(Continued from the previous issue)

In the first interview (see The Day’s No. 71, November 24, 2016), Dr. Andrii BAUMEISTER, associate professor, Faculty of Philosophy, Taras Shevchenko National University of Kyiv, commented on the topicality of Aristotle’s idea of common good for Ukraine and Donald Trump’s victory as the end of virtual democracy. This time he shares his ideas about the age when one should take up philosophy, the therapeutic effect of self-education, and the harm of self-evidence.

Dr. Baumeister, over the past couple of years there has been an increasing public interest in philosophy in Ukraine, with university lecturers becoming public persons, appearing on television and at roundtables. What do you think is needed to keep such discussions on a high professional level?

“Running serious tests within our society, which is just taking shape and isn’t accustomed to the culture of debate. Take the United States or Great Britain. Their high school students are taught this culture. In our schools the students are taught to sit at their desks, back straight, and listen to what the teacher has to say. Here the schoolteacher is treated as either a guru or a pain in the neck. Here we have polarized attitudes and no culture of debate.

“Therefore, one has to start by establishing certain requirements within society, so people can voice certain ideas. We watch lots of ‘philosophers’ on television, among them futurologists. Our philosophers tend to be very delicate, they are not used to making statements that reflect the reality. They do not seem to realize that certain topics can be of interest to their audiences, even if not pertaining to their profession.”

NO NEEDS OTHER THAN PROFESSION

Could one regard you as a follower of Thomas Aquinas, as a neo-Thomist?

“Now that’s a bit on the provocative side. I do think that Thomism is close to modern analytical philosophy, but I’d rather describe myself a follower of analytical philosophy. Let me explain. In the early 20th century, there were phenomenologist, Kantian, and existentialist schools and those affiliated simply could not discuss important contemporary topics, because a phenomenologist would say that his school has this view on the matter and a Kantian would counter that his school has a different view. In analytical philosophy schools make no difference, with people coming up with ideas and arguing their points, and with philosophers proving them right or wrong. Today’s philosophy is above the schools, allowing us to seriously discuss important things. In this sense, my Thomism is a bit on the pretentious side. Philosophy is important to me as practice, as an experience, as a school of rationality where one learns to think clearly and prove one’s point in no uncertain words.

“What is the role of philosophy in this world? If you have a razor sharp analytical mind, you can explain complicated problems. In reality, few people can clearly see a really complicated problem, because it takes years of practice polishing the culture of thinking. This is the philosopher’s calling.

“In my latest monograph ‘Being and Good,’ I wrote that the discourse of interpretation is prevalent here. There are good and very bad interpretations (the latter make up 80 percent). We retell someone’s books, but there is no investigative discourse, whereas research is the main task of philosophy. This is easier said than done, considering that our academic community is too busy reading lectures and conducting training courses. As a university lecturer, I’m well aware that this system leaves no room for research; there is simply no time for it. I do research in my spare time. I can’t afford the luxury of an idle weekend, and I have no needs other than my profession. To live that way, one has to deny oneself certain benefits of life and adopt a degree of asceticism. I rejoice in scholarly accomplishment, philosophy is my life, but this is something few are prepared to accept on a daily basis. My colleagues in the West have their sabbaticals, each lasting a year, granted after three or four years of academic work. They teach two days a week and have four days for individual research. They can use this time to write books and read public lectures. In Ukraine, we are like schoolteachers, conducting classes, reciting others’ ideas.”

LACK OF BOOKS ON PHYSICS AND BIOLOGY IN UKRAINIAN

Still, you have been publishing another book approximately once every 1.5 years.

“That just happens, and I’m not sure it is on a regular basis. I’d like to use this occasion to thank the Aquinas Institute for the Study of Sacred Doctrine (I’m a lecturer there) for their financial aid courtesy of certain foundations; also, the Ukrainian Catholic University that helped my colleague Rostyslav Paranko and me publish Anselm of Canterbury’s Monologion and Proslogion in Ukrainian with a parallel text in the original Latin. Anselm was a Benedictine monk, abbot, philosopher, and theologian of the Catholic Church, the originator of the ontological argument for the existence of God and of the satisfaction theory of atonement. These editions are of top quality in terms of print and makeup. I wrote an extensive foreword, commentaries, and was the scientific editor.

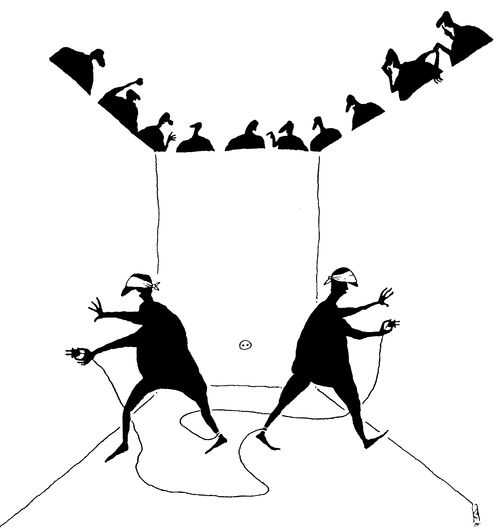

Sketch by Anatolii KAZANSKYI from The Day’s archives, 1997

“Such projects can be carried out only with financial support [from outside] and we have to get used to the idea that science in Ukraine needs this support. A scholar can’t sit up nights writing for himself. We still don’t have a book market, just as we don’t have enough bookstores. There are several in downtown Kyiv, but there are few books on the natural sciences, mostly humanitarian publications. I specialize in the philosophy of consciousness associated with the natural sciences and there are practically no books on physics and biology in Ukrainian. This is a complex problem, considering that one can only count on publishing a bestseller.”

