Markian Kamysh from Kyiv is a writer and illegal explorer of the Exclusion Zone. His debut novel Oformliandia, abo prohulianka v Zonu (Oformliandia, or a Trip to the Zone) was warmly welcomed by critics and praised as the most interesting debut of 2015. This spring Oformliandia will be printed in France in one of Europe’s most renowned publishing houses, Arthaud (Flammarion Publishing Group).

The novel is based on the author’s real-life experience: over the past 5 years he has made more than 60 trips beyond the barbed wire fence. The second Chornobyl-themed novel by Kamysh will be published in April.

How did you actually become interested in the Zone?

“My father is a liquidator [Chornobyl disaster relief worker. – Ed.]. He worked at the Institute for Nuclear Research, and after the disaster most of the staff went to work at the Chornobyl Nuclear Power Plant. I was born a couple of years later. So for me it is a background theme. Sometime around 2009 I realized that the Zone was a unique place, one of a kind, and also that Ukrainians did not write about the current state of things there at all. Last year my Oformliandia was brought out. This is real experience literature, with a Hunter Thompson style protagonist roaming around the Zone.”

CLEAN-UP WORKERS IN FACT SAVED KYIV AND UKRAINE

What was your first impression?

“I and another newbie had an experienced guide. After 55 kilometers of hiking my feet were sore, I could barely trudge along. In the summer Prypiat resembles the jungle, but it was a starry night in November, freezing cold, bare trees, and the town seemed endless. Moreover, ‘metallists’ (hunters for scrap metal) were at work. Just imagine the picture: we are walking along a deserted avenue by night, and nearly each house is echoing, as if a smith were smashing his hammer against an anvil, and we realize that it would be best for us not to cross paths with those guys. Those fears, the icy wind, and the realization that you are actually in a city where no one lives, they left you gobsmacked.”

How did your expectations of the city change?

“I did not expect to see such wilderness there. Second, I realized that deserted places inspire peace of mind and solace, rather than sadness. This is a nook for a dreamer and misanthrope where no one will disturb me, where I can freely roam the streets without worrying over things. The lack of adrenaline was in part the reason why the scene of my next Zone-themed book is set in Kyiv: it is an attempt to let the reader and myself feel the deserted, unknown City again.”

CHILDREN SUFFERED THE MOST FROM THE ACCIDENT

By the way, why are all your trips to the Zone illegal?

“You have to spend a couple of days there in order to feel the city. It is very important that you sleep there, wake up, walk out to the balcony with a cup of coffee in your hand, like a true city dweller. You cannot get this on a legal excursion.”

What myths about Prypiat are out there?

“The biggest one is that it is dead. Actually, it is not. There is an industrial laundry, a water fluoridation station with stray dogs that are occasionally fed by people. The city is rather half alive.

“The second myth is the big silence. It is not quiet there. You hear all sorts of noises: someone drove a load of scrap across the central square; a group of tourists passed (Japanese at that); at the station, a dog is barking; a saw whines in the distance. And you lie sleepless on a sheet of Ruberoid thinking: ‘I’ve come such a long way, why won’t shut up at last!’ And only at night the city does die, after the curfew. In this respect the best place to be is the army quarters named Chornobyl 2, situated near the well-known radar from the The Russian Woodpecker, a film. This is where you can find perfect silence. There is no one to fear there, and no one will hunt you down.

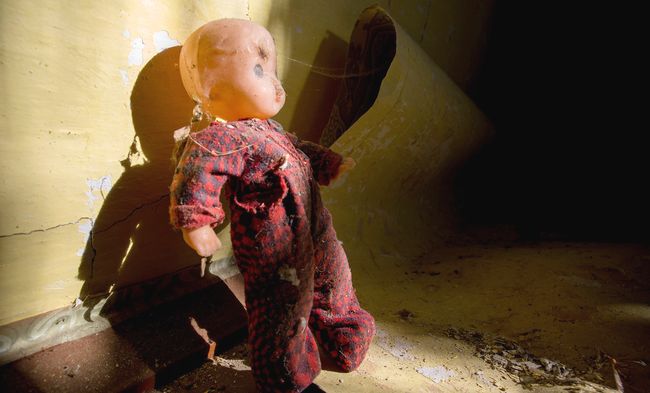

ABANDONED TOYS ARE ONE OF THE MOST STRIKING SYMBOLS OF THE CHORNOBYL NUCLEAR POWER PLANT DISASTER

“The third myth is that the city is intact, with personal belongings still in their original places. In fact, marauders even dig out pipes on the streets. In some apartment blocks, metal railings are sawed off for scrap. A realistic illustration of transience.”

What are your favorite places?

“The outskirts. The greenhouses, for instance. A huge greenhouse with caved-in roof and gaping holes in the walls. On a sunny day you can feel the weight of the city air there. Another one is a market in the southern part of Prypiat. No one comes there, there is nothing peculiar about it. But you develop a taste for unpeculiar places. I also like District Two a lot. The wild growth is at its wildest there, and a lot of artifacts have survived: a Soviet Press kiosk, a fruiterer’s ‘cage’ for watermelons, a bathtub discarded by marauders, a merry-go-round on a playground all carpeted with moss. And the roofs, of course. The most popular ones are two 16-storied buildings in the central square. Cool, but trite. I like another high-rise building which stands aloof on Lesi Ukrainky St. It offers a great panorama of all the nine- and five-storied apartment blocks, with their overgrown roofs and puddles on them. Another popular lookout point is on top of a 16-storied building on Heroiv Stalingradu St. On a sunny day in November, when the trees are almost bare, just tilt your head slightly to the right, and you feel like a bird, as if you are in another world.”

