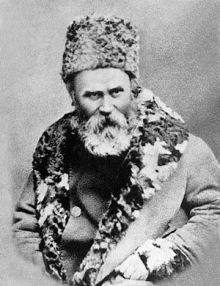

Ukrainophobia is spreading its wings ever more brazenly over our land (this sarcastic irony of history is by no means an invincible divine scourge: it is a natural result of our complacency, indifference and blindness) and assuming a form of “Shevchenkophobia.” Yet this malady has existed for as many years as Ukrainians and non-Ukrainians have known the name of Shevchenko. And it is not the arduous lampooner and “Shevchenko researcher” Buzyna who appears as a trail-blazer here — incomparably more prodigious figures used to work in this field: from the great critic Vissarion Belinsky and pre-Revolutionary high-ranking hierarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church to the present-day “knights” of the Russian world. Shevchenko was and still is equally hated by all.

And it is clear why. For in the poetic genius is a humanized and generalized symbol of Ukraine, our historical road, national character, and the Ukrainian soul. Moreover, if read and understood, he is the guarantor of our statehood and national identity — a true guarantee of Ukraine’s grandeur. The formal, empty and ritualistic “tributes,” which high-ranking bureaucrats forcibly pay on every March 9 to Shevchenko, are in no way such a guarantee.

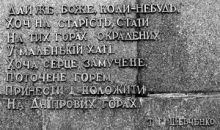

So, even one and a half century after his death, Shevchenko does not leave people indifferent, for he is the ultimate justification of Ukraine’s existence in this sinful earthly world (to be more exact, it is not he personally but the awareness of the sense of his life and his ideas). And in no way are the disputes over his personality and legacy abstract or scholastic discussions because the question is not only about the honor of Shevchenko but also about each of us. And to pave the way to the truth, one must go to Shevchenko and become aware of his time, his pain, his dreams, his love, and his hatred. Otherwise we will be dealing not with a true genius, with all his ups and downs, but with a fictional idol and will provide grounds for the cunning and pharisaical calls of Ukrainophobes: “Don’t make an icon out of Shevchenko!” The best way to know the true Shevchenko and begin a dialog with him is — in addition to studying his poetic and prosaic legacy (including Diary) — to attentively read his correspondence. Shevchenko’s epistolary oeuvre is not only a valuable source for his life stories but also a unique opportunity to feel how sincere and open (“non-cunning,” to quote Shevchenko) this person was, how boundless the space of his spiritual interests was, and how strong his will and love for Ukraine was (“My poor Fatherland”; let this phrase not seem sentimental to the reader, for it really hides a volcanic wrath). These letters, which the author wrote in the cold “mire” of Petersburg and in the hot sands of the Novopetrovsk fortress, in his native Ukraine and far away in a strange land, show a true Shevchenko — neither an “icon” nor one falsified and vilified by Ukrainophobes. He does not need to be defended: if you come to know him the right way, you will see that he still can save Ukraine more than once. It is regrettable that, compared to Kobzar, the poet’s epistolary legacy still remains relatively unknown, on account of censorship. So let us read some fragments of the genius’s most interesting letters.

1. From a letter to Bronislav ZALESKY, February 10, 1857, Novopetrovsk fortress:

“For the souls of those who sympathize and love, castles in the air are stronger and more beautiful than the material palaces of an egoist. Positive people are not aware of this psychological truth. These positive people are pathetic. They are unaware of the most perfect and supreme happiness. Slaves deprived of freedom – and nothing else.”

2. From a letter to Varfolomiy SHEVCHENKO, a relative, November 2, 1859, Petersburg:

“One more thing: if Kharytia (the girl Shevchenko sought in marriage. – Author) says she is poor, an orphan, a hireling, while I am rich and proud, tell her that I don’t have many things, sometimes even a clean shirt. And I borrowed pride and cheek from my mother, a country woman, a hapless serf.”

