Russia has found it necessary to teach schoolchildren the most contemporary history, including the events connected with Russia’s annexation of Crimea and the Donbas war. So far, the school curriculum provides for teaching the history of Russia up to 2008 only, including the war against Georgia. And now, at the seminar “Strategy for the Future,” schoolchildren allegedly suggested taking lessons in Russia’s contemporary history, and Federation Council Chairperson Valentina Matviyenko fully endorsed this idea.

Knowing Russian realities, we should not doubt that the initiative is by no means coming from the grassroots, i.e., schoolchildren and teachers. The simple truth is that the new education minister and the president’s chief of staff are examining the reaction to the likely introduction of lessons in the past few years’ history inside and, particularly, outside Russia under the guise of suggestions from the broad school masses. What is more, there already is a state-sponsored project “Lessons in the Contemporary History of Russia.” The project manager, Stanislav Neverov, is sure that the question of Crimea, the Donbas, Syria, sanctions, and countersanctions should be included. “The populace does not understand why we did it in Crimea failed to do it in south-eastern Ukraine. As people have questions, we should explain things to them from the historical angle – why, which territories, and so on. The school cannot explain this today because there is no proper educational standard today, while the textbook embraces the time span until 2008 only. Teachers are, to put it roughly, ordinary ‘people in the street’ who, like their pupils, watch the 1st Channel and Russia TV and believe what they see; then they switch to a more oppositional channel and also believe what they see. This brings muddle to their heads, and, as a result, they can’t possibly form an opinion of their own” (http://novosti.dn.ua/news/262500-v-rossyy-na-urokakh-ystoryy-rasskazhut-...), he said.

As for oppositional channels, Neverov found a mare’s nest. The only oppositional channel Dozhd has a scanty audience. So, in practice, the schoolchild can choose between Russia TV and the 1st channel only, which show no difference in covering the Crimea and Donbas events.

Of course, Russian schoolchildren have a legitimate right to know what has been going on in their country in the past few years, why Russia annexed Crimea, and why the Russian military and volunteers are fighting in the Donbas and Syria. All this will be some day a very compelling lesson for national repentance. It will be good if pupils come to know how Russian “little green men” appeared in Crimea, how they used women and children as human shields and organized a referendum at gun point. They will know to what extent legitimate this referendum was from the viewpoint of international law. They will know that Russian pilots and commandos are defending a brilliant regime of Hafez al-Assad. They will come to know about the exploits and destiny of “Batman,” “Motorola,” “Givi,” and other Russian World heroes. They will ponder on who downed the Malaysian Boeing over the Donbas and on why mortality in Russia, which has been steadily falling in the past few years, suddenly jumped up by as many as 26,200 people in the first half of 2015, only to resume diminishing in the third quarter up to this day. They will try to learn what epidemics, earthquakes, floods, and other natural calamities Russia experienced in 2014-15 in addition to the Donbas war, as well as to reflect on what war crimes are and what responsibility the aggressor country and its people bear for them. But, in reality, it will take us a very long time to see this kind of honest school lessons in Russian history.

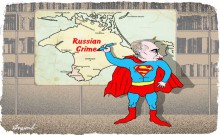

What is now being planned in Russia under the guise of “contemporary history lessons” is certain to have the style of the Solovyov-Kiselyov television in the spirit of such slogans as “Crimea is ours,” “Let’s avenge the crucified children of Sloviansk,” “Russian spring,” and assistance to “our Russian brothers in the Donbas” and “the legitimate government of Syria.” It will also be in the spirit of a struggle against the “Banderaites” in Ukraine and “American hegemonism” all over the world. At the same time, they are going to describe Russia’s radiant future under the leadership of Vladimir Putin and as a result of implementing his program “Strategy 2020.” It is no accident that the project is supervised by Andrei Khudoleyev, secretary of the Presidential Council’s commission in charge of informational coverage of governmental policies. Very soon, teachers and pupils in Ivanovo, Leningrad, Tomsk and Tyumen oblasts, Kamchatka, Kabardino-Balkaria, Crimea, and Moscow will have a happy chance to see these lessons “on an experimental basis.”

Should the experiment be considered successful, lessons in contemporary history will be introduced compulsorily in all the schools of Russia. It is beyond any doubt that these lessons will be conducted in the spirit of great-power chauvinism and xenophobia, when President Putin’s policies will be fully justified no matter what he may do today or in the future. The Russian opposition that came out on Bolotnaya Square, as well as the Euromaidan in Ukraine, will be discredited in any possible way. And the teachers who will refuse to speak out the Kremlin’s propaganda and instill hatred towards the neighboring nations in children will have to resign.

Naturally, this interpretation of contemporary history (and there will be no other interpretation under Putin) will stir up outspoken discontent on the part of Russia’s neighbors. But the creators of “contemporary history lessons” are not worried at all about this. Like the Kremlin, they adhere to the “good old” principle: let them hate us, but they must be afraid. I think this kind of lessons are supposed to show to Ukraine and other post-Soviet states that Putin’s Russia will build its relations with them on the principle: your are to blame just because I am hungry. Children will be told that Russia wants to be friends with all of its neighbors, and if some of them do not want to be Russia’s friends, they do so under American influence. Schoolchildren are very likely to be forced to believe that all peoples of the former USSR do nothing but dream of reuniting with Russia in a new fraternal Union, but some venal politicians on the West’s payroll are thwarting this dream.

In the conditions when the younger generation of Russians is forming this picture of the world, they will find it very difficult to have a dialog with the neighboring nations. But the Kremlin just hopes to cultivate besieged-fortress mentality in the populace. Let them listen to the father president instead of thinking of a dialog with “Banderaites”! And there will be no Maidan in Russia then!

Boris Sokolov is a Moscow-based professor