History is a powerful mechanism of integration, perhaps the most powerful of all that humankind has ever devised. For this reason, history has always been a compulsory subject in educational curriculums. Thrilling historical subjects allow schoolchildren to meet the realities of a world that is broader than the one they knew up to now – the world of a family or a lineage. There is no other equally effective way to introduce a little human being into the world of social and political cohabitation.

It is not only educators who use the integrative potential of history. Politicians are also well aware of its effectiveness. It is no accident that Marxists relied on the Marxist concept of history in their propaganda. Its central dogma was that class struggle is the main motive force and content of history. Accordingly, integration into the worldwide historical process was possible, above all, through taking part in this class struggle – of course, on the side of the victorious vanguard, the CPSU.

Such a trend in sociopolitical thought and theory as nationalism offers a different vision – it is natural to go down in history by taking part in the struggle of nations for self-identification. For world history is interpreted as history of the making and the development of nations. But, naturally, most attention in this case is paid to national history. It is presented as movement of a nation from self-identification, through national mobilization, and, finally, to the formation of a state, in which the nation will have every possibility to develop through gaining full authority.

This type of historical narrative is so widespread in present-day Ukraine that it may turn out to be the only possible one or at least the only effective one in overcoming the Soviet totalitarian legacy and reforming the country. It is from this angle that the 1917-21 Ukrainian Revolution is most often viewed. The struggle of two – nationalist and Bolshevik – projects for domination in Ukraine is most often defined as the linchpin and the main intrigue of the event. The Ukrainian Revolution is being recognized as a separate historical event, a revolution proper, through emphasizing its national character. Even a tradition was established to use the term “1917-21 Ukrainian Revolution,” although it is not yet in general use.

This contraposition hides the important particularity of that time’s events, namely, the establishment of a liberal worldview, above all, the values of the individual, his or her rights and freedoms, and the rule-of-law state that ensures them.

LIBERAL WORLDVIEW IS THE PREROGATIVE OF ELITES

This calls to mind the stratification of the Maidan – liberal and nationalist-oriented. Both of these components of the protest movement defended the freedom and independence of Ukraine, but each proceeded from its own motives. And it is extremely wrong to reduce the motives of liberals to the considerations of national self-assertion.

We in Ukraine really have some problems of historical nature, as far as upholding the liberal tradition is concerned, even though present-day Ukraine is developing as, above all, a country of liberal orientation. The vast majority of Ukrainian citizens show preference to parties with clear programs. Support for nationalist parties and left-wing movement defies comparison with support for liberals or centrists.

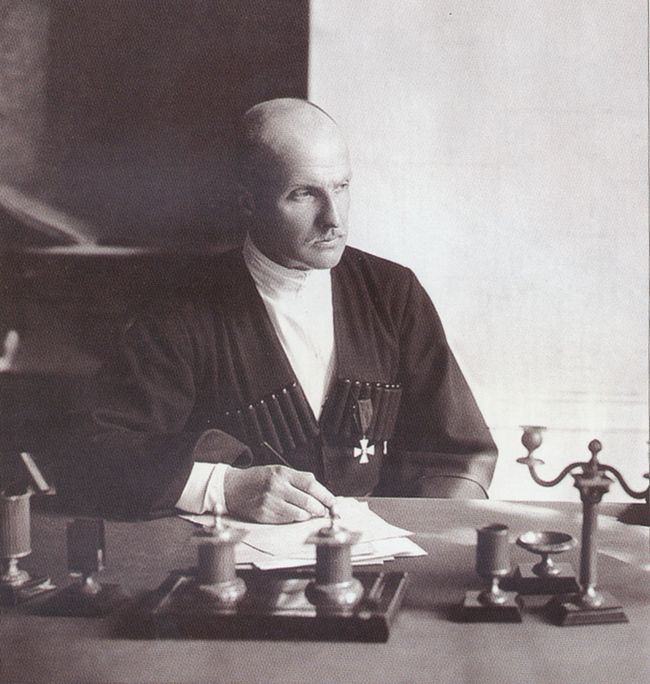

HETMAN PAVLO SKOROPADSKY IN HIS OFFICE ROOM. KYIV, 1918

Nevertheless, Ukrainians seem to be deprived of the history of a dedicated formation of a democratic rule-of-law state that puts emphasis on the interests of the individual, not of the group.

The awareness of this allows one to better understand the problems of Ukraine’s integration into the liberal world. And we can see the problems of this integration at all levels – from individual to geopolitical. For this also complicates the integration of Ukraine into Europe.

