In the company of our press photographer, I climb Kyiv’s Batyieva Hora hill, where a creative family’s little house stands out surrounded by luxurious mansions. “We have a Harry Potter-like atmosphere here,” Bohdan Polishchuk smiles. We walk through the courtyard decorated with a few sculptures – works of Olena Polishchuk’s father Oleksandr Rachkovsky – and enter the house. Behind the door with a brightly-colored lock painted on it, we find the room where the couple works. It is clear they have prepared for our visit by getting out a box of paper blanks looking like paper cuttings, a few posters, and, prominently placed, a model of the stage set for the play The Rhinos, directed by Andrii Prykhodko; the couple worked on this stage set in 2014. The play is still being staged by the Franko National Academic Drama Theater.

For the next few hours, we traveled in the fantasy worlds that emerged from the pile of sketches and other working materials. The Polishchuks do not just create the scenery, but rather translate the production’s essence, its abstract idea through material things.

BETWEEN ART AND MATHEMATICS

The artists use the computer for a lot of their work, because dozens of sketches are sometimes needed to create just one character or a scene: it is necessary to change and shuffle a lot of details to get the image one desires.

“When you meet the director for the first time and show them your first sketches, you make them beautiful to show off your skills and get the director interested. However, when you draw the 20th or 30th version, you just take a pencil, a random sheet of paper, and draw. You strive only to make your idea clear,” Bohdan told us.

Olena showed a scheme of the Franko Theater’s stage. The drawing shows its dimensions and bars to which set pieces are attached. Every idea must be tested against this scheme: it is necessary, after all, to calculate the distance between set pieces so that the light has free access, and no actors stumble. The set designer enlists the production manager’s help to achieve it.

Of course, the artist must give a lot of thought to the ways to implement their design, the kind and quantity of the material needed for this, and get ready to defend their views in discussions with the theater’s craftspeople. “Sometimes we need some piece to be robust, strong, and yet lightweight,” Olena Polishchuk told us. “For example, in The Rhinos, the actors had to jump and climb on chairs. We had some made of iron, to be strong enough, and some of aluminum, so that the actors could pick them up. Over time, the actors learned which were which, but they did get confused on a few occasions during first performances.”

WHY ILLUMINATORS ARE GODS OF THE THEATER?

Doll house-like models of stage sets are just fascinating. One wants to play with them, move about small chairs and cardboard chests of drawers. “The director perceives our model as just a beautiful piece of work sometimes. However, it gets magnified greatly on stage, lights get installed, people walk amid set pieces. And then, on the day when the stage set makes its first appearance, the director says that the model looked totally different. This is such a disappointment for the artist,” Bohdan shrugged.

“Because the model has no light, but it is actually the half of it all,” Olena continued. “That is, we see just a huge jumble of plywood on stage, lacking soul and anything else. So I like it most when illuminators start working.” Thus, the artists believe that if the gunners are often called the gods of war, illuminators should be rightly called the gods of the theater.

JACKS OF ALL TRADES

After working on the production ends, Bohdan suffers from a kind of clothing store allergy for a time. It is because he has to visit many stores and torment their managers while looking for the right stuff when creating his images.

“Usually, the theater has a dedicated fabric purchaser. But if you trust them to do it, you will not recognize your costume,” Bohdan explained. “For example, I planned a pair of gray pants to be worn by a character. However, there are many varieties of gray pants. So I spent weeks driving from one store to another and looking for the ‘right’ fabric. Perhaps no one in the audience will see the texture of the material and its stripes or something, but it affects the actor. And then, there are the fabric’s aesthetic qualities: how it looks when illuminated, how it suits the actor.”

The theater sometimes lacks craftspeople, and then the artist has to learn the trade of a carpenter or a painter. Bohdan has had to sandpaper and paint stage sets. He is lucky to have a rich imagination, because this work requires amazing tricks sometimes! “We needed a transparent sphere once,” Olena recalled. “We could not find a producer. Finally, we got two windows for helicopters or airplanes at a plant and made a sphere out of them.”

