“The circus day,” as oppositionists call parliamentary elections in Belarus, has occurred. Compulsory voting by students, soldiers, and civil servants; mass-scale casting of “doctored” ballots, a bizarre “merry-go-round” of small groups of “comrades” who seem to sleepwalk across polling stations; and just a “funny arithmetic,” when figures change – this is how observers describe the expression of popular will in the country Aleksandr Lukashenko has been leading for 22 years, including 19 when he has wielded absolute power. There was no surprise this year either – except for the fact that, for the first time in the past 20 years, two opposition candidates made their way to the Belarusian parliament. But this will not change the country’s political landscape.

The Day spoke to Professor Stanislav SHUSHKEVICH, Chairman of the Supreme Council of Belarus in 1991-94, about why authoritarianism became possible, whether there were “death squads,” how politicians and society reacted to Russian invasion of Ukraine, and whether a nation state can be restored. It is he who organized the first and last democratic elections in 1994 which brought Lukashenko to power. Shushkevich was dismissed as Supreme Council chairman on a trumped-up charge of “stealing a box of nails for building his country house.” Now he leads the party Belarusian Social Democratic Community, but he says he keeps clear of the “farce called elections.”

This is the last of the three interviews with the signers of the Belavezha Accords. Also read our conversations with Gennady Burbulis – “On Responsibility of Russian Elite” (The Day No. 46, August 18, 2016, and No. 47, August 23, 2016), and with Leonid Kravchuk – “Having Made History, We Cannot Get Our House in Order” (The Day No. 49, September 6, 2016).

“IT WAS POSSIBLE TO RIG THE 1994 ELECTIONS, BUT I AM A FIRM ADHERENT TO A RULE-OF-LAW STATE”

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Belavezha Accords. What do you feel a quarter of a century later?

“I still feel proud of what we did. And while it is not allowed to openly express your opinion in Belarus, I find support and respect in the other countries I visit, including those of the former ‘socialist camp.’ I have found that the ratio of positive and negative emotions is an estimated 20 to 1. In other words, one of 20 is sure to say: ‘You wrecked such a country!’ Curiously enough, those who take and try to defend a negative attitude have, as a rule, never read the Belavezha Accords and don’t know what they are all about.”

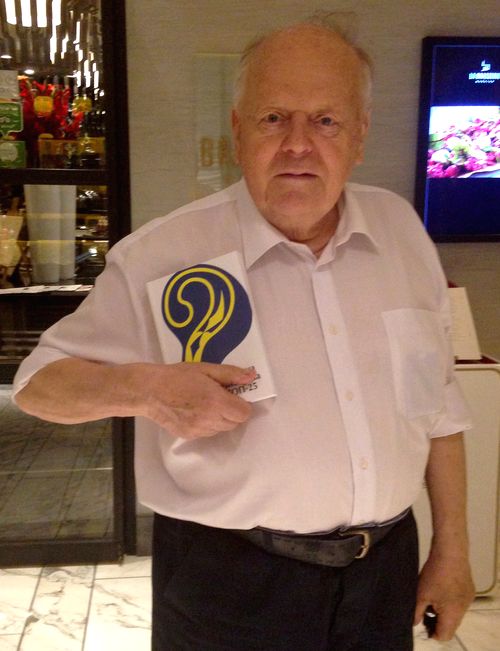

DEN PRESENTED STANISLAV SHUSHKEVICH WITH ITS LIBRARY’S BOOK UKRAINE INCOGNITA ON 25 KEY MOMENTS OF UKRAINIAN STATEHOOD. SHUSHKEVICH IN TURN CORDIALLY WISHED US LONG YEARS OF PROSPERITY IN CONNECTION WITH OUR 20th ANNIVERSARY / Photo by the author

When you were signing the agreement on dissolving the USSR, you must have been thinking about what will happen 10, 20, or 30 years later. Do you think today that sliding back to authoritarianism was inevitable or it is an aberration of the sociopolitical development?

“There was and still is a specific situation in Belarus – the concentration of pro-Soviet communist-minded people here is even greater than in Russia. Belarusians are credulous: they once believed Lenin’s slogans and are now unaware of many things. For this reason, the old party nomenklatura, which accounted for 82 percent of Supreme Council members in 1991, felt very confident due to their dominant Soviet persuasions. They elected me chairman in a state of fear after the August putsch. They were afraid to admit that they were supporting and wanted to show being ‘democratic.’ As I was neither in the Communist Party nor in the Belarusian Popular Front, I was a suitable figure. They thought they would manage to shape me in their spirit.

“As for Lukashenko, he embodied Soviet-style aspirations with support from Russia. The elections that catapulted him to the presidency were really democratic. If I had cared about my personal wellbeing, I could have rigged them – it was a piece of cake. But I am a firm adherent to a rule-of-law state, and I am convinced that elections must be fair. The first attempt to dismiss me as Supreme Council chairman was made in the summer of 1993, but [my opponents] were short of six votes. I dissolved parliament as I had the right to do so, everybody went away, and I used this time to take a number of important steps. Above all, it was the visit of the US president to Belarus. Before that, Belarus had not been much spoken of in the world, nobody knew anything, but, of course, all the media spotlighted Bill Clinton’s arrival. He came on January 15, and I was dismissed as soon as January 22.”

