventually happened. Dzhemilev said then that they had no time to meet Trump. A mistake indeed…”

“FATHER DID NOT EVEN KNOW THE RUSSIAN LANGUAGE BEFORE HE TURNED 13 OR SO”

Ihor SIUNDIUKOV: “Let us discuss (at least briefly) such a broad question as Ukrainian national awareness of Petro Hryhorenko and you, his son. Your father was a Soviet Army general, a department head at the Frunze Academy. On the other hand, he undoubtedly always remembered that he was a Ukrainian. The ‘amplitude’ of his development is impressive: after choosing the path of struggling against the system, after emigrating, he began to propagate worldwide the idea of an independent Ukraine. How did this complicated evolution proceed?”

“As for the ‘amplitude,’ it is not exactly so. Indeed, there was a long and difficult evolution. When still a boy, he enthused about the communist ‘manna from heaven.’ But he saw the Holodomor (he saved my grandfather, his second wife, my aunt from death), repressions, tortures, and the death of so many people. But then the war reconciled him to some extent with the existing system – to some extent because he also saw these crimes against the people during the war. But still… Incidentally, he was the first to write that the USSR was preparing for an attack, not for defense (which was one of the factors that caused defeats in 1941), in the article ‘Hiding the Historical Truth Is a Crime against the People.’

“As far as Ukrainianness is concerned, he naturally knew that he was a Ukrainian from the moment he was born. Father did not even know the Russian language before he turned 13 or so. He could not get rid of the Ukrainian accent until the end of his life. He spoke with me in Ukrainian, and when he had a stroke two years before he died, he forgot Russian altogether and could speak Ukrainian only. My mother not always understood Ukrainian (her vocabulary was insufficient, for Russian was her mother tongue), so I often had to cover rather long distances in New York (I lived separately) in order to ease their communication.”

“RUSSIA STILL REMAINS A COLONIAL STATE”

Ivan KAPSAMUN: “You told our newspaper 10 years ago that General Hryhorenko did not fit in with present-day Russia. There have been hardly any changes in this respect since then. There will be (at least nominal) presidential elections in Russia in March 2018, but Putin has not yet announced that he will be running for office. How long do you think the current state of affairs can last? Are any changes possible?”

“It is impossible to foresee anything, and I will be the last one to try to do so. I am convinced that the main problem of Russian society is that they have not got rid of a colonial mentality. Russia still remains a colonial state, but many people are unaware of this. Tuva was annexed in 1944. Have you ever heard of independent Tuva? Now it is a Russian province. And the Kazan Tatars? It is a country inside Russia, which really has every reason to be an independent state. There are a lot of unresolved ethnic problems in today’s Russia. Although they call themselves a federation, Moscow in fact holds an overall monopoly. The Muscovite state tradition continues to exist now. It was established by Yury Dolgoruky who began to build Asian-style despotism there. All those who succeeded him were despots, including Alexander Nevsky, the key hero of Russian history. When he tried to seize political power in Novgorod, he was ousted from there. Of course, contemporary Russian historiography says nothing about this. Alexander Nevsky was authorized to rule by a Golden Horde khan. The borders of the Soviet-era Russia coincide with those of the Golden Horde. Traditions and even money are also similar. All these historical events have been leaving an imprint on the minds of contemporary Russians.”

L.I.: “Putin recently met the top executives of some influential German companies which had demonstratively agreed to this meeting in spite of the imposed economic sanctions. Therefore, the world is still unaware of the threats that Russia poses.”

“It seems to me that this problem has several dimensions. On the one hand, they don’t want to be aware of these threats. On the other hand, what also matters is money – they can sell their own mother for money.”

L.I.: “This reminds me of the situation on the eve of World War Two. At the time, totalitarianism was the thing that united Germany and the Soviet Union. Today, what unites their successors is love for money. Does what is going on now not resemble the partition of Czechoslovakia?”

“Europe is on the Russian oil and gas ‘needle.’ They are so much dependent that they cannot afford to completely break off relations with Russia. Of course, this in no way justifies them. At the same time, the state of affairs has been changing lately. The US began to actively export liquefied gas and oil a few years ago, which opens up new sources for Europe. Russia is trying, on its part, to set up a new energy infrastructure that will bypass Ukraine. We will hardly like it, but, at the same time, we know why things go precisely this way.”

