This is a joint Ukrainian-Italian project under the patronage of the Italian embassy, assisted by the Italian Institute of Culture. There will be three Italian guest stars: the famous bass, Ricardo Zanellato (as Zaccaria, high priest of the Jews), and two talented singers from the Luciano Pavarotti Foundation: tenor Allesandro D’Acrissa (as Abdallo, Babylonian soldier) and mezzo-soprano Elisa Maffi (as Anna, Zaccaria’s sister). The Ukrainian prima donna, Liudmyla Monastyrska, will sing as Abigaille, supposedly Nabucco’s elder daughter.

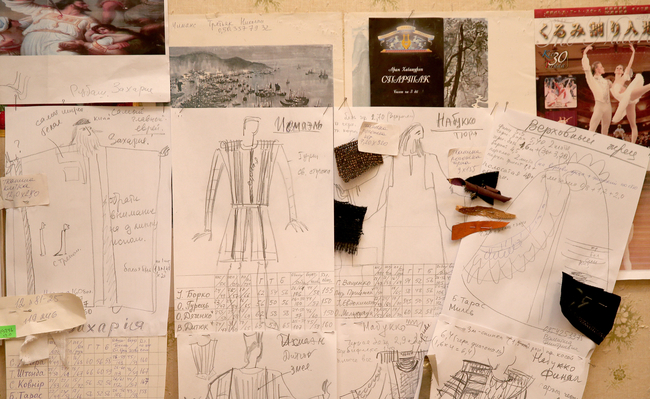

Stage director: Anatolii Solovianenko; conductor: Mykola Diadiura; choirmaster: Bohdan Plish; production designer: Maria Levytska. Everybody is working hard, considering that over 300 costumes have to be sewn and stage props built. What The Day’s photojournalist and I saw was awe-inspiring: huge stage props and fantastic costumes, each a true work of art.

Maria Levytska is a stage artist by the grace of God. She is talented and very creative. Among other things, she learned Italian to study that country’s creative legacy without an interpreter. She is a third-generation Kyivite. Her mother Iryna Levytska was a noted monumentalist architect, her father a physics researcher, her grandmother was a film star in the 1930s. She comes from a family of intellectuals where art was held in esteem and several languages used on a daily basis.

THE NATIONAL OPERA’S SEWING WORKSHOP EMPLOYS 22 PERSONS

Maria Levytska is a pupil of the legendary artist, Danylo Lider, and her diploma project was the stage design of Pedro Calderon’s El Principe Constante at the Youth Theater (sketches are still at her studio), although the project proved a scandalous failure, with the manager of the drama company and the chief stage director losing their jobs and the play being deleted from the repertory. It was a hard blow to the young artist, but Maria did not give way to despair. She worked as a costume designer at the Dovzhenko Film Studios (e.g., The Return of Butterfly about Solomia Krushelnytska). She says she fell in love with production design largely owing to Iryna Mostova. While working as a costume designer at the Dovzhenko Studio, she made costumes for three Kyiv Opera productions. The administration liked them so much, the young artist was offered the post of chief production designer of the National Opera of Ukraine in 1989. She has been there ever since.

We arranged for a meeting with Maria Levytska by the monument to Mykola Lysenko. She invited us to visit the National Opera and we fist went to the sewing workshop. The visage of each production is born of the joint effort of a team, she told us. The costumes were strikingly beautiful, playing with colors, fabrics, needlework. She climbed a stool to demonstrate the velour and applique cloak of the High Priest of Bel and didn’t wince even when the fabric was actually pinned on top of her dress because the cloak wasn’t finished (masterfully fitted by Tetiana Shapovalova who also sews all the male and female opera and ballet costumes).

“IT HAPPENS THAT YOU CONCEIVE AN IDEA, BUT THEN ANOTHER ONE COMES WHILE WORKING ON THE FIRST ONE. THIS IS GREAT, BECAUSE THIS MAKES THE FINAL PRODUCTION BETTER,” SAYS THE ARTIST

After that we went to Levytska’s studio where the walls displayed pictures and sketches of various production designs, with a model of the Temple of Solomon in Jerusalem from Nabucco’s Act 1 in a corner.

HIGH ART AND TELEVISION

Levytska: “My 27 years at the company say that a good production always plays to a full house. The National Opera keeps a high style and our repertoire includes world and Ukrainian opera and ballet masterpieces. This is Ukraine’s number-one stage, so we must keep our standard high, and we do. People develop a fancy for ballet and opera at various periods in life. Much depends on the family. If the parents start taking the child to the Opera at an early age, I’m sure this child may eventually become a true admirer of this art. But these are the times of pop music.