3. Letter to Varfolomiy SHEVCHENKO, December 7, 1859, Petersburg:

“Now about Kharytia. Your advice is good. Thank you. But you just forgot one thing, and you know only too well that I am, in flesh and in spirit, the son and brother of our unlucky people, so how can I possibly associate myself with landlords’ canine blood? And what will this educated young lady do in my peasant-style house (which Shevchenko dreamed to build but never did so in his lifetime. – Author)? She will die of boredom and cut short my not-so-long age. That’s what it is, my brother, my only friend.” (I wonder how these words can correlate with the myth about “Shevchenko the dandy” which, for some reason, is spread by some “modern” journalists and writers. – Author.)

4. Letter to Bronislav ZALESKY, November 8, 1856, Novopetrovsk fortress:

“I recently hit upon the idea of dramatizing the evangelical parable of the prodigal son, the mores and customs of the present-day Russian society. The idea is in itself very instructive, but what heartrending pictures I conjured up about this genuinely moral topic! Pictures with the minutest details are ready (in my imagination, of course), and, if I had even the most meager means, I would finish the work. I am almost happy that I have no means now to begin it. The thought has not yet ripened, and I could easily make blunders. And as the winter goes by, I will surely reconsider, cherish, and bear, like a mother bears a baby in her womb, this infinitely diverse subject, and in the spring I will pray to God and begin to do it even in a dog’s kennel.”

5. Letter to Mikhail SHCHEPKIN, February 10, 1858, Nizhniy Novgorod:

“My dearest friend,

“Is it a liar magpie that brought you the news that I do nothing but make merry here? It’s a lie. For God’s sake, a lie! And just think a little by yourself. Who on earth will honor us if we do not honor ourselves? I am no longer a silly boy. Nor have I so far turned, thank God, into an old fool to do what you are writing about. You, my lovely dove, just spit at these stupid lies and know: even slavery and sorrow could not overpower me, so I will never fall down.”

6. Letter to Varvara REPNINA, February 15-29, 1848, Orsk fortress:

“I could not finish the letter yesterday because my comrades, soldiers, had just done an exercise and begun to tell me who was beaten and who was supposed to be beaten. There was so much noise, din, and balalaika. They turned me out of the barracks, and I went to see an officer at his billet (thank them, they all receive me as a comrade), and no sooner had I begun to finish the letter… Can you imagine my anguish? It was worse than in the barracks, these people (God forgive them) area laying claim to being educated and well-mannered because some of them were sent form Western Russia. Good Lord, am I also destined to be like them? Terrible! Please write to me and send books.”

February 27: “The most quiet and suitable time now is the eleventh hour at night. Everybody is asleep, the barracks are illuminated with one candle, near which only I am sitting and finishing my haphazard letter — a Rembrandtesque picture, isn’t it? But even the greatest genius of poetry will find no consolation for humankind in it.”

February 28: “Let us beat the blues with a hope and a prayer. Strange! I used to look on animate and inanimate nature as the most perfect picture, but now my eyes seem to have changed: no lines, no colors – I can see nothing. Have I really lost this feeling of beauty for good? But I valued it so much! I cherished it so much! Yes, I must have committed a deadly sin against God if I am being punished so terribly.”

7. To Andrii LIZOHUB, December 11, 1847, Orsk fortress:

“I asked Varvara Nikolaievna to send me some books, and now I am also asking you because I can see not a single letter here than those in the Bible. If you find in Odesa a Shakespeare in Ketcher’s translation or Odyssey translated by Zhukovsky, please send for the sake of the one who was crucified for us, for, by God, I will go crazy out of boredom (Shevchenko insisted later that a book of Lermontov’s works also be sent. – Author). I would mail you money for this all, but I’ve lost it to the last penny somewhere.”

8. To Pavel HESSE, the civil governor of Chernihiv and, later, Kyiv; October 1, 1844, Petersburg:

“The history of Southern Russia amazes one with its events and semi-legendary heroes, the people are surprisingly original, and the land is beautiful. And all this has not yet been put before the eyes of the educated world, although Little Russia has long had composers, painters and poets of its own. I do not know what carried them away and made them forget their own things. It seems to me that even if my homeland were the poorest and most negligible on Earth, it would still look better than Switzerland and all the Italies. Those who have seen our country even once say they would like to go on living and die on her most beautiful fields. What can we, her children, say? We must love and be proud of our most beautiful mother. As a member of her great family, I am serving her if not for essential benefit then at least in the glory of Ukraine’s name.”