“THE CRIMEAN TATARS SITUATION IS AWFUL DUE TO THE KREMLIN’S ACTIONS”

Roman GRYVINSKYI: “One more question which we cannot omit in the conversation with you is the current plight of Crimean Tatars. We hear almost every day about new arrests of and repressions against Crimean Tatar and Ukrainian activists in Crimea. Do you think Ukraine and the international community are doing their best to help these people? What kind of moods dominate now among the Crimean Tatars and in the diaspora?”

“The plight of the Crimean Tatars is just awful. It is even difficult for me to imagine how they manage to survive in the occupied Crimea. I recently received a video that shows the way the Russian riot police behave when they detain, search, and brutalize people in general. I am really surprised that a large number of Crimean Tatars have not yet acquired Russia citizenship – accordingly, they cannot stay on the peninsula for more than four months and must move to the territory of continental Ukraine. Most of the Crimean Tatars remain patriots of Ukraine. In its turn, the Ukrainian community in Crimea is divided – one part has surrendered and the other one is faithful to Ukraine. I will also note that there are very many Russian-speaking patriots in Crimea’s Ukrainian community, although there are many people like these all over Ukraine. Incidentally, the Crimean Tatar diaspora in the US is small, but it cooperates with the Ukrainian community.”

L.I.: “We have been repeatedly saying in public that the Nobel Peace Prize should be awarded to Mustafa Dzhemilev. The whole world is watching the destiny of Crimean Tatars today. Even in the Soviet era, when your father spoke in very difficult conditions, this drew certain responses – maybe, because there were Ronald Reagan and other politicians who knew how to heed, whereas today, even though the world is freer and more informatized, it is less sensitive?”

“It is bad to some extent that Crimean Tatars are Muslims because the West is taking a bad attitude to representatives of this religion. It is good that the Crimean Tatars maintain good relations with Turkey, but now, after mass arrests of the opponents of the current political regime, Turkey is somewhat at odds with the West. This is surely not to the Crimean Tatars’ advantage. I don’t like what is now going on in Turkey, but Ukraine maintains not so bad relations with that country because they are your neighbors.”

“I THINK MY FATHER IS A VERY GOOD ROLE MODEL FOR THE NEW GENERATION”

Valentyn TORBA: “There was a heated debate recently between historian Yaroslav Hrytsak and a journalist-turned-politician, Mustafa Nayyem, about the conflict of generations. Hrytsak accused the younger generation of ‘impotence,’ while Nayyem blamed Hrytsak’s generation for having allowed former young communist functionaries to come to power. What is your attitude to the younger generation? How should it be brought up?”

“I think my father is a very good role model for the new generation. He is the example of how to defend one’s dignity in any situation. This was and still is topical. Assessing the young Ukrainian generation at a distance, I can see positive signals. For example, I read the verses of young poets with great pleasure. The simple truth is that many young people go abroad because there are no conditions in Ukraine for them to realize their potential. Comprehensive measures are needed to change the situation.”

L.I.: “Our newspaper has a rubric, ‘Parents’ Day,’ in which everyone can tell about an example from their own life. How was father bringing you up? In general, what helped you mature?”

“Both the family and the street bring up an individual. For example, when I was young, I was rather ‘disobedient.’ I used to fist-fight, carry brass knuckles, a knife, and, later, even a pistol (illegally). This was a street upbringing. All my peers – friends and comrades – served a prison term except for two – myself and another guy. I can’t say they were bad guys – we just lived in such a period and conditions. We resided in a working-class neighborhood on the outskirts of a city.”

L.I.: “Why?”

“Because my parents didn’t want to live downtown. Maybe, it was for the better. What also mattered, I began to work at 15. Incidentally, I hid the fact that my father was a general. There was even this incident. One of my teachers, whose husband was my father’s student, invited him to speak about World War Two in the school. But father did not even have a business suit – he wore a military uniform only. Lack of money, you know. My brother and I presented him with a business suit later. So I said to father: ‘You’d better go to school without me, OK?’ When he came to the school, a girl from my class saw him, ran up to me and said: ‘Andrii, there’s a general down here, he looks like you!’”

