Everything began with fashion in the mid-1970s. Still a teenager, Londoner Phil Strongman (b. 1960) worked as T-shirt designer for Acme Attractions and Boy casual wear boutiques. Among his friends were members of the punk rock bands Sex Pistols and The Clash, who jumped from obscurity to stardom, as well as such celebrities as fashion designer Vivienne Westwood and her husband Malcolm McLaren, the Sex Pistols manager, rock stars Joe Strummer and Boy George.

From the early 1980s on, Phil worked as rock band manager, builder, DJ, journalist, and photographer. His books Cocaine (1997), John Lennon and the FBI Files (2003), Pretty Vacant: A History of UK Punk (2007), Metal Box: Stories from John Lydon’s Public Image Limited (2007), and John Lennon: Life, Times and Assassination (2010) are about the history of counter-culture and have been translated into Swedish, Spanish, Japanese, and Croatian. Phil Strongman’s first full-length documentary film was Sex Pistols’ Secret History: Dave Goodman Story (2006), but what catapulted him to fame was Anarchy! McLaren Westwood Gang (2016), also about the punk movement, which film producer Mike Wearing called “the Apocalypse Now of art documentaries.”

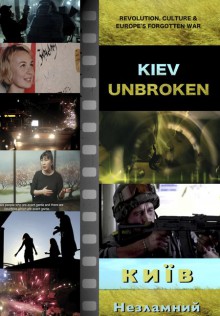

Strongman’s third film Kiev Unbroken: Ukraine Reborn (2017) is a story of Ukraine’s post-Maidan contemporary art. The characters are our new-generation artists, photographers, sculptors, and musicians, including Vlada Buchko, Roman Minin, band Panivalkova, Volodymyr Shuvaiev, Yuri Reznichenko, Serhii Shaulis, Sasha Viter, Ubik Lytvyn, and Nazgul Shukaeva. Made in the traditional manner of combining a clip, an interview, and a spot report, the film attracts you with its informativeness and the author’s unhidden sympathy with his heroes and Ukraine as a whole.

We met shortly after Kiev Unbroken’s Kyiv premiere.

LONDON – UKRAINE

So, why did the British filmmaker take interest in Ukraine?

“The original reason why I came was we were going to film a short drama, fifteen minutes. I had a big argument with the crew, and finally I said ‘No, this is more interesting – cultural explosion since the revolution.’ I thought it was amazing, as a revolution that started with young students and artists had brought down the government that had been so brutal. And I know that Ukraine always was a cultural center, but I think it has grown more, and this energy has to be captured.”

The characters of Kiev Unbroken are relatively unknown. Why did you choose precisely them?

“Yeah, the obvious thing was to choose Klitschko or whoever is the number one in the music just now. But I do not like to do the obvious thing. When I go into popular music, the Sex Pistols or The Clash, when they were starting, there were like 25 people [fans]. I think it is more interesting to me to catch someone before they are number one, when they are coming up and they are very young. I tried to capture their youth and their spirit. They were doing great work.”

What is your greatest impression of the Ukrainian revolution?

“I still think it is amazing, an astonishing achievement, that that happened. I thought that will be a little bit like Paris in 1968 or London in 1970s-1980s. I was amazed at the fact that Kyiv is a friendly city, it’s a safe city. In some ways, it is safer than London. And the quality of the music, even if I don’t understand some of the words – I mean if they sing in English, it’s easier to me – but someone sounds in Ukrainian, someone sounds in Russian, and I get the melodies, the arrangement, this is brilliant. It’s a privilege to get to know all these people. I think the fact that the crisis is continuing, that Putin wants to go on, that there is still a war – I think it gives the film this geopolitical importance.”

Speaking of geopolitics, what image is Ukraine projecting in Britain?

“I think, it has now turned, people are realizing, Britain is becoming much more Ukraine-friendly nation. I think there is a Scottish MP leader, who has just joined Russia Today television, and he has had a lot of trouble. People are going, ‘You are a prostitute! How can you do this!’ I think it’s changed in the last year, it has been too slow, but politically, England is always too slow. I think people are beginning to realize that, on one level, there is a huge cultural youth quake, that youth is doing amazingly creative things. And also, politically and militarily, Ukraine is defending European civilization.”

Have you shown your film in London yet?

“We have had no big screenings in London, and we held a free screening for people who could not come to Kyiv in a squat. There were a lot of people there, not just British, but also from France and Germany, and they were amazed – not just with the artists who were great, but also amazed about the situation. They did not know the war was still going, ‘Wasn’t there the Minsk Agreement? Isn’t it over now?’ But people loved the artists, which doesn’t often happen in London when you screen a film.”

Where is the line between politics and art for you?

