Some dates mark well- and little-known holidays. International Thank You Day is celebrated on January 11 in a number of countries as a holiday close and dear to people, families, relatives, friends, as one blessed by the Lord.

Strength implies kindness. This is supposed to be true of physically strong individuals and powerful nations, as is gratitude on a par with forgiveness (although there are things and events in one’s life and in history that are hard if at all possible to forgive). Put together, kindness, gratitude, and forgiveness are a sure sign of moral perfection in an individual and any given nation. Life shows that one must remember everything… crimes, betrayal, bloodshed, but above all good deeds, ones that well- and little-known people in various countries have done for Ukraine.

Why do we Ukrainians, along with historians, diplomats, and journalists, have to remember this? Why is this important for us even more than for people in those countries whose best citizens helped us keep our freedom and national identity, while respecting those of other peoples, centuries or just 30 years back, who are helping us now on our thorny and winding road to liberty and national dignity? Why is it so important for us to preserve the priceless gift of gratitude for and memories of the good services done us?

Gratitude is a virtue found in noble peoples and individuals (and by “noble” I don’t mean blue blood but crystal clear conscience). This gift is also an excellent remedy for the Ukrainian postgenocidal syndrome and accompanying national ills (e.g., ethnic inferiority complex, envy, provincialism, defeatist spinelessness). Den/The Day’s Editor-in-Chief Larysa Ivshyna has repeatedly broached the subject which has been on top of the editorial agenda for the past 20 years.

Our ethnic inferiority complex has been condemned by Taras Shevchenko, Lesia Ukrainka, Ivan Franko, Yevhen Malaniuk, and many other noted Ukrainians. Ukraine has been sincerely respected and praised by a number of outstanding personalities on all continents. This is proof that our country is a full-fledged member of the international community. Envy of another country or people’s “undeserved” success is petty jealousy, spitefulness that defames and humiliates the rival in the first place. When asked whether he was an anti-Semite, Sir Winston Churchill replied that neither he personally, nor the British were ones; they did not consider Jews to be smarter or more talented than they were, so there was nothing to envy them.

We are humiliated by our provincialism – and this despite the fact that a great many noted personalities have felt for Ukraine and regarded it as an important part of European civilization, rather than a backwater province of culture. Add here our (and by “our” I mean both the ruling political class and, unfortunately, a great many ordinary people) readiness to surrender to what is called a “necessary rational even though unpopular compromise.” Surrender and, even worse so, convince others that this compromise is necessary. This is disgusting, considering that so many Ukrainians have selflessly defended this country, its freedom because they hated tyranny and recognized no compromises, even at the risk of their career, well-being, even their life…

Getting to the point, who has done Ukraine good services, when and how? Like I said, I mean people in other countries, among them names little known in Ukraine… I will make it brief because of newspaper format and without strict chronology.

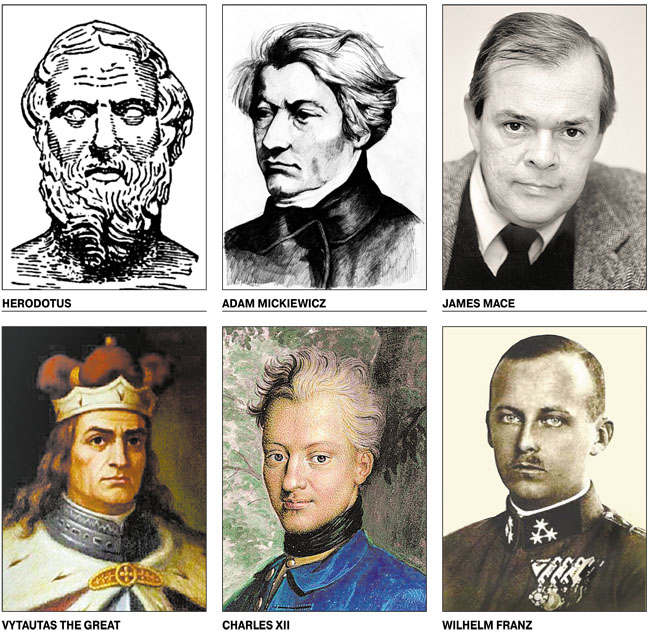

Herodotus, the Father of History, was the first to write in detail about the Scythians and other inhabitants of Europe, including Old Slavic tribes, about their way of life, military campaigns, world views, and political system in The Histories (5th century BC). Even though what he wrote was on the level of ancient Greek science, his legacy remains invaluable in the European cultural treasure-trove.