9. To Andrii LIZOHUB, October 22, 1847, Orsk fortress:

“My dear friend,

“The next day after I left you I was arrested in Kyiv and put into a Petersburg dungeon on the tenth day. Three months later I found myself at the Orsk fortress with a gray soldier’s coat on. Surprising, isn’t it? But this is the case. So I am now exactly like that soldier whom Kuzma Trokhymovych (a character in Kvitka-Osnovianenko’s short story Soldier’s Portrait. – Author) described to a gentlemen who reveled in vegetable gardens. Just look at the Kobzar! He grabbed the money and snuck beyond the Urals to have a jolly good time with the Kyrgyz. I am having a ball! I wish nobody would carouse like this, but what can I do? I am now strictly forbidden to draw and write anything but letters. It’s as boring as they come. There is not even a single book to read. I wander over the Ural and… no, I don’t cry, something much worse is happening to me.”

10. To Varvara REPNINA, October 24, 1847, Orsk fortress:

“I am now vegetating in the Kyrgyz steppe, at the poor Orsk fortress. I would surely burst into laughter if you saw me now. Just imagine the clumsiest garrison soldier — unshaven, with tousled hair and a monstrous mustache — it is me. A funny thing, but tears are trickling down. Nothing to be done — it is God’s will. What is more, I am most strictly forbidden to write and draw anything, while there are so many new things here. The Kyrgyz are so picturesque, original and naive that my hand is just reaching for a pencil, and I get stupefied when I look at them. The local landscape is oppressive and monotonous: the meager rivers Ural and Or, the barren gray mountains, and a boundless Kyrgyz steppe. Sometimes the steppe livens up with Bukhara-bound camel caravans which loom far away like sea waves and eventually double my anguish. But I still consider myself happy in comparison with Kulish and Kostomarov: the former has a beautiful young wife, and the latter has a poor, kindhearted, old mother, but they are suffering the same fate as I am” (it is interesting to compare this with the classic poem “To Kostomarov” in The Kobzar. – Author):

…My brother,

I can see your mother./

She is blacker than

the black soil,/

Walking as if she has been taken off the cross…/

I am praying to you,

my God!/

I will never stop

praising Thee!/

I will share my prison

and my fetters with none!

11. To Andrii LIZOHUB, March 7, 1848, Orsk fortress:

“Let us not be sad, let us pray. The woe is still far away, and, as wise people say, any woe looks more terrible at a distance.”

12. To Osyp BODIANSKY, May 1, 1854, Novopetrovsk fortress:

“You see, I hit upon an idea long ago to translate The Tale of Ihor’s Campaign into our dear, our beloved, Ukrainian language. Please get one and pass it to the fellow who will come to see you – he will then send it to me. Thank you, my gracious friend, for the (Cossack-era. – Author) chronicles. I have received them all, and now I read them little by little. Do you have by chance at least a trashy copy of Velychko’s chronicle? If you have one, give it to that fellow, and he will send it to me, and I will pray to God for your health.”

13. To Bronislav ZALESKY, October 9, 1854, Novopetrovsk fortress:

“In all respects, a human needs a human.”

Why have Ukraine and its people extolled so high the figure, oeuvres, and the very spirit of Shevchenko? Why did he — who, as we can see from his letters, was not an icon at all — become the prophet and symbol of our nation? Because he possessed a God-given talent? This is a right, but incomplete, answer. The point is that this God-given talent revolved, as the Earth does around the Sun, under the influence of one cosmic passion — love, a love for Ukraine. It was a real, not mythical, love, although there once emerged a big opus, Shevchenko as a Mythmaker. Moreover, the “myths” that Shevchenko saw in his Fatherland have more than once materialized. It is a love for people, especially for “little ones,” no matter what nation they belong to. It was a merciless love worthy of biblical prophets: he more than once hurled the bitter truth into the face of his own people without humiliating them and himself with flattery. But this love was the same as the one that once created the world and Ukraine. Therefore, it will never die.