You wrote on your blog for Den/The Day that philosophy has no age or professional restrictions, that it has to be taught in high schools. How can this be achieved in a comparatively simple and interesting way? Where to look for philosophy teachers?

“This is a problem that also reflects social self-understanding. There is a degree of public distrust of schoolteachers – probably with reason – and the same is true of physicians, politicians, experts as a whole. Philosophy should be taught by interested charismatic individuals. Philosophy doesn’t have to be taught in all schools. In Italy, Austria, Germany, and France, it is taught to senior high school and lyceum students, and those who teach it are personalities, authors of scholarly papers who know how to deal with children.”

SCHOOL STUDENTS’ EXISTENTIALIST QUESTIONS LEFT UNANSWERED

What kind of high school can interest such charismatic individuals?

“We must have experimental high schools, even universities. There is a private university in Ankara where the instruction is in English. It is funded by local Turkish oligarchs. In China, every effort has been made for some universities to rank with the Top 100. They have been actually buying leading European lecturers. Or take Russia’s Higher School of Economics. Ukraine also needs several such model super-schools and super-universities, even though almost every high school in Kyiv claims elite ratings. Such institutions of learning must have the best teaching staff. We must have institutions that can serve as examples worth emulating.

“Philosophy should be taught starting at 15-16 years of age. It is at this age that the young individual starts formulating philosophical questions. If such existentialist, fundamental questions are not answered, they will stop being posed. Who can all these boys and girls trust to answer their questions? Are there classes during which they can discuss such things? Previously, there were literature classes, but now literature is taught in a very dry manner, with the emphasis on recital, without writing compositions. There are no subjects in the high school curriculum to help the students learn to think, write, take part in a debate, and express their creative self. That’s where philosophy steps in – and if some don’t like the word ‘philosophy’ they can find another appellation.”

LIVING AND LEARNING

You have a book in the works. What is it about?

“It’s an initiative supported by the Small Academy of Sciences. First, I promised to write a book entitled something like ‘Philosophy for Dummies,’ but as I started on it, I realized it wouldn’t be for dummies. I ended up writing for any educated reader aged between 17 and 90 plus. Each chapter has two parts, one for the general public and the other for experts. I wanted to spark the reader’s interest in philosophy and demonstrate its attractiveness in coping with various problems. Back in the 20th century, a number of physicists and mathematicians wrote books dealing with philosophy. They felt they needed to cope with philosophical issues.

“My cherished dream is a book on philosophy for children, but this project would apparently take more time. Writing for children is more complicated, you have to study their psychology. You have to make short and precise statements, provide graphic examples, and use colorful modern illustrations. Some achievements made along these lines in Ukraine, owing to the cooperation between the Drahomanov National Pedagogical University and the Small Academy of Sciences. I believe it is high time such projects were carried out.

“I took up philosophy at 13, inspired by reading books. Good books were in short supply in the early 1980s, so I decided to write one about a hero traveling to Shambhala, meeting Mahatma sages, then sharing his wisdom with the world. As I wrote, however, I realized I couldn’t formulate that wisdom, that I had to study philosophy. I began reading books on the subject and discovered I understood practically nothing.

“In fact, the first time you read a book on philosophy, you’re shocked by being unable to make head or tail of it. This is only natural. One can’t possibly understand Kant, Spinoza or Marx at 13, but this experience is necessary. If I wrote a book on philosophy for children, I’d refer to philosophy and other things. Movies, fiction literature, poetry, art can help the reader reach this level, it’s like having to climb another couple of rungs up the ladder to reach the top.

“Modern studies show that the traditional education system is becoming extinct, considering that people often enroll in universities and find out later that they made the wrong choice. Our brain is designed so that we have to learn for as long as we live. This requires the development of certain skills that can motivate us to constantly develop ourselves. I am convinced that this is what philosophy has to do. Philosophy teaches us to see that there is actually no self-evidence, that what we tend to accept as self-evident can cause serious problems. Philosophy is an amazing culture of self-education and criticism addressing that which appears to be self-evident.

“Neurophysiologists insist that this approach serves to protect man against afflictions such as Alzheimer’s disease (regarded as the disease of the future). Self-education produces a physical therapeutic effect. People who stop developing themselves after retiring do not know what to do with themselves. They often give up struggle quickly, suffering from depression. They are no longer meaningfully engaged in the world around them.

“If you explain to one that university is just a stage in one’s life, that one can change jobs every five to six years, s/he is sure to behave differently. Professions keep changing; even as one is trained for a certain occupation, it may vanish from the job market. One has to keep mastering new skills.”