Ukraine has really had not much of liberal history. The archaic Russian Empire did not recognize personal freedoms and the rights of nations for the most part of its existence. Western Ukrainians were a bit luckier, for they at least had the basic rights proclaimed in the Habsburgs’ empire constitutions of 1848 and 1867. Reproducing the Russian imperial trends, the Soviet Union viewed man as a cog in the state mechanism and only formally declared the right of nations. But Ukraine established the tradition of building a democratic state not in 1991, when it gained independence. The Ukrainian Revolution put forward a liberal project, albeit on very short distance. It was basically the project of Pavlo Skoropadsky’s Hetmanate.

By force of historical tradition, it is the elites, rather than the broad masses, that were bearers of liberal values in Ukraine. History proves this. It is no accident that the author of the first Ukrainian constitution was Pylyp Orlyk, representative of a noble family, a hetman. Sergey Muraviov-Apostol, the descendant of a hetman’s clan, propagated the idea of democratic transformations among the Decembrists. Taras Shevchenko drew support from descendants of the Ukrainian nobility, such as, for example, the Lyzohub brothers. Not least because of this support, he realized himself as a thinker, poet, and artist.

Liberal aspirations were more inherent in the nobility than in the grassroots. For example, Shevchenko’s passionate appeals to peasants sometimes prompted them to turn him in to the police. The official ideology of obedience and feudal paternalism was deeply rooted in ordinary people. The Orthodox Church also contributed to this.

And although Ukrainians remained freedom-loving people, it is wrong to see rebellious manifestations as premises of liberal consciousness. Revolts and uprisings, such as Koliivshchyna, were a short-time comeback of the archaic military democracy. They emerged spontaneously and were usually “feasts of disobedience.” They could not put forward any positive programs of human cohabitation. In any case, they showed no respect for law or personal freedom.

The tradition of the formation of liberalism is inseparable from the formation of such values as rights and freedoms of the individual. Therefore, its genesis should be sought not in spontaneous peasant or Cossack movements but in noble salons and associations. Throughout the 19th century, liberal democratic persuasions became widespread among the nobility, which was a challenge to the deathly environment of great power chauvinism and conservatism.

This rather paradoxical tendency was caused by certain factors. Only people of noble origin had access to education in the Russian Empire. Therefore, only they had enough erudition and intellect to get acquainted with progressive political ideas and grasp the prospects of building a rule-of-law society, no matter how difficult it is. What also mattered was the possibility of traveling abroad and comparing the results of the development of the Western civilization and Russia.

The conclusions were not in favor of Russia. The advantages of the West were recognized by both the technocrats, who emphasized the economic effectiveness of the Western model, and the humanitarians, for whom the humane anthropocentric nature of liberal institutions was a convincing argument. The essential link between the two dimensions was later substantiated in liberal theory.

Ukraine has changed very much in the past 100 years. Like the whole world, it has turned from a predominantly rural into an urbanized country. The urban way of life has promoted scholarship, rationalism, and tolerance to different things.

While nobles were the only bearers of liberal democratic political orientations until the 19th century, now it is the middle class, big city intellectuals, and representatives of the creative class that follow these orientations.

By the way of life and mental outlook, these strata can be likened to the nobility. It is the noble culture that these strata feel organic affinity with. They are in fact its direct descendants. This particularly concerns political culture and is expressed in the advantage of liberal orientations.

FATAL POPULISM OF THE UKRAINIAN REVOLUTION

But, as the 19th century drew to a close, representatives of the “third estate” took over the initiative of forming the political agenda from the nobility. This agenda noticeably shifted to the left: the slogans of social justice upstaged those of people’s equality before the law. The old elites got the vote of no confidence. This applied to conservatives and noble liberals almost by equal measure.

Almost at the same time, nationalism was born as a trend in sociopolitical theory and practice. Like the social democratic trend, it appealed to the masses and was trying, for this reason, to do without too complicated interpretations. Yet it took a favorable attitude to national elites in certain contexts.

Oddly enough, both of the conflicting concepts – communist Bolshevism and nationalism – turned out to be quite similar. The two concepts propagated supremacy of the group over the individual. In real historical events, this led to inhumane actions, when the life of people was sacrificed in order to realize political ideals.

HETMAN PAVLO SKOROPADSKY REVIEWS A PARADE OF THE 1st UKRAINIAN COSSACK RIFLE (GRAY COAT) DIVISION. SEPTEMBER 1, 1918

The conservative political philosopher Viacheslav Lypynsky once noted this similarity. His sagacity was surprising, for he had written his policy works well before the totalitarian regimes took the heaviest human toll under the slogans of these ideologies.

