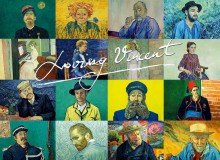

The first thing that attracts your attention in the film Loving Vincent is, of course, the technique of execution. The work of the Pole Dorota Kobiela (scriptwriter of the fairytale The Flying Machine, 2011) and the Briton Hugh Welchman (Oscar for the best animated short film Peter and the Wolf, 2007) is the world’s first full-length animated movie fully drawn with oil paints. A team of 85 artists (including some Ukrainians) did all the 62,470 frames in oil on a canvas in the same post-impressionist manner in which Vincent van Gogh worked.

The protagonist is Armand (Douglas Booth), the son of postman Joseph Roulin, a hot-tempered but sincere boy with a strong feeling of justice. At the beginning of the story, father asks Armand to deliver van Gogh’s last letter to some of the painter’s relatives (it was addressed to his brother Theo, but he was also dead). Armand comes to the town Auvers-sur-Oise to find Vincent’s close friend doctor Gachet (Jerome Flynn). Waiting for the latter to come back, the postman meets a lot of people who not only knew van Gogh and the circumstances of his death, but also appeared on his pictures.

Biographic films about well-known people often “suffer” from excessive melodramatics and simplified plot-related techniques, when, to shape the story, scriptwriters try to find a conflict in the life of a hero or heroine, showing the finesse of gutter-press journalists and putting the blame on each and every. The authors of Loving Vincent also rely on a biographic material. However, even introducing some elements of detective investigation, they still leave it to the spectator to answer the question about the cause of the artist’s death (suicide or unintentional murder?). Everybody is guilty of something, but nobody is guilty in essence. The permanent source of Vincent’s misfortunes is not the hypothetic mental abnormality but his very nature and gift – too challenging to the surrounding reality.

Interestingly, Vincent passes as a secondary character, mostly in black and white flashbacks. This detachment, coupled with the equality of various voices, views, and versions, make the film’s style fully justified or even the only possible. People on the screen speak about van Gogh and argue whether he was a genius, but all this occurs in the world he created.

And this metaphor also applies to us. We are also, in a way, the creatures of Vincent – on paintbrush tips, lovingly.