This is a saga of the flourishing and subsequent destruction of a powerful artistic movement that arose in the 1920s-1930s in Kharkiv, then the capital of Soviet Ukraine. The 66 apartments of the “Slovo” House were occupied by our best-known writers, poets, painters, directors, and actors. The list of the residents sounds imposing: Mykola Khvyliovy, Maik Johansen, Pavlo Tychyna, Natalia Uzhvii, Volodymyr Sosiura, Ostap Vyshnia, Oles Kurbas, Mykhailo Yalovy, Ivan Bahriany, or Raisa Troian. The intellectual elite of the UkrSSR was specially gathered in one place, only to be shot, imprisoned, or forced at gunpoint to become the party’s puppet singers.

The script of “Slovo” House is written by Taras TOMENKO (who also directed the film) and poet and this newspaper’s steadfast author Liubov YAKYMCHUK. They only used documentary materials, formerly classified photographs and newsreels from the archives of SBU, research institutes, and universities. The combination of direct speech of the artists’ and their relatives, NKVD officers, party leaders, and secret police agents is woven into a complete and emotional dramaturgy of the movie.

Internationally, “Slovo” House premiered at the 33rd Film Festival in Warsaw. Its Ukrainian premiere was in Kharkiv, the city where the story unfolds. After the movie came out, the film crew set out on a tour across Ukraine. Later, the movie will be available as part of educational screenings at schools, libraries, and movie clubs.

The Day interviewed Liubov Yakymchuk and Taras Tomenko about their work on “Slovo” House.

LIUBOV YAKYMCHUK: “IT IS A STORY OF RENAISSANCE, NOT A STORY OF SHOOTINGS”

How was your movie born?

“Me and Taras, we were writing a feature script; this triggered the rest. We had assembled so much material that we decided to make a documentary. Our research took a couple of years, since late 2012. We worked at the SBU archive, where some cases were only recently declassified. For instance, the case of Maria Sosiura, Volodymyr Sosiura’s wife, known by her NKVD alias as Murka, or the case of Ostap Vyshnia, a.k.a. ‘agent 018,’ or many other documents concerning Khvyliovy, Semenko, Johansen and others. We also relied on the archives of the Institute of Literature, the archive of St. Sophia of Kyiv, the Architectural Archive, the archives of the Shevchenko Theater in Kharkiv, and the repositories of the Kharkiv Literary Museum. We had a very expert consultant Iryna Tsymbal, who gave us tips where to look for what. Also, we got help from other researchers or the writers’ relatives. By the way, even before the work on the movie started, when I had written an article on Semenko, his nephew Marko Semenko contacted me, and we also made use of his family archive. Unfortunately, we had to cut a lot of material. The script was reduced from 450 pages to just 45 and was based first and foremost on the eyewitnesses’ direct speech: reminiscences, denunciations, extracts from works. The voices of the executioners also sound in the movie, we were able to find them thanks to the priceless gift made by Tetiana Pylypenko of the Kharkiv Literary Museum. She showed us the handbooks used by NKVD officers. We studied the system from within, and did not invent anything of our own.”

Are you pleased with the artistic results?

“‘Slovo’ House is a documentary created by the rules of a feature movie. It has a conflict, but there are no talking heads; it has action dialogs recorded by actors to make the movie interesting for the audience and at the same time to keep it interesting for experts in literature or history. I guess the result is both accessible and deep. It disclosed visual and textual information which had been concealed.”

From your viewpoint as the script writer, what is this story actually about?

“The protagonist in the film is the ‘Slovo’ House self. It is the history of a house with all of its dwellers, diversity, noise, and happiness turning into hell. When it starts striving to exterminate its inhabitants, which is in fact exterminating itself. The house transforms into a prison, devouring its own lodgers with the help of wiretapping. Characteristically, it was done not only by technical means: writers and the wives of writers informed on the neighbors as well, and we show how it was done. Importantly, death did not overshadow their lives. Those people had a fun life, full of nice surprises. The public smiles through the most part of the movie. That is, it is more a story of renaissance, not a story of shootings.”

What struck you most during the work on the movie?

“Often the dwellers of the house, who knew an arrest was inevitable (some – like Anatolii Petrytsky – had had preliminary visits), just sat still and did not even try to put up a fight or at least escape. They did not have full information yet, they did not know they were going to be shot, but those arrests alone, and them becoming outcasts and their families kicked out onto the street, all that was quite enough to give some food for thought and make them try to offer some sort of resistance. Yet they were totally taken aback. And this is what astonishes me: the inactivity and licensing an own destruction. I am very happy that contemporary Ukrainian society belongs on a different level, it has learned to fight government back when it goes too far.”