Adam Mickiewicz, brilliant Polish poet whose poetic dramas Dziady (Forefathers’ Eve), Konrad Wallenrod, and Pan Tadeusz remain an unforgettable hymn to liberty, a prophesy of the inevitable inglorious fall of the despotic monstrous Romanov empire, of the eventual liberation of all Slavic peoples, particularly the Ukrainian nation. Mickiewicz knew and respected Ukrainian culture, as evidenced by his lectures on Slavic literatures in Paris in the 1840s. Taras Shevchenko knew and praised his poetry. His friend Oleksii Savych met the great Pole on the banks of the Seine in 1847 and, according to all historical sources, told him about the Ukrainian poet. Mickiewicz’s name was strict taboo in Russia under Nicholas I and his famous line about a chained dog who bites the hand that tries to pull apart his chain (addressing his former Russian intellectual friends, primarily Alexander Pushkin who had sided with the empire and its chauvinism) remains topical.

We will always remember Dr. James Mace, native American, historian, public activist, a brilliant contributor to The Day. It will soon be 12 years since his passing, but the feeling is as though he has just walked out of the office, softly closing the door, having done so much for Ukraine and the international community with his systemic and ruthlessly truthful analysis of the Holodomor in 1932-33, revealing the causes and consequences, coming up with the postgenocidal concept. This gifted political scientist with encyclopedic knowledge and striking foresight sacrificed a spectacular academic career in the United States and dedicated the rest of his life to Ukraine. His heart beat its last at the age of 52.

We will always feel grateful to the honest British journalists Gareth Jones, Malcolm Muggeridge, and Lancelot Lawton who wrote the truth about the Great Famine of 1932-33, noting its organized systemic nature (compared to the pro-Kremlin “progressive public stand” taken in the West by Bernard Shaw, Edouard Herriot, Walter Duranty, et al.). Lawton spoke in the House of Commons in 1935, saying that “it would be hypocrisy to deny that an independent Ukraine is as essential to this country as to the tranquility of the world.”

Vytautas the Great, ruler of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania which then incorporated most our current lands. His was an interesting and powerful regime, the strongest in Eastern Europe in the 14th-15th cc., with Ukrainians and Belarusians making up a considerable part of the ruling class. The duchy was actually a political union of the Lithuanian, Ukrainian, and Belarusian peoples that dominated that part of the Old World – and Muscovy feared it! After the death of Vytautas in 1430 the duchy began to lose power, falling under the influence of the Polish kingdom (Rzeczpospolita), but Ukrainians must remember it as a powerful state and that their ancestors were among its founders.

Charles XII of Sweden. Although defeated by Peter I in the Battle of Poltava, his statement that the Swedish army sought to free Ukraine from Muscovite tyranny sounds truthful enough, considering that the king was a straightforward warrior and fought under enemy fire. He also deserves our gratitude. Ditto Ahmed III of the Ottoman Empire who flatly refused to deport Hetman Ivan Mazepa to Muscovy although Peter I promised him mounds of gold, diamonds, and swords and guns adorned with precious stones in return.

Archduke Wilhelm Franz of Austria (later Wilhelm Franz von Habsburg-Lothringen; also known as Vasyl Vyshyvanyi) who gave his life for the freedom of Ukraine; Alexander Herzen, one of few spiritually free Russians who called for unchaining the hands of Ukrainians; Tomas Masaryk, the first president of democratic Czechoslovakia who set up a unique network of educational establishments for the Ukrainian patriots in exile (that would eventually produce intrepid OUN warriors and cultural figures); last but not least, Pope Saint John Paul II (Karol Wojtyla), son of a Ukrainian mother, with his immortal call on the Poles, then Ukrainians and all other peoples: “Do not be afraid!”

Mentioned above only few of many names. Each rates a separate story and The Day will write them.