But, on the other hand, the Lukashenko era may be a transition to the nation state – a transformation cushion that prevents Russia from taking active aggressive actions. For example, Todor Zhivkov, the most loyal friend of the USSR, had ruled Bulgaria for 33 years, but he was softly removed in 1989 by the opposition which carried out a political and economic liberalization. The non-provocative nature of his 30-year-long rule allowed the country to while away an unfavorable historical time and painlessly gain independence. Is this scenario possible in Belarus?

“I agree to this example and can also add the positive consequences of the authoritarian regimes of Augusto Pinochet and Antonio Salazar. In other words, it’s not always bad to have one leader for years. But, unlike in the Belarusian case, they were highly-educated and knowledgeable people. Lukashenko, unfortunately, has nothing but experience of Soviet-era collective farming. He will betray anybody to retain power.

“For this reason, he has benefited for a long time from playing up to and serving the interests of Russia. There were even ‘theatrical shows,’ when, for example, [Russian Premier] Chernomyrdin solemnly tore out a boundary post between Russia and Belarus. Of course, Russia’s rulers find it easier to deal with one omnipotent president than to allow the development of parliamentarianism, when all decisions are made public. What is more, Lukashenko is so loyal to the idea of a united state that he once believed in the possibility of becoming president of Russia – he used to campaign in the regions and speak seriously to governors. So, unfortunately, the scenario of Bulgaria and some other countries is not for us. For, in this case, one must know what politics, power, and national interests are.”

“THE SOVIET MENTALITY OF MANY ORDINARY BELARUSIANS JUSTIFIES THE INVASION OF THE CRIMEAN PENINSULA”

In what way did Belarus react to Russia’s aggression against Ukraine?

“Lukashenko himself says: ‘I favor Ukraine’s territorial integrity. And Crimea belongs to the one who owns it de facto.’ These statements contradict each other and common sense. We have a communist party, ‘A Just World,’ which has openly stated that it supports the invasion of Crimea. They interpret geopolitical reality in their own, Soviet, way. It’s difficult for me to assess societal sentiments in percentage points, for there have been no public opinion polls. But, as for the opposition, intellectuals, and educated adherents to a rule-of-law state, whose number is in fact quite large in Belarus, they, naturally, oppose and do not accept ‘Russian Crimea.’ But the Soviet mentality of many ordinary Belarusians justifies the invasion of the peninsula. What is more, they know history fragmentarily and have never heard about the deportation and genocide of Crimean Tatars and other eloquent facts. This is hushed up.”

In Ukraine, the murder of journalist Gongadze triggered protest actions that resulted in the Orange Revolution. In Belarus, “death squads” held sway – some prominent businesspeople, politicians, and journalists disappeared and were not found. Why do Belarusians keep silent?

“There really were ‘death squads’ in Belarus, for the authorities couldn’t do without them. There was to be a professional group to carry out abductions. Two most charismatic leaders disappeared – this could not have happened without the knowledge of secret services and personal approval of the president – I know it quite well.

“Belarusians used to stage protests, only to face a harsh, all-round, well-thought-out, and provocative crackdown. I have no doubt that it was launched by those who know how to fight against protesters. I must say that political repression is organized very well in our country. It involves a considerable force. In Belarus, there are 1,452 policemen per 100,000 of the population, while they are 5 and 10 times fewer in Poland and Finland, respectively. It is therefore easy to launch a crackdown in Belarus.”

Does it mean that democratic gains have been largely nullified in Russia and Belarus?

“Yes, by contrast with, for example, Ukraine. You have a very strong principle of electiveness for the government and, hence, more chances to emerge as a successful independent state. It also seems to me that the lasted events showed a considerable cohesion of society.

“I cannot see or expect any changes in Belarus because, above all, Russia has long been supporting this regime, especially by way of oil and gas prices. Russia annually invested 12 billion dollars in Belarus until 2006. Then the former began to reduce its infusions, but it extended new loans to the latter – either its own, or Eurasian, or someone else’s. Incidentally, the IMF was also giving Belarus a loan, but its conditions were not fulfilled. The Belarusian authorities maneuver and lie all the time.

“I can see no major foreign threat to the leadership because Europe is not interested in its center being unstable. This graveyard-like, harsh, and mean stability of ours suits Europe. It is very difficult for the opposition when Europe adheres to Realpolitik – you must interact with the existing leadership and be guided by benefits. The fact that Lukashenko was de jure banned from Europe did not prevent him from visiting other countries as a private person.”

“IT IS IMPORTANT AND NECESSARY TO BUILD A CIVIL TYPE OF POLITICAL CULTURE”

What do you, a person who headed the Supreme Council at a critical time, think of the role of parliament in the state?

“Parliament is a profile of society if it has been elected fairly. Under a viable up-to-date constitution, parliament is a purely legislative body that interferes into nothing. But the Soviet system was different. A constitutional clause allowed the USSR Congress of People’s Deputies to consider any question and pass the final resolution on it. What does the Soviet slogan ‘All power to Soviets’ mean? It means concentration of all kinds of power in the same hands. It is a bad structure, and it has had an impact on the parliaments of almost all the post-Soviet countries. In Russia, the United Russia party has become a new CPSU, and the election process is ineffective there in principle.

“If we managed to achieve a high level of parliamentarianism, comparable to the situation in Lithuania, Latvia, and particularly Estonia, parliament would become a very important position. In many post-Soviet states now, it plays a ‘mobilizing’ and propagandistic role, but it is not decisive or constructive. The decisions made by a ruling individual can be fulfilled faster. It is not always bad, for if he or she is patriotic and highly educated, this may produce positive results. But still it is important and necessary to build a civil type of political culture.”