HIERONYMUS BOSCH AND A SEA MADE OF RICE

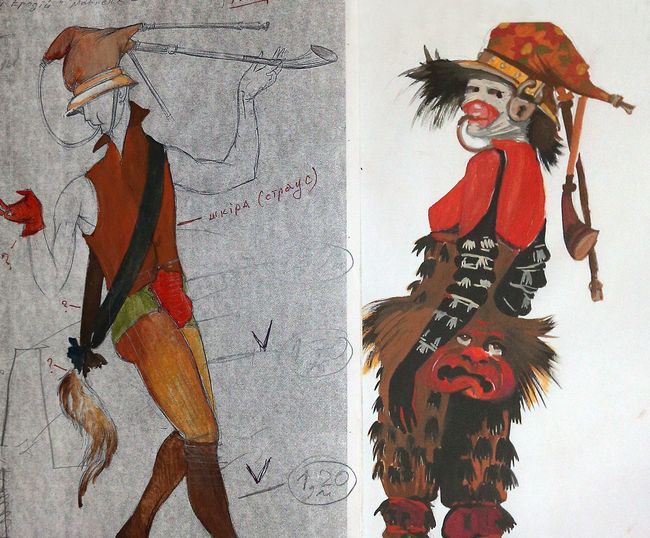

Bohdan has a few funny photos in his archive which show the behind-the-scenes details of the Grateful Erodius play (directed by Volodymyr Kuchynsky, it premiered on the stage of the Kurbas Lviv Academic Theater past year). The artist worked on it effectively for three years.

Bohdan’s sketches for Grateful Erodius show eccentric creatures. Some look like guests of a Venetian carnival, others resemble modern hipsters. “There were two protagonists, a stork named Erodius and Pishek the monkey. The director wanted to create something Bosch-like, bizarre, alchemical. We invented a monkey with its face on its ass and locks and a bagpipe on its head, because it was stupid. Then, a costume failed to make it to the stage, so its elements were assigned to several characters. Someone got a face on the ass, some other a cage with a bird on their head,” Bohdan recalled.

An interesting parallel: when staging the story of Erodius, they decided to fill the stage with rice to make it look like the sea or the desert. Simultaneously, Bohdan worked on the Holodomor-themed production The Granary (directed by Prykhodko, it is a joint project of Lviv’s First Ukrainian Theater for Children and Youth and the Drabyna Art Workshop).

“OUR PEOPLE ARE AFRAID OF EXPERIMENTS”

Like exotic birds, sketches of costumes appear from thick gray files. However, not all ideas can be implemented: some do not fit into the final design, while others simply lack the needed production facilities. “I come up with something unusual sometimes. The director likes it, and the public would like it, but there is no company in Ukraine that could do it,” Bohdan throws up his hands.

“Only two theaters make ballet tutus in Kyiv, while there is only one facility which makes hats and dyes fabrics. No private entities can make complex products,” Olena said. “Also, not all directors are ready for abstract theater productions. We have either Soviet-flavored realism or documentary theater, while all kinds of avant-garde are something extremely rare. We need various types of theaters, but our people are afraid of experiments.”

Besides these challenges, others emerge, more permanent in nature: politicians do not promote culture issues in their manifestos, businesspeople do not invest in this sector, and society itself does not urge support for it.

TELLING CHILDREN ABOUT THE THEATER

The Polishchuks do not know themselves what their next production will be like. Intentions are there, but their crystallization into some concrete design can take a few years. Meanwhile, the artists illustrate books, organize exhibitions, and design print works. Olena works at the Museum of Books and Printing of Ukraine as well. “The theater artist’s task is the organization of space. This profession stands at the crossroads of it all,” the artist believes.

The Polishchuks have been publishing the independent theater magazine Koza since 2009, which is supplemented since 2012 by the children’s theater magazine Shaleni Koziulky. The magazines, highly artistic in design, are published irregularly, for it requires a lot of effort and money, after all. The latest issue of Koza was released back in 2013, and that of Shaleni Koziulky in early 2015. But the artists have not abandoned this project and are slowly gathering new content for it.

“We will offer something new of this kind. Maybe we will reformat the magazines somehow,” Bohdan promised. “One should enjoy one’s work. When you like what you do, everything comes out well. It should be one’s natural work, as Hryhorii Skovoroda would put it.”