In 2004, newspaper Den published book Wars and Peace, or Ukrainians and Poles: Brothers/Enemies, Neighbors… in Ukrainian and Polish. Then already, before many subsequent events in Ukraine, we highlighted what was truly important in the Ukrainian-Polish relations. “We have to think with future in our minds, so as to understand how many values and interests we have in common, as well as how much we can achieve together,” as the famous Polish Communist-era dissident and journalist Adam Michnik noted in the preface to the Polish edition of the book.

But it turns out that the question of disputed historical issues is still relevant. On coming to power, Poland’s new conservative government, led by the party Law and Justice, started to speak again on the Volhynian tragedy and the purported “genocide,” and it has passed the resolution “On Honoring the Memory of the Victims of the Genocide Committed by the Ukrainian Nationalists against Citizens of the Second Polish Republic,” which has established July 11 as the National Day of Remembrance for the Victims of the Genocide. Den pondered whether it was a case of political speculation and an attempt to stake out the geopolitical interests in the region before, in the article “History or Geopolitics.”

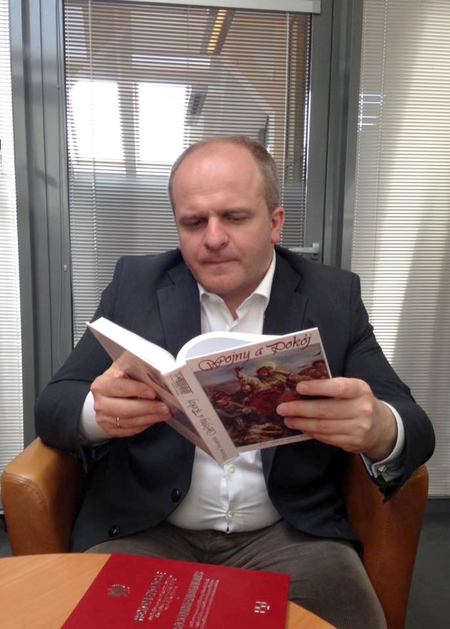

During the conference “Twenty-five Years after the Belavezha Accords: the State, the Nation, the Borders,” The Day asked Pawel Kowal (a Polish politician, historian, journalist, former deputy minister of foreign affairs, Polish MEP of the 7th European Parliament, founder and head of the Museum of the Warsaw Uprising) to tell us his thoughts on whether or not the tragic historical events would impact our future. It was his first interview for the Ukrainian media in a long time. As our talk ended, Kowal received a Polish-language copy of Wars and Peace (part of Den’s Library series) as a gift from us and promised to read it to understand the Ukrainian side’s views of these and other historical events. “Both sides must take steps towards mutual understanding, and this book will help me in that,” he stressed.

Photo from Anastasia RUDENKO’s Facebook page

The Polish-Ukrainian history has already seen official acts of reconciliation and mutual forgiveness. In 2003, Leonid Kuchma and Aleksander Kwasniewski signed the Statement of Reconciliation on the 60th Anniversary of the Tragic Events in Volhynia, and Viktor Yushchenko and Lech Kaczynski continued the same line. Why has the issue of the Volhynian tragedy re-emerged on the political agenda?

“I would not say that this is some kind of incitement of anti-Ukrainian hysteria. In any case, even if the resolution is passed, it will not affect the relations between Poland and Ukraine, which are very important for both countries, and especially now, in the context of Russian attacks. It should be understood that the use of history and inciting history-based strife is a common tool for the far-right in many countries. Such initiators of strife are not always in the majority, but they are able to get their view of history to enter the public opinion, the tone and the discourse. In Poland as well, the question of the Volhynian tragedy is largely used as a political card, enabling people to drum up public support.

“On the other hand, many Polish families were touched by this tragedy, and they do not want the question ignored. We need to do much outside of the political context in order to stitch this wound by finding the graves, identifying the victims, compiling the lists, erecting the crosses, and I mean crosses for all the victims. Of course, it should be a cooperative project between the two governments. Starting with the activities of Pope John Paul II, the Poles and the Ukrainians have done a lot for reconciliation, but in the field of history, we are still just on the level of declarations. At the same time, for example, Poland and Germany have not only made a gesture of reconciliation, but also institutionalized the study of the painful historical issues. Wojciech Smarzowski’s film Volhynia, much reviled by Ukrainians, will soon be released to theaters. But the real question is why have we still not established a Polish-Ukrainian foundation, which would produce feature films about our relationship each year? Why have we built no government-supported institution that would engage in thorough historical research? Activities of such a foundation would cost no more than a district house of culture. There have been many declarations, but no real steps towards the study of the historical truth, and now we are reaping the fruits of this.

“We sent a formal appeal to Polish politicians against passing such a resolution. Speculation on historical issues is evidence of immaturity, for history must be evaluated as it really was. But I doubt that the Polish side will change its approach to the legal characterization of the Volhynian events, because if we call the destruction of even one village a case of genocide, the events with a huge number of people killed cannot be treated otherwise. At the same time, Ukrainian politicians and intellectuals should not take the Polish opinion on the tragedy for an accusation against themselves, as it happens now. These are issues of history, not the present, and we need to perceive these statements in this context.

“In general, it seems to me that an approach stating that people can negotiate, particularly in our part of Europe, the same interpretation of history for everyone – such an approach is somewhat infantile. It is impossible.”

You were a MEP from Poland in 2009-14, how do you think the EU can be reformed after the Brexit, to preserve its viability and efficiency?

“Of course, the threat of the Brexit has badly affected the reputation of the EU. There is no problem of stability, as the stability itself is gone for good. The Brexit has already begun, because the politics as the ‘art of the possible’ begins at the moment when a new path emerges. On the other hand, the Brexit may fail to actually happen, because we are hearing claims that the UK will not send a formal exit notice by the year-end. My forecast is that the UK will delay any action for a very long time, until such time as the new political situation takes shape. Either the EU will agree to continue its relationship with the UK, granting it a similar status to that of Norway, and this can be called, in principle, the Soft Brexit, or the Brexit without the Brexit, meaning preservation of the majority of the real economic links between Britain and the EU, or the UK will change its approach to the Brexit. For example, the coming general election may see an anti-exit party winning. In such a situation, they can say that the election result holds stronger legitimacy than a referendum of the advisory type.

“The main problem of the EU lies in a very weak communication with citizens. The European Commission and European officials lack democratic legitimacy. That is, these institutions want to serve and regulate areas traditionally belonging to nation-states, and it causes rejection. Besides, they do not feel the mood of people, and people do not understand them.”

How can they fix it, and is there an alternative to the EU?

“They should not claim groundlessly increased powers. People now realize that the key element of political identity is the national government, and hence the EU is an important complement, but only a complement. And when EU officials begin to behave as nation-state presidents and prime ministers, their legitimacy evaporates rapidly. But take a look at the history of European continent: there was almost always some kind of European Union, starting with the Charlemagne’s empire. Therefore, there is hardly any alternative to the ‘unity in diversity.’

“The idea of deepening East European cooperation is gaining in popularity. The concept of the Baltic – Black Sea Axis has historical antecedents in the form of concepts of the Intermarium or the ABC (the Adriatic – the Baltic – the Black Sea), these countries face a common danger in the form of Russia, and stronger economic and diplomatic ties are a common interest. It can be a mutually beneficial cooperation.”