But these ideologies proved to be rather popular at the turn of the 20th century in Ukraine, where class oppression was accompanied by ethnic oppression. Critically short of land, the Ukrainian peasantry was deprived of the elementary conditions of survival. The Ukrainian intelligentsia was more acutely aware of ethnic oppression, as it was unable to form a Ukrainian humanitarian space. Accordingly, the solution of the nationalities question usually depended on socializing innovations and vice versa.

Ukrainian intellectuals took part in the revolutionary movement from the spring of 1917 onwards under the slogans of winning the rights and freedoms. Left-wing rhetoric was much in demand. This sometimes led to amusing incidents. Socialists-Federalists, a moderate Ukrainian liberal democratic party, had the component “social” in its name only to meet societal demand.

As societal sentiments were radicalized, populism proved to be the most effective political strategy. Promises catapulted to the highest rungs of political hierarchy the people who were unable to keep these promises – also because the expectations they caused were overrated. Yevhen Konovalets critically appraised this tendency, summing up the consequences of the Ukrainian Revolution: “It is the greatest glory for every nation when as many names as possible are written on the tablet of its heroes. But still one must see to it that there are not too many of them in comparison with the consequences of their heroic work, in comparison with the achievements of the whole nation.”

Throughout 1917, the life in Ukraine became chaotic – the economic system was disintegrating, the country was full of armed frontline deserters, and peasants were dividing land. The Bolsheviks spread propaganda in Ukraine and launched direct military operations against the UNR in December 1917. But, instead of establishing a new life and organizing defense, the parties represented in the Central Rada wasted time in the never-ending inter-party disputes.

Some Central Rada members, such as Yevhen Chykalenko and Dmytro Doroshenko, saw that the policy of populism had no prospects. Representatives of Ukraine’s allies Germany and Austria-Hungary also expressed dissatisfaction over the UNR’s failure to meet its allied commitments. Finally, the collapse of the UNR government made it possible to stage the coup that brought Pavlo Skoropadsky to power.

THE HETMANATE: ACHIEVEMENTS AND MISTAKES

Skoropadsky declared an intention to build a democratic Ukrainian state, in which liberal freedoms will be observed and the main socioeconomic contradictions will be resolved by way of gradual reformation. At the same time, the Ukrainian State was supposed to implement the national political ideal, ensuring the development of Ukrainian culture and uniting the territories populated by Ukrainians.

As for UNR figures, they usually cherished socialist ideals which they were going to implement by way of revolution and suppression of the rights of the well-to-do. As part of this suppression, it was intended to encourage the division of landlords’ lands and to resort to requisitions, which reinforced the right to own private property. The UNR Directory also announced the “work principle” which meant political incapacitation of the “non-working” strata of the population.

This was further complicated by international problems. UNR leaders always emphasized the equality of peoples, but in reality there occurred unfortunate and sometimes horrible excesses of xenophobia, above all, anti-Semitism. Even with due account of the positive intentions of UNR leaders, the blame for these excesses also lies, to a certain extent, on them. For they failed to ensure governance in the country they revolutionized, stop the otamans’ arbitrary rule, and adequately punish the guilty.

The idea of recognizing today’s Ukraine as successor of the UNR seems to be rather problematic at least because of the socialistic guidelines of the latter. Sometimes we really reproduce the UNR matrix – in the fruitless disputes of parliamentary parties, in the populism of politicians, in territorial disorganization, in the vain hopes for self-organization which results in disorder and lawlessness. But do we like it? Did we imagine Ukrainian independence like this?

By choosing the narrative of the past, we choose the future. For this reason, today’s Ukraine must be pronounced the successor of Skoropadsky’s Ukrainian state. Let us have a look at just the main results Skoropadsky managed to achieve in the short time of being the Ukrainian State leader.

His government built a vertical of power, organized the work of ministries, introduced the institution of civil service, established law and order, and reformed zemstvos – which allowed the state to pursue its policies on the territory of Ukraine in an actual, not declarative, way.

On the top of the vertical chain of command was the Hetman as a personification of the old Cossack political tradition. Skoropadsky met the requirements of this tradition, for he belonged to an old hetmanite clan, to the military top. But his authority, as he himself noted, was temporary and not monarchic – until the political and economic life was put in proper order. Then it was planned to convene a constituent assembly (Soim) which would determine in a democratic manner the next form of government in the Ukrainian State.

The Hetmanate existed within broad boundaries, embracing in the north and the east some territories that now belong to Belarus and Russia. The government’s active foreign policy was aimed at further expansion of these borders. A tentative agreement was reached on the annexation of Crimea. The Ukrainian State received wide international recognition. In particular, Bolshevik Russia also recognized it.