“I am still discovering now what the line is that you cross. But I think I have a role to play. It can be political, it can be non-political, it depends on whether art is good. And I think the whole thing was like fascist art, like Germany in the late 1930s, if you look at that, it’s just a parody. But the good art of that time is against fascism, against Stalinism. And now artists of the world are like, ‘politics is not for us,’ but what happens here, in your city, in your country, it’s probably bad to ignore it.”

SCUM

The rest of my questions are about punk rock and punks. Were you really angry with the young people or was it sort of a show?

“It was both. It’s like Sex Pistols – fake that then became real. Malcolm McLaren, he had these three guys in this group and then he said, ‘why wouldn’t you take John Lydon?’ [lead singer of Sex Pistols. – Author] and they hated it. A normal manager would have said, ‘Let go, get him out,’ but he was like, ‘No! You are hating? Great!’ So, it was being creative. The thing England had until the 1990s, when people would not just buy clothes, they would stick a badge, or stitch something on, or rip a sleeve – it was very creative. Suddenly, the people who had 75 dollar trousers were not fashionable. It was a great moment, a flip around. There was this DIY thing – Do It Yourself – that said, ‘OK, keep it a mess.’ And it was the thing with the London police who did not like you being different, that was our way of saying ‘Screw you!’ making our statement. So it became angry.

“It was in a way the biggest mass art movement since Dada. We suddenly felt important. Why we were taken so seriously? People always overreact. You know, I mean, if Yanukovych had not sent in the Berkut to beat everyone up, beat the students on November 30, maybe things would not have happened and his rule continued as it was. I think, in a way, there is a small similarity in creative people in Kyiv. I think it will grow, and in a way, it will become in time a bit less creative, because there will be lots of tourists, which brings money, but also damages things. That’s what happens.”

It is interesting that you mentioned Dadaism, for I have an idea that the Sex Pistols was McLaren’s project based on his situationist experience, while situationism [the left-wing movement that considered artistic youth the subject of a revolution and stirred up mass-scale riots in Paris in 1968. – Ed.] directly derives from lettrism [a French avant-garde movement that became notorious for art-related provocations in the 1950s. – Ed.] which in turn derives from Dadaism. Therefore, the Sex Pistols are part of a longtime tradition of radical art.

“Yeah, it was a thing. Malcolm told me about Guy Debord, the big situationist. When ‘God Save the Queen’ was number one in England in all the charts, except the BBC chart where they made it number two, they cheated. They could not have it, because if it was number one on the BBC chart, they would have to play it on TV. So, Guy Debord said then: ‘Thank you for making my record number one.’ In a way, it was true.”

And do you agree with Lydon that the Sex Pistols did away with rock-n-roll?

“They could not save it. It was dying. By 1976, rock-n-roll became a toothless old man. Most influential rock-n-roll groups ever were the Beatles and Sex Pistols, both with an Irish connection. I mean, there were others like Pink Floyd, but it did not get thousands of groups. That was the great thing about the beat – suddenly, there were 400 groups in Liverpool area. And it was the same thing with the punk thing, the New Wave thing. Suddenly, everyone you knew was in a group. It was about possibilities. People would then, if they had gone to university, then they would think ‘I would do this thing the rest of my life.’ And then this thing appears, ‘you don’t have to play guitar that well, just try – to try is to succeed.’ And that’s a great thing to hear when you are young. It’s a great liberating thing.”

What are you going to make next?

“I still would like to do a drama film. My idea of the drama film is something like as if Christianity has not happened, and it’s in the reign of Yanukovych, about a young woman who somehow gets pregnant out of the blue and a boy who has never slept with her. I’m a Protestant Christian, I’m not a very good one, I go to the church like twice a year, but if you read the New Testament again, you realize that these are two cousins: one gives birth to John the Baptist, and the other one, Mary, is a cousin of the mother of John the Baptist, and she gives birth to Jesus Christ like a few months later.

“The other film is more documentary, which may be easier to get together. It will be about these mystical roots of Ukraine – all the things that people think in the West as being Polish or Russian, or Lithuanian – girls with the flowers in their hair, and certain drinks, and certain things, like vyshyvanka, are actually Ukrainian. My father said that Ukraine and Russia were different, even though they both were parts of the Soviet Union, so I knew that much, but I did not know the fact that Kyiv was there centuries before Moscow. And the Cossack story intrigued me, I would like to investigate that. I would like to try to shoot the modern Ukraine, but showing its ancient roots.”

HAPPINESS

Finally, what kind of experience was the making of Kiev Unbroken?

“So many things happened with this film. I mean, to me as a documentary filmmaker, in a terrible way, it’s a dream come true. But we got the Universe on our side. Maybe we were lucky. You make your own luck, and the thing is, there are so many coincidences in this film. I still think it will all have an impact. I hope it will not take that long, but even if it does, I think in 10-20 years, people will look back and say, ‘Wow! That’s a great scene! We should have been in Kyiv in 2014, 2015, 2016, 2017 and seen that, and seen these artists when they were young.’ I can feel myself lucky.”