What do you think is the symbol of the city?

“There are a couple of them. Last summer my friend, a photographer, shot a room with a tiny tree growing precisely in the middle of the open window. A striking image of overwhelming nature. The city’s profile changed for good when they started building a new shelter, one of the world’s largest arch constructions. When I see it, it feels like distant future, where this concrete belly rises above the forest like the history museum from H.G. Wells’s Time Machine. The city must have an archetypal symbol. Not a deserted giant wheel, but this combination of gray and green, epitomizing the victory of nature over man. There is another image from this group which I photographed once: a white, typically Soviet-time wall with a vine climbing up from the ground to the ninth floor. Such an outburst of life, Amazonia. A weird, scary, endless sea of life.”

What kind of people do you come across there?

“The most typical ones are the personnel at the station and laundry. They live like inconspicuous earthlings, work to get their bonuses, wear cheap camouflage, speak a central Ukrainian vernacular with a lot of swear-words, they are warm-hearted and they like to drink. Just your ordinary blokes.

“Metallists are a much more interesting sort. Guys with monochrome inks, iron teeth, five-millimeter crew cuts, and the manners and slang to match. They sit in a wooden hut at the station Yanov, grilling poached boar and smoking pot. Interestingly, they saw metal for scrap almost officially. They are not those wretched losers with old, rusty bikes, who would walk 50 kilometers to nick some copper cable. The metallists are working in coordinated groups, and they have the tools. When they come across illegals, they can: a) have a drink with them; b) thrash them; c) invite them to their quarters and hand them over to the cops. Three days before the end of the reporting period, a third category comes into the picture: a couple of conventional cops. They are your typical pigs, but there is a shade of difference: they are kinder than their counterparts on the mainland. When they catch kids with cameras, they don’t punish them.

GRAVEYARD OF EQUIPMENT

“The illegals, too, fall under several types. I have labeled the first ‘camouflaged Pokemon.’ They sport expensive boots and camo, they have all sorts of gadgets and look so serious as special agents on a mission. Also, there are picnickers. They are casually dressed and they can set on a trip to the Zone on the spur of the moment. Then, there are typical hobos wearing old gym shoes, with gallons of booze, they look like battered US troops in Indochina. And there are also game junkies, a lot of youngsters, recently. I would like to mention one of the illegals separately. He is constantly wiretapping the air traffic controllers’ frequency. There is an air corridor just above the Zone, and from time to time you can hear a distant whirr of a plane. And if a plane is passing over, and this guy is listening in to the dispatchers’ talking, it gives an unworldly feeling.”

And where do you belong?

“I belong with the hobos. I go there and do weird stuff.”

Popularization of the Zone: is it good or not?

“In Europe the demand is enormous, but we do not have the proposal. I think this is the reason for Oformliandia’s success. It is unlikely that Flammarion should buy lousy texts, but they are also interested in our wild, authentic stuff, they look for something different.”

What do you think of the idea of turning Prypiat into a museum?

“Of course, a couple of places deserve the status of preserve. However, this would require a change in legislation. To start with, it would be just cool if someone would simply renovate at least one entrance hall or cleaned up one backyard. You walk the deserted city and suddenly find yourself cut to the quick: oh, this is what it looked like back then! Such leaping in time would be stupendous. Although it would be hard to implement, given the numbers of vandals.”

How do you see the future of the Zone?

“I like to dream that 3D printing technology will allow us someday to print the whole city anew, and restore a theme park. One neighborhood as it was in 1986, another in 1990, the third dating back to 2000, the fourth to 2015. People could travel in time just walking among them. Dream on, dream on… At the moment, virtual reconstruction seems more feasible. It will be soon completed, and it will indeed offer an opportunity to take a walk through the city as it was in 1986. I hope that in the next decade Ukrainians will wake up to the Zone theme. This city has a future. It is in our minds.”

I think it is needless to ask if Prypiat has its own mystique.

“When I started writing about it all, it was with a pinch of magic realism. I take Prypiat like a living being, but I never resent it. I give names to buildings, and I talk to them. The buildings have names, the vines look like ink on their skin, the greenery can be anything from emeralds to flying chartreuse-colored jellyfish, the bridge over the Prypiat River – a dragon, dumped by the firefighters into the water and extinguished there, and now trains run along its spine to the station.”

Is it right to say that Prypiat has shaped you as a writer?

“It is not the Prypiat, it is the Zone. No one ever goes to the villages along the border, while they offer a bonanza of material. I discovered those little farmsteads, there were even no photos of them available, I took my friends to see them. So Prypiat is not number one. I went there to capture the material, but eventually the material captured me.”

And last, but not least: which metaphor is most fitting this city’s image?

“A bee stripe on a hot summer’s day. The moment when the world was put on Pause.”