“THE WAR HAS KNIT TOGETHER THE UKRAINIAN NATION”

V.T.: “I’d like to give an example. When the 2014 tragedy occurred, there were young guys in Luhansk (not very many, but still a sufficient number), who took rather a passionate attitude to these events, were asking for trouble, and so on. And there were older-generation people, including well-decorated lieutenant-colonels and colonels, who began to do some strange things instead of driving away this scum. This is a gap. There may be some phenomenon in the present generation. Where is it from? For nobody has in fact been bringing it up. Those who are 30 began to study on the basis of Soviet schoolbooks. Where could those who are 20-30 now draw national awareness from?”

“I think it is in the air…”

V.T.: “But you still acquired it somehow.”

“How did I come to understand that Ukraine needs to be independent? I don’t know. I was not born with this idea. At first I did not even see any major difference between Ukrainians and Russians. I did not know the historical difference between the two countries. This came later, when I was reading and searching for something. A funny thing happened somewhere in 1965 or 1966 in the company of some Ukrainian intellectuals. They were talking about the problem of the Ukrainian language, and so on. I was mostly listening, for it was all interesting to me. Then I suddenly saw the point and said: ‘You know, these problems will be resolved only when Ukraine is independent.’ A dead silence. They were wondering if it was a provocation or something else. Later, at midnight, the hostess took Leonid Pliushch outside and said: “Leonid, you’ve brought a gentleman from the center [an interesting point, by the way. – Author], who says in Ukrainian that Ukraine needs to be independent.’ Look, it was in 1965. And we are speaking about the Ukrainian intelligentsia. Maybe, I should not have said it, but we were accustomed to saying whatever we chose at the kitchen in Moscow.

The plight of the Crimean Tatars is just awful. It is even difficult for me to imagine how they manage to survive in the occupied Crimea. I recently received a video that shows the way the Russian riot police behave when they detain, search, and brutalize people in general. I am really surprised that a large number of Crimean Tatars have not yet acquired Russia citizenship – accordingly, they cannot stay on the peninsula for more than four months and must move to the territory of continental Ukraine. Most of the Crimean Tatars remain patriots of Ukraine. In its turn, the Ukrainian community in Crimea is divided – one part has surrendered and the other one is faithful to Ukraine.

“So I don’t know where it comes from. I will say another thing. Whenever I visited Ukraine previously, I saw that it was Russified very much. War is a very bad thing. But, on the other hand, the bad can also bring on something good. The war has knit together the Ukrainian nation. People begin to understand this. It was interesting, when the war began, to hear a man in the street respond in the Russian language to some question: ‘Well, that scum, the Russians.’ Here’s a situation. Where from? From the air.”

“MY FATHER WAS BOTH A ROMANTIC AND A REALIST. BUT HE COULD ALSO HAVE BEEN A POLITICIAN”

I.S.: “At the beginning of our conversation, you characterized Vaclav Havel as a romantic idealist to some extent and said you doubted that people of this kind could make successful politicians. And what about Petro Hryhorenko – could you call him a romantic and an idealist? And could he have been a successful politician?”

“He could have been a politician too. In some cases, people go both ways. Havel was and remained a romantic only, a romantic writer.”

I.S.: “And your father?”

“He was both a romantic and a realist. He knew how to learn and how to listen. It was very difficult in the Soviet era to find a person who could listen. It might seem to be strange that a general, who is to issue orders, knows how to listen – to listen to a soldier. When he was in his first honorary exile, he had a chauffeur-driven car at his disposal. The chauffeur and I were of almost the same age, so we made friends. He used to say: ‘I am very lucky to serve this general – he is not in fact a general.’ He would take meals at his parents’ place, not in the barracks. This is an altogether different attitude. Of course, he was not a ‘normal’ general (smiles).”

R.G.: “At the same time, history knows the examples when the military – the people who formed inside the army corporations – also became political figures and, like your father, public activists.”

“Pilsudski, for example.”

R.G.: “In this connection, the question: in fact a new army is being formed in Ukraine now – not only in terms of arms and logistics, but as what seems to me an influential social and political force. Do you see this? Can a serviceman be a central figure on the political arena?”

“I think he can. On the other hand, the army is a special case. In reality, the oppositionist who emerged from the army is, rather, an abnormal situation, even though my father, my brothers, and some more people were among them. But it is not a normal situation. There must be military dictatorship in the army. But a serviceman can be a political figure.”

L.I.: “In some cases, he even must be one.”

“Yes, in some cases.”