MARIA HERSELF DEMONSTRATED A VELOUR CLOAK STREWN WITH APPLICATIONS SHAPED AS A SPREAD WING, WHICH PERSONIFIES THE HIGH PRIEST OF BEL

There is no use trying to compete with it. Ours are different audiences. Some prefer to watch TVs where some of the programs are good, especially on the Culture and Mezzo channels. I watch Italian channels on the Internet, there are interesting broadcasts about artists, recorded concerts and plays. Several days ago I watched a great one about Medici, about how the famous Renaissance architect, Filippo Brunelleschi, designed the Cupola of Santa Maria del Fiore. I couldn’t tear my eyes off the screen. Too bad there are no such broadcasts in Ukraine.”

HOW IDEAS ARE BORN

“More often than not I conceive my creative ideas in the kitchen, while cooking, or down in the Metro. Sometimes an idea comes in a dream. Also, I may get an idea running down the National Opera’s corridor. I suddenly see the colors I’ll use in the next production. I read a lot and browse the Internet, gathering all finds in my own small treasure-trove when thinking over a production. It’s then I have various ideas. Sometimes I make sketches, other times I can see the whole picture even before I draw it. I work a lot. I use every opportunity to visit the country where the opera or ballet is set. I visited Burgos, the former capital of Castile, before the opera Don Carlos was staged. It was a ten-hour bus ride and then I had to walk through the woods to reach the medieval cathedral. The cashier at the entrance was amazed to see me with a backpack, without a car, and finally said I didn’t have to pay. He must’ve watched me eyeing the El Camino de Santiago the way a devout adherent would. He even allowed me to take pictures of the interior. Those pictures later came in very handy. It happens that you conceive an idea, but then another one comes while working on the first one. This is great, because this makes the final production better.

WORK IN FULL SWING WITH OVER 300 COSTUMES TO BE MADE ON TIME

ON COMPROMISE

“The theater is where compromises are achieved. The production designer, however gifted, strongly depends on the stage director. The two must come to terms. I have never quit a production except once, after the premiere of a ballet, after the ballet master (I will not identify him) had made several strong-worded statements, I suggested that my name be deleted from the posters and booklets. As a rule, we try to reach a compromise because each production can be only the result of a team effort – and I mean creative and technical personnel.”

PRODUCTIONS ARE SO FAR IN SKETCHES

ON TRADITIONS

“The National Opera adheres to classical traditions. This is easier said than done nowadays, but we’re upholding the high art tradition, this is our strong point, something truly appreciated abroad. Each our costume is a small masterpiece. There aren’t many drama companies in the West that practice large scale stage settings, props, or make hundreds of costumes with needlework and applique, rather than pea jackets and trench coats. Modern technologies are great, but they are too expensive for us because they spell not only projectors, but also experts, techies who can handle and fix this equipment. By the way, making such costumes would cost a fortune in the West, because they are all hand-made and such handiwork is far more expensive than the latest technology.”

Verdi’s Nabucco will premiere at the National Opera on March 31. How different is the stage version of director Solovianenko and conductor Diadiura from the international version of the French director, Pierre Jean Valentin, production designer Andreas Scholl (Germany), and conductor Volodymyr Kozhuhar (Ukraine) that was on the Kyiv billboards for so many years?

“Nabucco is the main hero of Verdi’s opera. The Italians gave this name to the king of Babylon who waged wars of aggression in the 6th century BC, seized Judea, ruined its first temple, and captured a great many Jews… This epic is like an oratorio. What makes this opera special is its impassionedly tragic music, one of Verdi’s best compositions, also the marvelous ensembles and choir with their captivating messages of freedom and struggle against the tyrant. The original production design (the opera premiered in 1993) relied on a white plywood pavilion background, the costumes were made using very expensive fabrics, but the impression in the audience was of the actors wearing billowing robes that often looked like huge quilted jackets. Silk and brocade were in short supply in Ukraine at the time. My heart ached as I watched those expensive fabrics being sewn in several layers, then cut through to reveal colored pieces. I would walk up to each seamstress to pick bits and pieces that I would later use for my appliques. What made that production interesting was not the stage design but the cast starring Roman Maiboroda, Ivan Ponomarenko, Valentyn Pyvovarov, Oleksandr Vostriakov, Svitlana Dobronravova, Liudmyla Yurchenko, to mention but a few. Ours is an entirely different version and I hope the audience will appreciate it.”