TARAS TOMENKO: “THEY ARE NOT VICTIMS, THEY ARE THE WINNERS”

Taras, whence your interest in particularly that period and location?

“Because it is unique history. It started in 1929, when writers decided to pool their resources to build an apartment block for themselves. It was around the time of a Russian-Ukrainian literary scandal, when Gorky did not allow to translate his novel Mother into Ukrainian saying there was no need to publish it ‘in the Ukrainian dialect.’ To appease the situation, our writers were invited to Moscow to meet Stalin. It was the first ever trip of Ukrainian authors to Moscow on such a high level. Ostap Vyshnia jumped at the occasion and asked for some money to finish the construction. In the evening several NKVD officers knocked on his door. They brought a sack of cash. Actually, this was the money that helped complete the ‘Slovo’ House.”

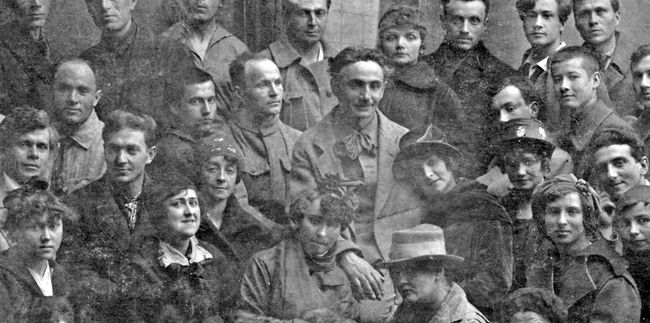

LES KURBAS WITH HIS PUPILS AND COLLEAGUES AT THE ART NOUVEAU THEATER “BEREZIL” IN THE 1930s

The apartments were distributed by government.

“They drew straws. Sometimes it got real comic, when writers could swap apartments. For example, Maik Johansen ended up above Pavlo Tychyna, but Johansen had dogs who pounded with their paws. So the two had to swap as Tychyna could not bear that racket. By the way, we found unique records of Tychyna’s and Volodymyr Sosiura’s voices and photos of the writers which had never been seen before. Most Ukrainians have no idea what they all looked like. The public will see all that for the first time.”

How would you describe the form of your movie?

“It is based on the principles of mosaic, arabesque, and collage. We took archive materials – investigation cases, interrogation notes, denunciations, parts of books – and laced it together to help the viewer sense the atmosphere of the house.”

But atmosphere depends on people…

“They were all incredibly intelligent. Johansen could learn Serbian during dinner, in a couple of hours, and he read Knut Hamsun in the original. International attention for Ukrainian literature was enormous too, the conference of proletarian writers in Kharkiv was visited by Bertolt Brecht, Theodore Dreiser, Bruno Jasienski, Henri Barbusse – and they all visited the ‘Slovo’ House. Yet we do not show the inhabitants of the House as bronze idols from school textbooks. On the contrary, we portray them as young, full of energy and imagination, real creators of a new language in art. Les Kurbas, Mykola Kulish, Anatolii Petrytsky, Vadym Meller: an entire constellation of Ukrainian Renaissance gathered under one roof, a unique occurrence in history. But this became also the reason why the place came to be known as the House of Preliminary Detention. It had all amenities, even a sun parlor on the roof and was complete with kitchens and dining rooms: everything to allow writers to work and create undistracted. And somehow this cozy paradise turned into hell. The walls had ears. By wiretapping everyone the regime wanted to reveal the measure of their talent, as it needed ingenious minds to recruit them, and it probed for their weak spots. People became informers, there were even entire manuals for that.”

Don’t you have a protagonist?

“No. Historically, Mykola Khvyliovy, with his drama, was the key figure at the ‘Slovo’ House. A romantic singer of the revolution, carried away with new ideas, he learned about the Holodomor and decided to go and see for himself; together with Arkadii Liubchenko he set out on a secret tour of the countryside, with a mission from the editorial office. Khvyliovy saw it all and was horrified. Upon his return, he gathered his closest friends and shot himself in the head. He sensed the inevitability of the imminent disaster. After that arrests and slaughter began.”

This whole story is actually palpably disastrous.

“But we will consciously refrain from reducing it all to the term ‘the Shot Renaissance’ because of the negative charge it carries. Our characters are heroes who remained immortal in their works. They gained a worthy place in the history of world culture, they are our invaluable heritage, and this is the perspective we made the movie from. They are not victims, they are the winners.”