An independent judicial system was being established under the auspices of the State Senate. This means that the Ukrainian State was assuming the signs of a rule-of-law state, and revolutionary lawlessness was giving way to justice, particularly in the provinces. The basic liberal freedoms, such as rights of the political opposition and freedom of the press (with a few exceptions because of political instability) were not only declared, but also secured.

The economy was noticeably revitalized, above all, thanks to a sober economic and financial policy and the cancellation of the previous government’s socialistic initiatives. The government began to carry out agrarian reform in order to create a strong middle class of farmers and give up large-scale land ownership.

Ukrainian education also received a major impetus: two universities and a lot of schools were opened, curriculums were revised, and teacher-training was streamlined. Ukrainian schoolbooks were published in large circulations and personal scholarships were introduced. The National Library and the Ukrainian Academy of Sciences – the institutions that promoted the country’s independent intellectual development – were founded.

The government cared about the development of Ukrainian culture, allocating considerable funds to support theaters, music, museums, and cultural figures. The Ukrainian State effectively supported Ukrainian communities outside the drawn borders, earmarking funds for cultural development and the Ukrainian press.

These results became possible because Skoropadsky adhered to the principle of professional (not party-related) fitness in job placements. He looked for professional executives anywhere. But Ukrainian circles could not offer many of them – most candidates lacked managerial experience and many – even basic education. So, he had to recruit non-Ukrainians, people who had received experience in the managerial structures of tsarist Russia.

Incidentally, inviting foreign specialists is now a common practice. This step is in fact considered unavoidable when modernization is the goal. But rich and successful countries also resort to this practice to revitalize the economy and increase intellectual vigor. This only increases the value of intellect in the liberal world of today.

Skoropadsky’s job-placement policy would be called technocratic now. But at that time it was branded as anti-Ukrainian by those for whom competence and experience did not constitute such a value as rhetoric dexterity. In other words, the intellectophobic tendency prevailed in Ukraine at the time.

The Hetmanate emerged as a reaction to UNR leaders’ inability to take control of the situation and was eventually overthrown by the same UNR leaders. They considered Skoropadsky No. 1 enemy to themselves. As for Skoropadsky, he hoped to the last minute that the ideal of statehood would outweigh personal ambitions. He was mistaken. He was also mistaken in viewing the White Movement as a prospective ally of the Ukrainian State. He himself admitted this mistake later.

He was not mistaken in the main thing – in defining Russian Bolsheviks as No. 1 enemy to Ukraine. Agreeing to Skoropadsky in this, we have to admit that his state-formation project was the most effective attempt to resist Bolshevik expansionism in those turbulent years.

RESTORING THE LINK OF TIMES

The Hetmanate was the embodied antipode of Bolshevik imperial totalitarianism. It put elitism and technocratic principle of personnel selection against populist Bolshevism. Imperial principles disguised as internationalism received an answer from moderate nationalism. After all, the Hetmanate was a liberal project to counterbalance Bolshevik totalitarianism. This is why they branded it so much, distorting historical memory about those by no means worst six months of Ukrainian history.

Memory keeps historical events selectively. We perceive historical subjects in the measure to which we can embed them in our own worldview, our own experience.

This is why the creative class and the urban intelligentsia have their own historical memory. This memory perceives the world history of liberalization as its own – whether it is about the French revolution or the emancipation movements of the 1960s. It is difficult for it to find food in Ukrainian history.

Unfortunately, historians in present-day Ukraine usually meet the demand for national history. Hence, those who do not abide by the nationalist ideology are doomed to be excommunicated from Ukrainian history. National historians almost do not care about them.

It seems that Hamlet meant this very situation, when he said that “the time is out of joint.” Indeed, we can see the interrupted link of time. The values we cherish seem to have arisen from nowhere. So Russian propaganda may be true to say that the ideas of the rights and dignity of man is a heresy borrowed from Europe, and nationalism is the only organic concept for Ukrainians.

But our history also comprises arguments to deny this statement. It is enough to take a closer look and give credit to those who deserve it.

Erecting a monument to Pavlo Skoropadsky in Kyiv could be such a gesture of gratitude. It would at least testify to the recognition of the liberal tradition and elitism as prerequisites that influenced the course of Ukrainian history.

We would like to see this monument, naturally, on Pechersk Lypky, for Skoropadsky chose this place for his residency – it was the epicenter of decision-making in the Ukrainian state. But there is also another reason. The monument would remind the Ukrainian political class of what kind of Ukrainian political forces we would like to see – educated, patriotic, and competent. What is more, we expect them to sincerely cherish the values of rights and freedoms and build a rule-of-law Ukrainian state.